This article reproduced with kind permission from The Railway & Canal Historical Society.

Click the blue journal cover image to access the full journal directly from their archive.

Introduction

The story of the Barry Railway has usually been told stressing two phases: the period of struggle as the promoters of the enterprise fought for two years to obtain parliamentary authorisation, finally securing this in August 1884; and the period of reward when those who had fought the 1882-1884 struggle were able to enjoy the benefits of the completed dock and railway.[1] For those of the company’s backers who were Glamorganshire colliery proprietors or exporters/shippers of that coal, these rewards were partly in the form of good-value-for-money services enjoyed as customers of the enterprise. But the direct rewards to Barry shareholders were substantial also. In February 1890 the first dividend on the company’s ordinary shares was declared, at 2.75 per cent for the half-year to 31 December 1889 (or 5.5 per cent per year). Six months later the rate declared rose to 5 per cent (or 10 per cent p.a.). From October 1890 onwards London Stock Exchange prices for Barry ordinary shares regularly exceeded double the par value of the shares.[2] W.J. Stevens’ 1902 manual for investors in British railways stated: “The Barry has been a wonderfully successful company, having paid large dividends right from the beginning of its career, and its Ordinary stock enjoys the distinction of being quoted the highest of any Home Railway Ordinary stock.”[3] In the words of Hamilton Ellis, “the Barry Railway proved to be something of a goldmine, as railways went.”[4]

The path from parliamentary authorisation in August 1884 to the commencement of ten per cent per year dividend declarations six years later was not all plain-sailing for the Barry Railway, however. Certain financial “teething troubles” were encountered which became increasingly pressing during late 1886 and early 1887. One symptom of these problems was the price at which the company’s partly-paid shares were trading in Cardiff[5] (authorisation for trading on the London Stock Exchange was not given until October 1889). In late 1886, the £10 ordinary shares were £6 paid, with notice given in October to shareholders to pay a further £1 by 15 January 1887, and a further £1 by 20 February 1887. These shares were trading at £3.75, a discount of £2.25 on the £6 that original subscribers to the company had by that stage paid for the shares.[6] Resolution of these early financial stresses was not achieved overnight. As late as 27 August 1889, the Financial Times was warning its readers that “the prospect for the [Barry] shareholders is not so bright … it is doubtful whether the preference shareholders will be paid in full or even partially for some time to come.”[7] Where a company’s preference shareholders cannot be paid in full, that means the ordinary shareholders are receiving no dividend. So this Financial Times warning has to be read as a warning that Barry ordinary shareholders could expect to receive no dividends whatsoever for “some time to come.”

The financial “teething troubles” encountered by the Barry Company during the latter part of 1886 and early 1887 were thus far from trivial, and they took some time to be overcome. Robert William Perks, an outsider to South Wales who had played no part in the establishment of the Barry company, played a significant role in the enterprise’s passage from its financial difficulties of 1886-1887 through to its status as “something of a goldmine, as railways went.” The aim of this paper is to give an account of this hitherto unwritten chapter in the history of the Barry Railway. As well as contributing to a better understanding of the business history of the Barry enterprise, this provides a building-block towards an improved understanding of the overall business career of R.W. Perks.

Among transport historians, R.W. Perks’ name is probably best known for his activities in the development of urban passenger railways in London. Having qualified as a solicitor in 1875, Perks was principal legal adviser to the Metropolitan Railway through a fifteen year period that concluded in June 1895. In September 1901, Perks was elected a director of the Metropolitan District Railway (MDR) and immediately replaced James Staats Forbes as chairman. Perks was MDR chairman until February 1905, and continued as deputy chairman until July 1907. During that period Perks oversaw the conversion of the MDR from steam to electric traction, and the integration of the MDR into the broader Underground Electric Railways of London (UERL) ‘combine’, created by Charles Tyson Yerkes. For those familiar with Perks’ name from these ‘London Underground’ roles, it may come as a surprise that his first directorship of a railway company preceded his MDR board position by over fourteen years and was with the Barry Railway ─ an enterprise focussed much more on moving coal than on moving people.[8]

This paper consists of three main sections. The first examines the nature and causes of the financial challenges facing the Barry company in late-1886/early-1887. The second examines the decisions made within the company to respond to those challenges, and the role played by R.W. Perks in the response process. The third section examines the circumstances surrounding Perks’ resignation from the Barry board in late July 1890, and the continuing interactions he had with the enterprise and its board members through to 1892. These three main sections are followed by a ‘summary and conclusions’ section which attempts to draw together the main threads from the body of the paper.

I The Barry Company’s position in March 1887

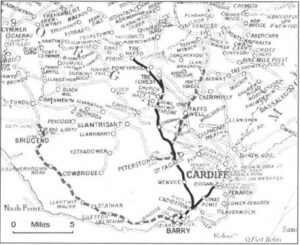

The Barry company was conceived of as an integrated dock and railway enterprise to provide a more streamlined and cost-effective alternative for the shipping of coal from the Rhondda (and nearby) collieries than the services available via the Taff Vale Railway (TVR) and the docks in Cardiff owned by the Marquis of Bute. Prior to being simplified to “The Barry Railway” in August 1891, the official name of the company was “The Barry Dock and Railways Company”. While the roots of the project can be traced to earlier years, the real impetus came at the start of the 1880s with booming demand for South Wales steam coal, growing congestion problems on the Bute docks in Cardiff, and an increasingly explicit unwillingness by the Marquis to commit to extending and upgrading the facilities ─ either through significant additional investment himself or through restructuring the ownership to allow for new “outside” investment. The reluctance of Bute to increase his own investment stake in the docks is understandable: the capital already tied-up in them had not generated particularly attractive returns to the Marquis; and there were fears among his trustees that the

South Wales coal boom would not last.[9] Nevertheless the severity of the congestion problems at Bute docks during 1880 to 1882 was imposing substantial losses on the Rhondda colliery owners and the shippers of the coal.

Daunton describes two ways in which these losses were generated:

The first was through delays at the docks disrupting railway traffic. Collieries loaded direct into wagons so that they were frequently forced to stop production by the detention of wagons at the docks, while the increase in the time taken to make a round trip meant that more wagons had to be hired. … The second source of loss was through delays to shipping. Almost half the ships were kept waiting outside the docks at a cost estimated conservatively at £50,000 a year … once inside the dock, it could take 16 hours to reach the berth, and pressure on the railways meant delays in the arrival of cargo which further increased the time it took ships to turn around.[10]

On top of these two types of costs arising directly from the acute congestion on the Taff Vale Railway/Bute Dock infrastructure, two further types of cost should be added. The very high dividends paid by the Taff Vale Railway during this period, together with the steep reductions it made in its freight charges later in the decade, seem to suggest the TVR was using the congestion on the infrastructure as an opportunity to charge monopoly prices.[11] And the various direct effects of the congestion acted as a deterrent to the opening up of additional colliery facilities, and the pursuit of additional coal export contracts, leading to further forgone revenues for the colliery owners and coal shippers.

The Barry enterprise that received parliamentary authorisation in August 1884 was for the construction of a new dock between Barry island and the mainland of Wales, 7 miles south-west from Cardiff, together with 23 miles of railway to provide connections to this new dock. This compact railway system comprised a main line and four short branches. The route of the main line was from the Dock towards Cardiff for about 1¾ miles, then turning north at Cadoxton for 15½ miles to Pontypridd where the Rhondda flows into the river Taff, and on up the valley of the Rhondda for 1¾ miles to Trehafod and a junction with the Rhondda branch of the TVR. The four branches, none greater than 2 miles in length were to provide for two more connections from the TVR system into the northern part of the Barry main line (although one of these was never built) plus two connections with the Great Western Railway almost directly west of Cardiff. While that might not sound like a large quantity of railway, the terrain, combined with a desire to minimise the gradients for loaded coal trains to climb, made for some costly engineering work, including two tunnels, one near Pontypridd (1,373 yards long), and one about a third longer somewhat south from the GWR connector-branches.[12]

This system of railways authorised in the 1884 Barry Act was rather more “compact” than the company’s promoters had desired, having shed two segments contained in the original proposal put before the 1883 session of parliament, but defeated in the House of Lords committee stage. One, a proposed branch from the main line at Cadoxton into Cardiff was largely restored in the Barry’s 1885 Act. The other was a permanent, and more concerning casualty. In the original proposal, the Barry’s main line was to go on from Ponypridd for 8 miles further up the Rhondda valley, essentially parallel with the TVR, so as to provide direct service to the group of collieries owned by David Davies and Co. David Davies was one of the “prime-movers” among the promoters of the Barry, as will be discussed further below, and his colliery enterprise was by this stage the second biggest coal producer in South Wales with an 1883 output level of 1.25 million tons.[13] With the Barry’s main line stopped short at Trehafod, this meant that here, as throughout the rest of the Barry system, the company was dependent on other railways to convey coal from the producing collieries to a point of access to the Barry’s own rails. Particularly where such feeder services would be via the TVR, this clearly posed a significant business risk to the Barry enterprise ─ namely of the TVR seeking to set charges that would “deter” customers from using the Barry system and “encourage” them to view the TVR/Bute-docks alternative as preferable. Thus when the Times “State of Trade” column reported the passage of the 1884 Barry Act, it sounded a note of caution:

… the passage of the Barry Dock Bill is the event of the week. Opinions differ as to the effect upon the scheme of the reservation of railway facilities, some authorities going so far as to say that the failure to obtain the railway is fatal to the success of the undertaking.[14]

The promoters of the Barry appear to have been more sanguine. The buoyant demand for South Wales steam coal during 1881 and 1882 had continued through 1883 and 1884. The average pithead price for Glamorgan coal rose from 5.83 shillings per ton for 1882 to 6.23 for 1883 and 6.25 for 1884. Congestion problems on the TVR/Bute docks infrastructure had not abated while the struggle for parliamentary authorisation of the Barry scheme had been in progress ─ a struggle in which the TVR interests and the Bute interests were at the forefront of the resistance against the Barry scheme.[15] And the Barry promoters would have been aware that the British system of law for railways provided for legal remedies against predatory pricing. Where would-be victims of such practices could feel confident that they had sufficiently deep pockets, patience and strength of will to see through the required processes, it was probably reasonable for them to discount this particular business risk. And in this case it was probably reasonable to expect that the new enterprise would enjoy the goodwill of a sufficient number of colliery proprietors and coal shipping customers who would stand by it until any necessary legal remedies had been put in place. In the event, the Barry company did succeed during 1888 in securing solid protections against predatory pricing on freight conveyed into its system, and thus this was achieved with good lead-time before the system’s opening in 1889.[16] Nevertheless perceptions regarding this type of business risk no doubt affected the willingness of at least some potential investors to commit share capital into the Barry enterprise during the period prior to the 1888 clarification of this situation.

Once the 1884 Barry Act had been secured, the Barry’s promoters moved rapidly towards commencing the work of building the new transport enterprise. The first meeting of the Barry board was held on 4 September 1884 and a second meeting followed on 19 September. At these two meetings, a total of 51,488 of the company’s ordinary shares were allotted, legally committing the allottees to paying £10 into the company for each share through a sequence of calls to be announced by the directors as the money became needed. This secured almost half of the £1.05 million of ordinary share capital the 1884 Barry Act had authorised. The subscribers of this segment of the company’s investment-funding requirements were people who had already signalled their support for the enterprise during the battle for parliamentary authorisation: i.e. the promoters of the enterprise and their associates and friends. At this stage there had been no public offer. About four fifths of this first half million pounds worth of commitment to provide funds appears to have come from the thirteen original directors of the company.[17]

At these September 1884 meetings the Barry board resolved to issue a prospectus making an offer to outside members of the public to subscribe to a further £100,000 of the company’s ordinary shares. And a call for tenders to construct the Barry dock was approved. The parliamentary estimates for the company’s costs had £561,993 for the dock, £722,123 for the railways and £9,954 for roads.[18] The Barry board’s thinking appears to have been that since constructing the dock would be the most time-consuming element of the overall infrastructure-building task, step one for the company should be to lock-in enough capital funding to cover the work on the dock, and get that work under way. The call for tenders re. construction of the dock was advertised on 26 September.[19] The Barry prospectus was published on 1 October (subscriptions to close at noon 13 October), and stated “It is expected that the dock and railways will be opened for traffic in 3½ to 4 years.”[20] This signalled to would-be subscribers that the earliest any commencement of dividend payments on the shares might be expected would be late in 1888.

This public offer of shares in the Barry company was not a success. On October 15, 1884, the Barry directors considered the applications received and were able to allot less than 3,000 of the 10,000 shares which had been offered. The board minutes report that the directors agreed “to take up among themselves proportionately the number of shares sufficient to make the total capital subscribed amount to £600,000.”[21] Although allowing it to be asserted that the company’s public share offer had been success, this left the Barry enterprise heavily dependent on a very small group of shareholders to provide the major part of the money required for the dock and railway construction program. This dependency was accentuated by a further decision made at the same board meeting. With £600,000 of the company’s ordinary shares now allotted, there remained £450,000 authorised to be issued but thus far unspoken for. The board resolved “that David Davies would subscribe for a further £150,000 of shares, Mr Crawshay Bailey the same, and that the balance be subscribed by the other directors present proportionately.”[22] It is not clear from the board minutes what the arrangements were intended to be for this £450,000 tranche of shares. They definitely were not subject to the same calls as were made on the shares in the larger tranche. Indeed no money seems to have been paid-up on the shares in this £450,000 tranche prior to their being cancelled two and a half years later, as discussed further below. It is possible that what the subscribers were committing themselves to was more along the lines of an under-writing arrangement. That is, if other investors willing to take up these shares had not been found by the time the company came to need the funds, and the shares allotted into their names accordingly, then the 15 October 1884 “subscribers” would be required to come up with the money. In the meantime the Barry company was able to report that £1,050,000 of capital has been issued in ordinary shares of £10,[23] providing comfort to those making loans to the company, and trade creditors etc.

The ceremonial “cutting the first sod” for the construction works of the Barry company was held on 14 November 1884. At that point the “economic fundamentals” of the Barry enterprise can be summarised as follows. The company was about to embark on constructing a transport infrastructure system that would take at least 3½ years to complete and which would require about £1.3 million of capital funding, provided capital spending could be contained within Parliamentary estimates. The company was authorised to raise £1.4 million of capital to do this (£1.05 million in share capital plus 0.35 million in borrowings), but the “margin for comfort” was much narrower than the £100,000 this might seem to imply. The parliamentary struggles of 1883 and 1884 had cost the Barry promoters a combined total of £70,000, and the 1884 Barry Act authorised all of that cost to be covered out of the company’s funds.[24] And various other miscellaneous non-construction costs existed that would need to be met during the course of the period before any revenue-earnings could be expected. The enterprise was dependent on just 13 men (the company’s own directors) to provide it with over 60 per cent of the £1.4 million of capital ─ unless the shareholder base of the Barry company could be successfully broadened. The 25 per cent of the £1.4 million authorised to be raised in borrowings might become difficult to obtain from “outsiders” on reasonable terms, if there were to emerge question marks over the projected profit/loss arithmetic of the Barry company or regarding the likelihood that the calling-up of the company’s share capital might not proceed smoothly as the funds came to be needed. Finally, the nature of the Barry project’s compact railway system integrated with the new dock meant that virtually all the capital-spending would need to have been completed before any serious revenue-earning could commence. Any delays in completing the dock, in particular, would extend the period in which the capital invested in the enterprise was generating no return.

Changes in the company’s financial situation

The story of the Barry enterprise’s finances from project commencement in late 1884 to the tensions of late 1886/early 1887 is essentially two stories: how the capital funding required for the construction work came to increase; and how the ability among the small core of controlling Barry shareholders to furnish share capital in the quantities required, came to diminish.

The overall construction task for the facilities authorised by the 1884 Barry Act was split into four contracts. Contract one was for the dock and the railways in and close to the dock area, with contracts two to four covering the railway system as such. The southern segment up to and including the GWR connections was contract two, which thus included the longer of the two tunnels required (Wenvoe). The northernmost segment, including the Treforest tunnel was contract four. The engineer with responsibility for supervising the work on contract four was James W. Szlumper, who had worked with David Davies on railway-building projects in Wales in the 1860s.[25] John Wolfe Barry had responsibility for supervising the work on the remainder of the railway system and the dock. With his partner H.M. Brunel (the son of Isambard Kingdom Brunel) and T. Forster Brown of Cardiff, it was Wolfe Barry who had drawn up the plans for the Barry scheme used by the promoters in the 1882-84 parliamentary processes.[26]

As noted earlier, tenders for contract one were advertised for in September 1884. Those lodged were opened at the Barry board meeting of 15 October 1884. One of the ten was very low, below £330,000, and two very high with the highest just under £930,000. The remaining seven ranged from John Jackson’s £497,684 1s 8d to £641,881. Wolfe Barry recommended that the John Jackson tender be accepted and the directors agreed to that.[27] But shortly afterwards Jackson informed the Barry directors that he had made a mistake in the preparation of his tender and sought permission to “amend” it by adding £48,000. Jackson was asked to attend the Barry board meeting of 28 October and provide an explanation. After hearing Jackson, and then asking him to withdraw and await their decision, the Barry board unanimously resolved that David Davies and Wolfe Barry should go and meet with T.A. Walker, who had submitted the fourth lowest tender (and the only “round-number” one, at £600,000 exactly) “to ascertain from him if he was disposed to amend his tender and if so for what amount.” As Walker was known to be in Cardiff that day, this meeting was arranged post haste, with the board to reconvene upon the return of Davies and Wolfe Barry ─ and Jackson kept waiting in the meantime.[28]

In October 1884, John Jackson was aged 33 and a relatively inexperienced public works contractor, although his work on the Tower Bridge was soon to make his name much better known.[29] Walker, in contrast was 56, highly experienced and very well-regarded professionally. He had been hand-picked by Sir John Hawkshaw in 1879 to work with him on rescuing the Severn Tunnel project for the GWR. This occurred two years after Walker’s £948,959 tender for the project had been turned down by the GWR as too expensive.[30] In October 1882 Walker had won the contract to complete the “Inner Circle” for the two London underground railway companies. The engineer supervising the work on that project was Wolfe Barry, who had started his engineering career as a pupil and then assistant of Sir John Hawkshaw.[31] The “Inner Circle” project was completed in September 1884.[32] Although Walker’s enterprise still faced a good deal of work on the Seven Tunnel project, the fact that he had just successfully completed another major project would probably have boosted the confidence of the Barry directors that the Walker firm would have the capacity to take on the construction of their dock. And in the middle of October 1884, there came a further boost to Walker’s public standing when it was reported that the two headings beneath the Severn had been joined and the GWR chairman Daniel Gooch had “traversed” the full length of the tunnel.[33]

When the Barry board meeting reconvened on 28 October 1884, David Davies and Wolfe Barry reported that Walker was willing to reduce his tender to £563,907.10s. The board resolved to accept this tender, proceeded to complete the remainder of the day’s business, and then recalled Jackson to inform him that Walker had reduced his tender “to the satisfaction of the board, and that they had accepted the same.”[34] Two points on the arithmetic are worth noting at this point. The revised Walker tender that was accepted was £18,223 above the revised Jackson tender that was rejected. The Barry directors appear to have made a conscious decision to put the benefits from Walker’s established reputation for high quality work and “getting a job done”, and from the public confidence effects of enlisting Walker’s name, ahead of that further addition to the project’s up-front costing. Secondly this resolution of the dock tender process took the company’s accepted cost figure for constructing the dock above the figure in the parliamentary estimates (£561,993). On top of this, there came a potential downside to embracing Walker’s high standards of quality and seeking to co-opt his public good repute. If at some stage in the future the Barry board might want to switch course and try to cut corners on engineering quality in order to economise on capital costs, the directors would now need to consider the consequences to the company of Walker taking a stand to resist that. Thus October 28, 1884 can be regarded as a day on which the Barry board both accepted an escalation in the enterprise’s projected capital costs, and restricted their own scope for future freedom of manoeuvre.

A much more significant cost-side shock to the Barry project emerged eight months later, when Walker had succeeded in completing the dams needed to close out tidal water from the area to be the dock site.[35] The plans for the Barry project put before parliament in the Bills of 1883 and 1884 were for a dock of 40 acres, and the parliamentary costings and approvals for capital-raising were based on that concept of a 40 acre dock. The Barry prospectus inviting the public to subscribe for shares in the company stated “The area of the dock will be 40 acres.”[36] But it was not until the contractor’s dams has been completed and tidal water excluded from the area within those dams that proper drillings could be made, to establish “the exact nature of the strata underlying the dock, which had already been found to be disturbed by faults.”[37] Once these drillings became possible, and were carried out, it became evident that the planned location of the southern wall of the projected dock was non-viable, because along that line there was “a great depth of soft material.”[38]

Wolfe Barry’s response to this problem was to recommend that the south wall of the dock be built further to the south, on firmer foundations, and that the area of the dock be thus expanded to 73 acres. Wolfe Barry put these revised plans before the Barry board at its meeting of 16 October 1885. The directors discussed the proposed alterations at both this and their next meeting, but probably had little alternative but to agree.[39] Clearly this would require some rewriting of what the company required under contract one, and a further negotiation with Walker on the cost. The latter may have been impeded by the fact that Walker was away in Argentina. He had left England on 7 September 1885 and did not return until 14 December1885. On 2 September Walker had entered into a contrast worth about £4 million to construct a new system of docks in Buenos Aires, with Sir John Hawkshaw as engineer. This visit was to enable Walker to make arrangements for work on that project to commence.[40]

These decisions by the Barry directors to accept a scaling-up in the size of the dock from 40 acres to 73 acres could be expected to have a longer term upside, in terms of increasing the revenue-earning capacity of the facilities, once in operation (and assuming a sufficient buoyancy of demand for the Barry facilities). But the more immediate downside effects in terms of the company’s investment funding needs were substantial. The redesign meant delays in the time to completion, with time taken up for the replanning process and the board’s decision-making re the new plans, and additional time possibly needed because of the now larger construction task. Walker wrote to the Barry board about these timing matters on 4 January 1886, and on 15 January the directors agreed to authorise Wolfe-Barry to extend the completion date for contract one. In cash terms the impact appears to have been to increase the expected cost to the company of contract one to £712,300 ─ almost £150,000 more than the figure accepted in October 1884.[41]

The principal shareholders

Turning now from developments affecting the Barry enterprise’s need for investment funds to developments impacting on the ability of the company’s small core of controlling shareholders to furnish such funds themselves, it is useful to begin by noting who those controlling shareholders were. Two of the thirteen original directors were landowners (Lord Windsor and Crawshay Bailey) and three formed a ‘bloc’ comprising David Davies and two of the major partners in his colliery enterprises (David Cooper Scott and John Osborne Riches). When Riches died in 1886, he was replaced on the board by Davies’ son Edward. The remaining eight were either proprietors of significant South Wales colliery enterprises operating independently from the David Davies concerns (Lewis Davis, Archibald Hood, John Howard Thomas); or shipowners/coal-exporters (Thomas Roe Thompson and John Fry); or both of the above (John Cory, James Walter Insole and Edmund Hannay Watts). The enterprise controlled by Lewis Davis (1829-1888) was almost certainly the second biggest coal producer represented on the Barry board. The biographers of David Davies paint a picture in which Lewis Davis is almost as important in the promotion of the Barry enterprise as David Davies (see Ivor Thomas, op. cit., pp. 289-290). The 1899 biographer of Lewis Davis put it differently referring to: “Mr Lewis Davis as leader, supported by David Davies, Llandinam, and other prominent colliery proprietors …”[42]

Lord Windsor, the Barry company’s chairman, appears to have been the youngest of those on the original board. Aged 27 in 1884, his land holdings totalled 37,454 acres in 1883 with a gross annual value of £63,778. The 17,000 acres in Glamorganshire provided more than half that gross annual value. But the larger land-area in Shropshire and Worcester was the location of Windsor’s “principal seat”, Howell Grange near Redditch.[43] Windsor was chairman of the Midland Union of Conservative Associations and enjoyed an active career on the Conservative side of British politics. He provided most of the land that the Barry enterprise required for its dock-facilities area, on terms involving low up-front costs balanced by trailing royalties on traffic-activity in the dock when functioning. Beyond that his role in the Barry company does not appear to have been particularly active except as figurehead at public occasions. David Davies was the deputy chairman and de facto CEO of the enterprise. From the records available, it seems unlikely that Lord Windsor ever expected to be called upon to make any significant further injection of share capital into the company after October 1884, except for calls on shares already allotted to him.

Crawshay Bailey II (1821-1887) was a smaller landowner than Lord Windsor, 13,649 acres with gross annual value of £12,888. But in Bailey’s case, the lion’s share of this land (representing over 85 per cent of its gross annual value) was in Glamorgan and Monmouthshire.[44] As a mineral royalty owner Bailey had financial interests in a number of collieries operating on his land, with part of the David Davies and Co. collieries falling into this category. But his evidence in the Committee stage of the 1883 Barry Bill suggests that he was fairly “detached” from the coal industry per se. Williams described this evidence as “bizarre” and Bailey as “the kind of ally who gives aid and comfort to the enemy.”[45] During 1885 and 1886, Bailey’s attendance and participation in Barry board meetings diminished. Neither before his death in April 1887 nor after does there seem to have been any move for his board seat to be taken over by a representative of his heirs (two daughters).

Setting aside the position of the two landowners for the moment, it is clear that the remainder of the Barry company’s core shareholders were men whose capacity to make further significant injections of capital into the Barry enterprise was dependent on two things: firstly, the prosperity of the business concerns operating in the South Wales coal industry which were their own principal economic interests; and secondly whether those same business concerns were themselves proving “hungry” for capital, leaving little of their operating surpluses available for “outside deployment”. The best type of supporting shareholder for a capital-hungry enterprise such as the Barry during its construction phase is someone with a healthy positive cash flow that is generated from a source which is not itself demanding a re-investment of that cash flow.

Changes in the South Wales economic situation

It was the misfortune of the Barry board to find that no sooner had construction on the company’s capital-works commenced than the fortunes of the South Wales coal industry as a whole went into a downturn. The average pithead price for Glamorgan coal, which had been 6.25 shillings per ton for 1884, fell to 5.84 in 1885 and then further to 5.12 in 1886.[46] The slump in demand and prices saw a decline in the total output of coal in Glamorganshire, by about 6.5 per cent between 1884 and 1886.[47] The implied total revenue reduction for Glamorgan coal producers in aggregate from 1884 to 1886 is 23.4 per cent. For David Davies and Co., gross profits for 1884 were £53,761. They fell to £28,339 in 1885 and £12,511 in 1886. During 1884 dividends distributed to the firm’s owners amounted to £61,805. The figure for 1885 was £47,484 and for 1886 zero.[48] It is hard to believe that any of the colliery proprietors on the Barry board would not have experienced significantly reduced profits in their own colliery enterprises under the adverse coal market conditions of 1885 and 1886.

But for the partners in “Ocean Collieries”, the South Wales coal mining business that David Davies controlled, the collapse in dividend distributions from the firm David Davies and Co to zero does not represent a complete picture of the economic squeeze they experienced during 1885 and 1886. While the coal price was high, and demand buoyant, during 1883 and 1884, Davies had committed himself and his partners to substantially increasing their coal production capacity, by establishing two major new collieries. One of these ventures, Garw, was commenced in 1883 and was carried out by the firm David Davies and Co., while for the second a separate partnership was established in 1884 (Davies, Scott and Co), comprising seven of the eleven partners from David Davies and Co., plus four new partners.[49] Garw cost £46,674 to sink, with coal first produced in July 1885. This cost to sink should not be regard as the full cost, since [it] “did not include even the full fitting out costs let alone housing and other services.”[50] The second venture, named the Lady Windsor colliery in honour of the wife of the Barry chairman, was a much deeper colliery (620 yards), and cost £95,875 to sink. Its construction took more than two years with the first working of coal occurring in December 1886.[51]

The funding of these two major new collieries represented a substantial financial commitment for Davies and the other “Ocean Collieries” partners. In rough terms, Garw can be regarding as consuming a sum equivalent to the whole of the dividend distributions of 1885 (and 1886) from the Davies collieries, leaving the partners with around £100,000 of investment funding costs to find during 1885 and 1886 for “Lady Windsor”, and no internally generated cash to go towards that. Davies and his son would need to find about half of that £100,000, and the other thirteen partners (including Riches and Scott ─ both members of the Barry board) the remainder.

Thus by the time the Barry company itself was starting to need serious injections of investment funding, Davies, Riches and Scott had committed themselves in advance, for the 1885 and 1886 period, to major investment spending projects on the development of new collieries as part of their own business enterprises. Among those other of the core-shareholders and directors of the Barry company who were also colliery proprietors, none appear to have been in the same position as Davies, Riches and Scott in this regard.[52] The actions of Davies, assuming his business decision making was not dominated by confidence in his own gut-feelings and intuitions, suggest he expected that either the buoyant demand for coal and high coal prices of 1881 to 1884 would be maintained or that any downturn would be mild so that he would be able to “ride out the storm” while delivering on his personal financial commitments both to his Ocean Collieries and to the Barry enterprise. The actions of the colliery proprietors on the Barry board other than the Ocean Collieries trio suggest that either their expectations regarding the South Wales coal market were substantially more pessimistic than those of Davies, or that they were more concerned than Davies about the downside consequences should that market go into a more severe-than-expected “temporary” downturn. Clearly, for any person without some fundamental optimism regarding the future of the South Wales coal market as at late 1884, it would have made little sense to be a core supporting shareholder in the Barry project. So when looking at Davies compared with the other colliery owners on the Barry board, we are left with questions of appreciation of business risk and of appetite for taking on and bearing such risk.

Looking at Davies’ business career over the years preceding the commencement of the Barry project there is evidence of Davies being inclined on occasions to be something of a “plunger” in his attitude towards business risk. It would also appear that Davies expected those joined with him in the business endeavours he controlled would accept all major decisions made by him “no questions asked.” In a public speech made in June 1873, Davies said:

When you see me … you see the Ocean company. And that is a great advantage. I do not tell you that I am, properly speaking, the whole of the Ocean Company, but … I am the largest single shareholder in the Ocean Company and the remainder have so much confidence in me that they entirely acquiesce in what I do; they never say a word about what I do.[53]

As was noted earlier, the Ocean company was not during this period a limited liability company. Davies held strongly negative views about limited liability companies established under the British Companies Acts, as distinct from Statutory companies such as railways,[54] and resisted the restructuring of Ocean Collieries into a limited liability company until April 1887.[55] On Davies’ appetite for business risk, both of his biographers provide fairly detailed (and highly sympathetic) accounts of the events of early 1866 when Davies over-extended himself financially, had exhausted his capacity to meet his obligations as they fell due, and was rescued by a key group of his workmen volunteering to continue to work, without further pay for a period, and by further cash advances from a supportive Liverpool banker.[56] Davies had clearly been happy for the story of these 1866 events to be told during his own lifetime. The lesson hearers are invited to draw from the story is that if employees, creditors and business partners simply display sufficient confidence in Davies’ business judgement, there will be a “happy ending” for all concerned.[57]

To recapitulate: During September/October 1884 the board of the Barry company had embarked on an investment spending programme expected to consume about £1.4 million over a period of from 3½ to 4 years. To fund that programme the board had “locked-in” about £600,000 of the company’s ordinary share capital ─ which would allow half of the company’s borrowing powers to be exercised, once those ordinary shares which had been allotted became fifty per cent paid-up. (This latter was done in May/June 1886 and £175,000 raised in 4½ per cent debentures.[58]) The remaining £450,000 of the company’s authorised share capital had not been effectively “locked-in”, and therefore nor had the remainder of the company’s authorised borrowings ─ which could only be raised once this tranche of share capital became fifty per cent paid-up. As 1885 passed and the months of 1886 began to tick down, the time available for deferring making arrangements to lock-in the raising of the “second tranche” of share capital began to slip away. But for the directors there were two problems in bringing up such a discussion: (a) the board now knew that the company was going to need more than £1.4 million to complete its dock and railway infrastructure, and that completion of that work was going to take more time; and (b) for the Ocean Collieries people in particular, coming up with the share of that £450,000 “second tranche” that they had “put their hands up for” on 15 October 1884 may now have been looking much more difficult. In addition, there may have been sensitivities about raising any questions that Davies might perceive as indicating any lack of confidence in his having everything appropriately on track.

The Barry board minutes do not record any discussions regarding the “second tranche” of the company’s share capital during 1885 or 1886. But the price at which the first tranche shares were trading suggest that as 1886 progressed there was a lack of confidence on at least someone’s part that the company’s affairs were appropriately on track. From trading at a discount of £1.375 against their paid-up value in April, prices deteriorated to a discount of £2.25 in August.[59] Under such circumstances, any attempt at getting new outside investors to pay full face-value for the un-allotted “second tranche” of ordinary shares would clearly be doomed to failure. And allotting them at a hefty discount from face value would both widen the disparity between the Barry’s total capital funding needs and its authorised capital raising powers, and jeopardise the terms on which the company could borrow funds.

By November 1886, the Barry board must have accepted these unpalatable facts, for a new approach was taken: namely to seek parliamentary authorisation to cancel the “second tranche” £450,000 Barry ordinary shares and create in their place the same number of preference shares in the company. Persons taking up these shares would receive 4 per cent interest on the capital they provided until the Barry’s dock and railway feeders became operational ─ with those payments coming out of the company’s capital funds. From the time the dock and railways commenced revenue-earning, the preference shares (or “prefs”) would have first call on the company’s profits for a dividend of 5 per cent per year, but nothing higher than that.[60] Both the early commencement of a return and the “preference” over the ordinary shares re on-going dividends (and in the event of a liquidation) would make these new Barry prefs less difficult to place than the ordinaries they were to be created in place of. The downsides were the need to budget for the additional outgoings during the construction phase, and the “hiatus” of six months or so while the company’s Bill proceeded through the parliamentary process and the requisite shareholder approvals for the creation and issue of the new prefs were then obtained.

The “hiatus” factor was the greater worry for the Barry board. It would be a tight-run thing whether the new money raised from issuing the prefs, once this could be done, would become available to the company for meeting construction costs etc., before all preceding available sources of funds had been exhausted. This created pressure on the Barry board to resolve the arrangements for issuing the prefs (in particular, securing firm buyers for the whole issue) in advance of parliamentary approval having been obtained. And ideally the process for issuing the prefs should be harmonised with plans for raising such further tranches of investment funding that the company would need to complete its construction programme. But to be seen to be in a hurry, especially in the wake of public comments by Davies that the company was not in need of any share capital from outsiders,[61] would be likely to raise doubts in the minds of would-be buyers of the prefs. Some on the board may have felt that avoiding any signs of undue haste might represent the lesser of two evils ─ even if this put in jeopardy the ability of the Barry company to continue paying its contractors’ bills on time as they fell due.

Under these circumstances, it is easy to see why T.A. Walker should have been interested in how the Barry board was progressing in resolving its capital-funding problems during the late 1886 and early 1887. Contract two had been awarded to Walker for the round-number figure of £200,000 during June 1885 without a competitive tender process. Although contracts 4 and 3 were awarded to contractors other than Walker (in August 1885 and June 1886 respectively), it was Walker’s two contracts that were absorbing over four-fifths of the company’s construction costs during late 1886/beginning of 1887.

This is how R.W. Perks came to be involved in the Barry company’s affairs. In Perks’ own words:

The contributions of the ordinary shareholders became exhausted and large sums were due to the company’s bankers. The Directors decided to raise further capital. Their own resources available for outside investment were exhausted and the Bankers refused to lend more. Mr Walker advised the Directors to see me.[62]

Notes and references

[1] The principal accounts of the history of the Barry Railway are: D.S. Barrie, The Barry Railway, The Oakwood Press, 1962; R.J. Rimell, History of the Barry Railway Company, 1884-1921, Western Mail Ltd, Cardiff, 1923; and Ivor Thomas, Top Sawyer: A Biography of David Davies of Llandinam, Longmans, Green and Co., 1938.

[2] Figures taken from The Investors Monthly Manual, published as a supplement (with separate pagination) to The Economist. For September 1890 the highest and lowest prices were 200 and 190 per centum of par value, (p. 488); October 205 and 199 (p. 539); November 215 and 205 (p. 591); December 220 and 210 (pp. 672-3).

[3] W.J. Stevens, Investment and Speculation in British Railways, Effingham Wilson, London, 1902, p. 202. Stevens reports the dividends paid by the company from its first eight full calendar years of business as 10 per cent p.a. for 1890 and 1891; 9½ per cent p.a. for 1892 and 1893; 10 per cent p.a. for 1894 to 1897. Note that the dividend for each calendar year’s business was declared for the two half-years separately and in arrears (one in August/September of the year itself, one in February/March of the following calendar year).

[4] C. Hamilton Ellis, British Railway History 1877-1947, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1958.

[5] A formal stock exchange in Cardiff was not opened until 1892. But by 1885 there were seven stockbroking firms active in the city, and with Thackeray and Sayce, and E.T. Lyddon & Co at the forefront these brokers cooperated in matching up buyers and sellers of local shares (as well as trading as principals) and publishing trading prices. See R.H. Walters, The Economic and Business History of the South Wales Steam Coal Industry 1840-1914, Arno Press, New York, 1977, pp. 118-9; and R.O. Roberts, “Banking and Financial Organisation, 1770-1914”, Chapter 8 in Volume 5 of Glamorgan County History, University of Wales Press, 1980 (edited by Arthur H John and Glanmor Williams).

[6] R.J. Rimell, op. cit., p. 68.

[7] Financial Times, Tuesday 27 August 1889, p. 1 (“City Topics” column).

[8] On Perks and the Metropolitan Railway, see: A.A. Jackson, London’s Metropolitan Railway, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1986; and David Hodgkins, The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901, Merton Priory Press, 2002. On Perks and the MDR and UERL, see: T.C. Barker and Michael Robbins, A History of London Transport, Volume 2, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1974; A.A. Jackson and D.F. Croome, Rails Through The Clay, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1962; and John Franch, Robber Baron: The Life of Charles Tyson Yerkes, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 2006.

[9] See John Davies, Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1981; M.J. Daunton, Coal Metropolis: Cardiff 1870-1914, Leicester University Press, 1979; and Robin Craig, “The Ports and Shipping c1750-1914”, Chapter 10 in Volume 5 of Glamorgan County History. The third Marquis (1847-1900) succeeded to the title at the age of six months, so that from 1848 the estate was managed by trustees. The trust situation continued after the third Marquis came of age as “he took little interest in estate management” (Daunton, p. 31). The running of the estate was largely in the hands of W.T. Lewis (1837-1914). Although himself a major coal owner, Lewis took a pessimistic view of the expansion of the Welsh coal trade (Craig, pp. 476-7). During 1881 there were discussions between the Bute trustees and the Cardiff corporation about setting up a harbour trust for the Cardiff docks, but in October Bute broke these off and announced he would retain control.

[10] M.J. Daunton, op. cit., pp. 33-34.

[11] The TVR’s charges declined in two main stages from 0.8d per ton-mile at the beginning of the 1880s to 0.575d at the end of the decade. There were cuts in 1883 coinciding with the first attempt by the Barry Promoters to get parliamentary authorisation for their scheme. The 1889 reduction came just as the Barry system was preparing to open for full operation. (See p. 459 of Harold Pollins, “The Development of Transport, 1750-1914”, Chapter 9 in Volume 5 of Glamorgan County History.)

[12] For more detail see D.S. Barrie, op .cit., pp. 159-161.

[13] Trevor Boyns, “Growth in the Coal Industry: the Cases of Powell Duffryn and the Ocean Coal Company 1864-1913”, in Colin Baker and L.J. Williams (eds.), Modern South Wales: Essays in Economic History, p. 164. David Davies and Co was not a limited liability company. Formed as a partnership of 6 members in 1864, it operated from 1867 until the end of March 1887 as a joint stock company of 11 members with unlimited liability. See R.H. Walters op. cit., pp. 97-101.

[14] Times, Wednesday 6 August 1884, p. 11.

[15] On the parliamentary struggle, see Ivor Thomas op. cit., chapter 25; and Herbert Williams, Davies the Ocean: Railway King and Coal Tycoon, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1991, Chapter 20. The source for the Glamorgan coal prices is R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 359.

[16] For more detail see D.S. Barrie, op. cit., pp. 163-165.

[17] The National Archives (TNA), RAIL 23/2, “Barry Dock and Railways Co., Directors Minute Book 4 September 1884 to 12 March 1890”.

[18] Robin Craig, op. cit., p. 480.

[19] Times, Friday 26 September 1884, p. 11.

[20] Times, Wednesday 1 October 1884, p. 2 (repeated 2 October 1884, p. 14, and 4 October 1884, p. 13).

[21] TNA, RAIL 23/2.

[22] loc. cit.

[23] Thomas Skinner, Stock Exchange Year Book for 1887, Cassell and Co., London, 1886, p. 71.

[24] D.S. Barrie, op. cit., p. 159.

[25] See Herbert Williams, op. cit., pp. 114-5; and D.S.M. Barrie, “David Davies (1818-1890)” in David J. Jeremy (ed.), Dictionary of Business Biography, Butterworths, London, 1984, Volume 2, pp. 21-23.

[26] D.S. Barrie, The Barry Railway, p. 161.

[27] TNA, RAIL 23/2.

[28] loc. cit.

[29] See Patricia Spencer-Silver, Tower Bridge to Babylon: The Life and Work of Sir John Jackson, Civil Engineer, Six Martlets Publishing for The Newcomen Society, Sudbury, 2005.

[30] Hamilton Ellis, op. cit., p. 35.

[31] See R.P.T Davenport-Hines, “Sir John Wolfe Barry (1836-1918)” in David J. Jeremy op. cit., volume 1, pp. 195-8.

[32] The official opening ceremony was held 17 September 1884. Public services round the full circle commenced Monday 6 October 1884. (A.A. Jackson, op. cit., p. 110.)

[33] The headings were joined on 17 October 1884. John Daniel, “The Severn Railway Tunnel”, chapter 8, p. 2 on The Great Western Archive website (www.greatwestern.org.uk/severn8) viewed 27 September 2002. There is other evidence of Walker’s good repute in South Wales at this time. In April 1884, Walker had completed enlargements to Penarth Dock for the TVR (with Sir John Hawkshaw as engineer). In June 1884 he took over work on the Llanisham Reservoir for the Cardiff Corporation after the corporation had encountered problems with the contractors previously engaged to do the work. At the beginning of the decade he had constructed the Prince of Wales dock in Swansea.

[34] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[35] The dam towards the eastern end of Barry island was closed in March 1886. The dam at the western and proved much more difficult and was not closed until July 1886. See pp. 135-6 of John Robinson, “The Barry Dock, including the Hydraulic Machinery and the Mode of Tipping Coal”, Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, volume 101, 1890, pp. 129-185.

[36] Times, 1 October 1884, p. 2.

[37] J. Robinson, op. cit., p. 137.

[38] ibid, p. 152.

[39] TNA, RAIL 23/2.

[40] For a summary of the Buenos Aires dock project see R.W. Perks, “The New Docks at Buenos Ayres” (sic), letter to the editor, Times, 17 July 1897, p. 18.

[41] TNA, RAIL 23/2. The figure of £712,300 was in material presented to the Barry board meeting of 16 December 1887. The full extent of this cost increase may not have been evident to the Barry board during 1886.

[42] (David Young, A Noble Life: Incidents in the Career of Lewis Davis of Ferndale, C .H. Kelly, London, 1899, p. 88). In October 1887, Lewis Davis retired from the Barry board (due to ill health) and was replaced by his son Frederick Lewis Davis. Somewhat confusingly, the Lewis Davis enterprise was titled “David Davis and Sons”. The enterprise was established by Lewis’s father David Davis senior (1797-1866). Lewis shared management responsibilities with his brother David Davis junior (1821-1884) from 1867 until the latter’s death. This “David Davis junior” was prominent in the early stages of the promotion of the Barry enterprise.

[43] J. Bateman, The Great Landowners of Great Britain and Ireland, London, 1883 (reprinted Leicester, 1971).

[44] ibid. Bailey was the only son of the more famous Crawshay Bailey I (1789-1872), iron-master and MP.

[45] Herbert Williams, op. cit., p. 199.

[46] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 359.

[47] ibid., pp. 346-347.

[48] Trevor Boyns, op. cit., p. 166.

[49] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 101.

[50] ibid, p. 89.

[51] ibid, p. 90. The nomenclature should not be taken as a sign that Windsor was involved as a partner in Davies, Scott and Co (or David Davies and Co).

[52] R.H. Walters op. cit., provides a full listing of major new colliery sinkings in South Wales during the 1880s, and also of changes in ownership of already existing collieries. There were enterprises other than Davies investing in developing significant additional capacity during the 1884 to 1887 period (notably Powell Duffryn, and the Lewis and Cope enterprise), but these were not firms whose principals were core shareholders in the Barry. Cory Brothers expanded by buying two already existing collieries in the Rhondda during 1884 (Gelli and Tynybedw) but there is no evidence of the Cory enterprise needing major injections of “new capital” from its proprietors in consequence of this.

[53] Quoted in Ivor Thomas, op. cit., p. 198.

[54] Herbert Williams, op. cit., p. 174.

[55] At that point the partners’ capital in the two predecessor firms totalled £553,140. This was converted into shares in the new entity, Ocean Coal Company Ltd. There was no attempt to offer shares to the general public, or to establish any market trading in the shares. This, together with the timing, may suggest that Davies’ partners became more sensitised to their “unlimited liabilities” during the build-up of financial stresses on Davies pending a resolution to the Barry funding situation.

[56] See Ivor Thomas, op. cit., Chapter 12 and Herbert Williams, op. cit., pp. 93-95.

[57] Not every story of a “confident” bank manager concludes with a “happy ending”. One of Davies’ original partners in Ocean Collieries was Morgan Joseph, whose brother Thomas Joseph had married Louisa, a sister of Lewis Davis. Thomas Joseph was proprietor of several collieries including Dunraven in the Rhondda. In November 1881, the Sheffield and South Yorkshire Permanent Benefit Building Society, to which Joseph already owed over £25,000, advanced him a further £41,000. In July 1882 Joseph filed a petition in bankruptcy. Its loans to Joseph caused the Sheffield and S. Yorks building society to go into liquidation, and the liquidators successfully took legal action against the society’s managing director (and some of his colleagues) over the £41,000 loan having been made without proper diligence or on proper security. See Times 19 October 1882, p. 12; 7 October 1886, p. 4; and 7 November 1889, p. 3.

[58] TNA RAIL 23/2. The board decision was made on 21 May 1886, a prospectus issued in June, and allotments approved on 16 July 1886. Only £25,000 appears to have come from directors and their associates, with £150,000 raised through brokers who underwrote that segment of the raising.

[59] See Rimell, loc. cit.

[60] The notice that the Barry company intended to apply to Parliament “in the ensuing session”, to introduce a Bill to give these powers appeared in the London Gazette of 26 November 1886 (pp. 5920-21), and was itself dated 19 November 1886.

[61] In his testimony before the House of Commons committee on the 1883 Barry Bill, Davies had said that the core group of original investors in the company were happy to find all the share-capital the company needed: “We could get the money all in one day; there is no difficulty about the money.” (quoted in Herbert Williams, op. cit., p. 198).

[62] p. 100 of R.W. Perks, Sir Robert William Perks, Baronet, Epworth Press, London, 1936 (henceforth cited by its subtitle: Notes for an Autobiography).