Chapter 5: Methodist Layman

A scan of the original unannotated document can be accessed from the HathiTrust Digital Library collection at

The Life-Story of Sir Robert W. Perks, Baronet, by Denis Crane.

[start of page 96 in original pagination]

Chapter V: Methodist Layman

Having followed briefly the course of Sir Robert Perks’s professional and commercial interests, from their modest beginnings in De Jersey & Micklem’s office to their almost world-wide developments, we must now retrace our steps to indicate another line of activity simultaneously pursued by him with equal ardour and, throughout one notable period at least, with an extraordinary expenditure of time and energy. I refer to his services to Methodism.

One of the early fruits of his discreet up-bringing, in which, as we have seen, the emphasis was laid upon high example rather than upon moral cramming to achieve its ends, was that at quite a youthful age he took an active part in the life of the Church. Little

[start of page 97 in original pagination]

imagination is needed to see what would have been the result upon a nature such as his of a catechetical and introspective training. Like thousands of other self-reliant lads he would have revolted, or at any rate have nursed his resentment until parental restraints were removed, and then turned in repugnance to secular concerns. His father’s way was better. By discussing with him almost on terms of equality the affairs of the Church, interest was developed from within, rather than enforced from without.

At sixteen, therefore, we find him employing his gifts, with a devotion rare in one so young, in Sunday-school work at Highbury. He acted as secretary and librarian; and subsequently as the teacher of a large class of youths. He was also instrumental in starting a school at Green Lanes, of which he became superintendent. To such work among the young he devoted the greater part of the scanty leisure of six-and-twenty years.[1],[2]

At Highbury, too, an idea occurred to him which has since borne good fruit. He noticed that the annual meeting of Methodist preachers’ children was not turned to practical account; so in concert with the late Dr. Robert

[start of page 98 in original pagination]

Newton Young, he started the Preachers’ Children’s Association, based on the principle of a five-shilling donation from every Methodist preacher or preacher’s child. It was a family affair, and subscriptions outside the magic circle were neither asked nor taken. This useful fund has been the means of bringing help for close upon thirty-five years to numberless Methodist ministers’ children.[3] The democratic principle upon which it was founded, namely, ‘each person five shillings,’ was adopted later, in 1898, when the Twentieth Century Fund was started on the basis of ‘one person one guinea.’

On his removal after his marriage to Chislehurst, where he had built himself a residence, Sir Robert led for fifteen years, to use his own words, ‘the regular, quiet, unostentatious life which a hard-working professional man crowded up with business must lead.’ ‘Methodism, my business, and my home,’ he adds, ‘absorbed all my attention.’ The share claimed by Methodism was by no means inconsiderable, compared with what most men similarly placed find themselves able to give. A handsome Gothic church had been built at Chislehurst some ten years previously,

[start of page 99 in original pagination]

and here gathered a little group of Methodist laymen whose names have since become house-hold words in the denomination. Sir Clarence Smith[4], the late Mr. James Vanner, his brother, Mr. William Vanner[5], and Sir George Hayter Chubb[6], were all of the number. In 1881 Sir Robert and Sir George were joint society stewards of the church, and in many other relations they and their colleagues worked earnestly for the good of the community.

These, it must be remembered, were among Sir Robert’s most militant days, and his pronounced views and unequivocal speech made him at once a terror to evildoers and a spur to them that did well. There is indeed a tradition that his zeal led to his being made an ‘exhorter.’ The tradition also adds that for some reason or other he was eventually ‘struck off the plan.’ As Sir Robert at one time and another has had a good deal to say about preachers and preaching, this bit of gossip seemed to promise some biographical data of uncommon interest; but diligent inquiries have elicited nothing, save that in 1884 he was temporarily appointed to conduct services in certain outlying villages then being evangelized, there being a shortage of local preachers quali-

[start of page 100 in original pagination]

fied for such pioneer work; that his superintendent minister, the Rev. Wesley Butters, promised not to worry him about coming on ‘full plan’; and that in 1892, when the necessity for these special labours ceased, his ‘note’ was voluntarily resigned. It is worth mentioning, however, that during this period he interested himself particularly in a Sunday school at the little village of Widmore, and that as the result of his labours its roll was increased from forty to more than three hundred[7]. Sir Robert at this time was of real assistance in the Sunday night prayer-meeting; and in all good work throughout the circuit he and his devoted wife were ever ready with sympathy and service. By the older Chislehurst residents he is still spoken of with respect and esteem.

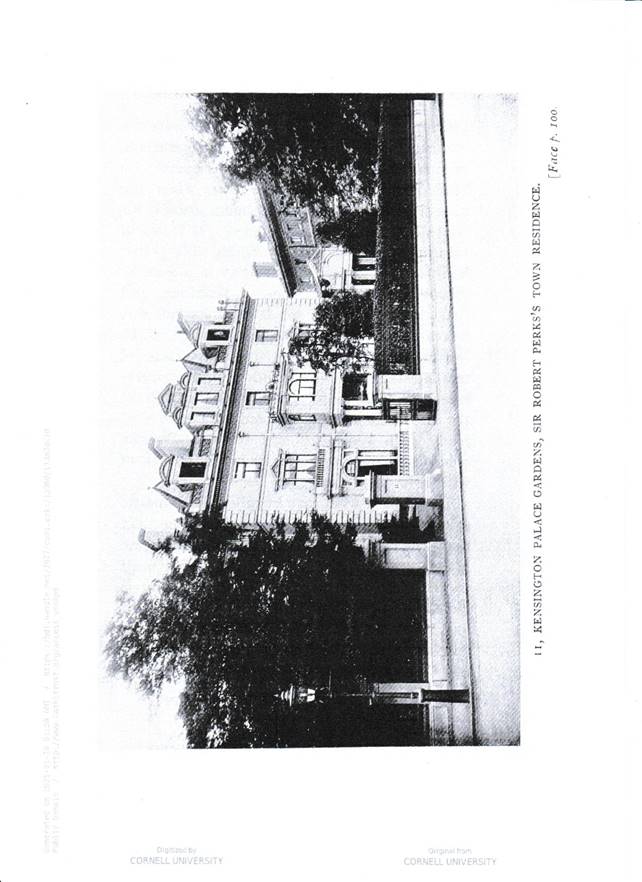

To complete what may be called the domestic side of his Methodist life, it should be said that when he removed to Kensington, some fifteen years ago[8], he at once attached himself to the church at Denbigh Road, Bayswater. Here he has held numerous offices and has taken an influential part in the circuit administration. Inevitably his social eminence and Connexional reputation have given him

[start of page 101 in original pagination]

a leading position among his fellow members; but it is admitted on all hands that his sway is wholly genial, and his long tenure of office has been entirely at the wish of his brethren. Ministers who have travelled in the circuit declare that nowhere is Sir Robert more popular or more beloved than at Bayswater.

Friends have also furnished me with many instances of his kindly interest in all who are in any way connected with the circuit, and of his practical concern for the well-being of the ministers. Once, during a time of special prosperity, when unusually large congregations were gathering, he moved for the increase of the preachers’ stipends, on the ground that it was not fair for the church to appropriate all the proceeds of its ministers’ popularity. The salaries were accordingly raised. Some one objected, however, that it might be hard, when less popular preachers came into the circuit, to maintain so high a standard. But the objection was overruled. Sir Robert pledging himself personally to ‘look after the ministers’; a pledge which, I am informed, he generously fulfils.

Personal kindnesses of a private character

[start of page 102 in original pagination]

are still more numerous, but for obvious reasons cannot be divulged. The following incident, however, is typical. Some years ago, a man holding a responsible position in the City, whose wife was a member in the circuit, was foolish enough to attempt a petty fraud on the Metropolitan Railway, but was detected, and in due course was summoned to appear before the magistrate. The minister, in the course of a casual visit, discovered the trouble into which the family had been plunged. The wife was in deep distress; her husband’s position and her own good name were alike imperilled.

Aware of Sir Robert’s connexion with the railway, the minister promised to see what could be done, and hurried away to Kensington. Unfortunately, his friend was out of town, and had left strict instructions that his address was not to be made known. The urgency of the case, however, prevailed, and a letter was at once dispatched to Sir Robert asking him, for the sake of the man’s wife, to use his influence to stop the proceedings. This was on the Saturday; on the following Tuesday the case was to come into court. On the Monday word was received from Sir Robert

[start of page 103 in original pagination]

that he had done as requested, and that instead of the man being prosecuted he himself would admonish him in person. While picturing the culprit’s relief at his lucky escape, one can imagine his feelings under the alternative ordeal.

Acts of this kind are, of course, simply what one would expect from a Christian gentleman of position and influence; the only distinction is that in Sir Robert’s case, according to his friends, they have been more than usually numerous, and display on his part a delicacy of feeling of which those who know him only in business or in debate might not think him capable. For the rest, he is, when at home, a diligent attendant at public worship; he prefers sermons neither too theological nor too consciously ‘up-to-date’; while in regard to the form of service, his tastes lie in the direction of simplicity and informality rather than ornateness and ceremony.

Turning now to the wider aspect of his relation to his Church, we find him occupying a position at once unique and influential. For many years he has been regarded as the outstanding representative of the laity of Methodism. It is only fair to say, however.

[start of page 104 in original pagination]

that, much as his own energy, wealth, and love of liberty may have served to win him this position, they have not wrought alone. At an early age the honours of leadership were voluntarily bestowed upon him, and on a hundred important and historic occasions he has been singled out to fill the position of chairman or principal lay speaker. His first Methodist public speech, for example, was delivered from a platform which included men so distinguished in their time as Dr. Morley Punshon, the Rev. Thomas Champness, and Mr. S. D. Waddy, Q.C., M.P. This was in 1877, at the centenary of the stone-laying of that Methodist Mecca, City Road Chapel, when he was only eight-and-twenty[9]. His speech on that occasion showed few signs of immaturity, and adumbrated in a remarkable manner some of the principles for which he has since steadfastly contended.

‘In some sense I seem to represent,’ he said, ‘a generation of Methodists who have not yet been called to discharge the duties and obligations of the Church — that next generation, to whose keeping will in due time, I presume, be entrusted the sacred ark of our Church’s constitution. ‘Having spoken of the principles

[start of page 105 in original pagination]

for which, in his opinion, Wesley’s Chapel stood, he proceeded : ‘Let us rejoice in that peculiarity of our Church, that, while its principles are fixed and unalterable, its plans of administration are flexible and progressive. What the next great popular movement of Methodism may be I cannot tell, but I think the day is not far distant when there will come forth an earnest and invincible desire to reunite all those sections of the Methodist family which have become separated and dispersed.’ He concluded with a characteristic warning against the ‘sensuous displays’ which he perceived to be growing up in the worship of other Churches. Methodists must not loiter on the King’s highway to watch the ‘marionettes of religious society,’ but must cling to the simple and sublime services handed down to them by their fathers.

From that day forward his position as a leading layman was assured. It fell to his lot to take part, together with such eminent leaders as Dean Farrar, Dr. Clifford, Dr. Monro Gibson, the President of the Wesleyan Conference, and other distinguished ministers, in the public dedication of Wesley’s House, in 1898[10]; and to propose the toast of ‘The Closing Century,’

[start of page 106 in original pagination]

to which Sir John Lubbock and Dr. Joseph Parker, representing respectively Science and Religion, responded, at the reopening of Wesley’s Chapel, after the renovations, in the following year[11]. He has also twice served — in 1881 and 1901 — as lay delegate to the Oecumenical Methodist Conference, on the first occasion acting as Secretary of the Publication Committee,[12] and on the second as one of the Treasurers. Relating his experience in the former capacity he said: ‘I remember that the Rev. W. Arthur drafted the “Note by the Editors” which appears on the first page of the report of the proceedings of the Conference. Mr. Arthur concluded his note with a hope that the perusal of the report would advance “the cause of the Redeemer by inspiring the followers of Christ and John Wesley with greater zeal in working for the conversion of the world.” “Don’t you think, Mr. Arthur,” I said, “that it would be better to leave out John Wesley and let Jesus Christ stand alone?” “Yes,” replied the veteran missionary, striking his pen through the name of Methodism’s human founder.’[13]

Sir Robert has consistently advocated the claims, and championed the cause, of those

[start of page 107 in original pagination]

devoted men who, without fee or earthly reward, consecrate their time and talents to the office of local preacher. He has paid many glowing tributes to the value of their services, and has more than once asked that they, with other unpaid workers, should receive greater recognition upon occasions of public importance. Thus in 1901, when the Conference was about to offer a loyal and dutiful address to King Edward on his accession. Sir Robert urged that the deputation charged with the duty of presenting the address should not be drawn exclusively from the official and titled elements of Methodism, but should consist, conjointly with the President and Secretary of the Conference, of some of the men who had borne the burden and heat of the day. He suggested that the oldest local preacher, the oldest class-leader, and the oldest superintendent of a Sunday school, should be included, rather than that an attempt should be made to impress the Throne by sending only doctors of divinity and representatives of the titled class.

These democratic views, and his passionate dislike of anything resembling a priestly conclave, led him some ten or more years

[start of page 108 in original pagination]

ago to advocate the admission of professional reporters, representative of the general Press, to the Conference sessions. The question had been raised at the instance of the Institute of Journalists, which appealed for the removal of an anomalous embargo. A committee was appointed by the Conference to consider the matter, but its report pronounced against the appeal, on the ground that those already accredited to forward intelligence were better qualified to deal with the topics discussed than professional reporters could possibly be. Sir Robert repudiated the idea, which the exclusion of the general Press tended to promote, that the Wesleyan Conference was a secret assembly in which mysterious things were sometimes done that ought not to get abroad. He pleaded for a wider dissemination of the reports of its proceedings, arguing that members of the Conference would speak under greater responsibility if they felt that what they said would be published on the housetop.[14]

One of Sir Robert’s outstanding characteristics is his faith in his Church. While some men, as they have risen in life, have forsaken Methodism at the dictates of a despicable

[start of page 109 in original pagination]

pride, Sir Robert has cleaved to it with reasoned and growing conviction. The ill-conceived desire to graft upon Methodism the ecclesiastical usages, titles, and ceremonial of the Anglican Church, in the belief that by so doing Methodists would ‘assert their equality,’ he has denounced with withering scorn, and to it he attributes the alienation of thousands of his Church’s educated and thoughtful sons. On account of its elasticity and ready adaptability, Methodism, he believes, is the most popular and effective form of organized Christianity in the United Kingdom. ‘Her pastorates,’ he once said, ‘are not “livings,” and her preachers are not hirelings; they do not mutter ancient shibboleths; they have not to rely, for the effect of the proclamation of the gospel, upon sensuous externals. They have won their way to the hearts, and enjoy to-day the confidence, of the British people, because they live the gospel they teach.’

Years ago, when a reception was given to the Conference at the London Guildhall, he told an interviewer:

‘Personally I do not attach much importance to Methodism’s receiving the patronage either of the State or of the great municipalities,

[start of page 110 in original pagination]

or even of Royal personages. The great charm of the Methodist Church since its foundation by Wesley has been its independence and its reliance on the support of the masses of the people. We have never fawned upon the aristocracy, nor have the aristocracy patronized Methodism. We do not trouble ourselves very much because the President of the Conference is not officially invited, like the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Chief Rabbi, or Cardinal Vaughan, to the Queen’s Garden Parties. Our laymen are there in large numbers, simply as prominent politicians or citizens. But it must not be forgotten that the City of London was in its most progressive and brilliant days the staunchest patron that Nonconformity ever had, and it is most gratifying, therefore, to any Free Church to see its Chief Assembly entertained by the Corporation of the first city of the Empire. The reception, therefore, of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference by the Corporation marks one of those new stages in the recognition of Methodism as one of the most vital moral and social forces of the age.’[15]

Sir Robert once had the pleasure of expounding the origin and economy of his

[start of page 111 in original pagination]

Church to the late Mr. W. E. Gladstone, who proved to be a deeply interested inquirer. As the incident possesses an interest all its own, and has been told by Sir Robert himself at some length, I quote it here in extenso.

‘About ten years ago I happened to be at a dinner-party with Mr. Gladstone. My neighbour, Mr. John Morley, who was sitting between Mr. Gladstone and me, was unexpectedly called away to the House of Commons about ten o’clock, and as he rose to leave he whispered to me: “Slip into my chair and talk to the Old Man.” Mr. Gladstone noticed me doing so, and turning round suddenly and facing me, he said:

‘ “You are a Methodist, Mr. Perks, are you not?”

‘ “Yes, I am, Mr. Gladstone,” I replied.

‘ “Do you belong to the Old Body?”

‘ “Yes, I belong to the original foundation of Mr. Wesley; but, Mr. Gladstone,” said I, smiling, “we call it a Church and not a Body.”

‘ “Ah,” he replied, heaving a deep sigh, “that raises an issue which has perplexed all Christendom. But now,” said the old man, resting his elbow on the table and placing his hand to his ear, “tell me, Mr. Perks, how

[start of page 112 in original pagination]

many sections there are of your Methodist Church (smiling as he used the word, as though he thought he was pleasing me), and then tell me what were the causes of their various secessions; and then tell me what are their doctrinal differences; and then explain to me their various distinctive ecclesiastical usages.”

‘I was alarmed at the long vista which the question opened up, but there was Mr. Gladstone waiting, with his hand to his ear, expecting from a Methodist layman, then less than half his age, an instantaneous and complete answer.

‘So I plunged right into the absorbing subject. I explained the rise of the New Connexion, the birth and growth of Primitive Methodism, the origin of the Bible Christians, the sad conflicts which led to the splitting away of the Free Methodists and the Reformers. Mr. Gladstone listened intently, saying very little. At length he said:

‘ “Now, Mr. Perks, we will leave the past and deal with the present. What are your doctrinal differences?”

‘ “We have none, Mr. Gladstone,” I replied.

‘ “Would to God,” said the aged statesman, “that my beloved Church could say the same.”

[start of page 113 in original pagination]

‘We had got thus far in our talk when a little incident happened, which showed the veteran Liberal leader in an aspect which was at the time a revelation to me, for I had never associated Mr. Gladstone with humour, though in after years I had more than one opportunity of witnessing in the House of Commons his marvellous command of humorous but withering satire.

‘At the dinner-table there was a man sitting exactly opposite, who did not like the conversation. He wanted Mr. Gladstone to talk about something else. So, interposing, he asked what seemed to me a very silly question.

‘ “Do you know Chester, Mr. Gladstone?”

‘ “Yes, a little,” was the reply, an ominous smile playing about the mouth. “Do you know Chester, Mr. ——?”

‘ “Not very well,” said the unwary questioner.

‘ “Well, if you go to the city of Chester you will find a confectioner’s shop in such a street (and Mr. Gladstone gave the number). Go into that shop and you can buy a hot mutton pie, deliciously hot (and here Mr. Gladstone screwed up his eyes, and his face beamed with

[start of page 114 in original pagination]

delight as he recalled the taste and smell of those savoury pies), and all for threepence.

‘ “Now, Mr. Perks,” said he, turning again to me and speaking in a deep, sepulchral voice, “let us resume where we left off.”

‘We talked an hour that night. We discussed the effect of the itinerancy upon the Church, the relative powers of the clergy and the laity, the tests of membership, and the doctrinal standards of Methodism.

‘Mr. Gladstone did not forget our talk. Some years after, alluding to a subject we were talking about, he said:

‘ “This is not so interesting, Mr. Perks, as the penny a week and the shilling a quarter!” ’[16]

End Notes to Chapter Five

[1] Crane’s source for this paragraph appears to have been a passage in Perks’s article “My Methodist Life” published in the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine of 1906, which read: “In 1865 we left City Road … for the rural delights of Highbury. Here I began Sunday-school work, acting as school secretary, librarian and subsequently the teacher of a large class of men. For twenty-six years I was busily engaged as a Sunday-school officer or teacher, starting two schools — one at Green Lanes and another at Widmore — of both of which I was superintendent” (op. cit., p. 96). It might be worth noting that this passage does not state that Perks began his Sunday-school work when aged sixteen. Although the Perks family relocated to Highbury in August 1865 (or thereabouts), R.W. Perks spent the 1865-66 academic year as a boarder at Henry Jefferson’s school in Wandsworth (see note 12 to Chapter Two). It would seem more likely that Perks commenced regular Sunday-school work after he left the Jefferson school and was living in the parental home in Highbury on a more continuous basis.

[2] The Wesleyan Methodist Chapel at Green Lanes was opened “for divine service” on 15 May 1874 (Islington Gazette, 26 May 1874, p.2). It seems likely that the Green Lanes Sunday school commenced soon after that date, or possibly somewhat earlier. The fifth anniversary of the school was celebrated in April 1879, with Perks presiding at a public meeting held on the evening of Monday 7 April. He was introduced by the Rev. J. Hutcheon, who referred to him as “the father of that Sunday School.” And it was reported that Perks had been the originator of the school’s series of annual prizes for “Stories without names” (Islington Gazette, 11 April 1879, p.3).

[3] This paragraph is closely modelled on a passage in Perks’s 1906 “My Methodist Life” article which appears shortly after the one quoted in note 1: “An idea occurred to me when at Highbury which has borne good fruit. I noticed that the annual meeting of Methodist preachers’ children was not turned to practical account; and I started, in concert with Dr Robert Newton Young, the Preachers’ Children’s Association, based on the principle of a 5s. donation from every Methodist or preacher’s child.” Robert Newton Young (1829-1898) was elected President of the W.M. Conference in 1886. The John Rylands Library at Manchester University holds a letter signed by R.W. Perks, dated 12 May 1874, which invites the Rev. L.H. Tyerman to make a contribution towards the expenses of the annual Preachers’ Children’s Meeting, and to send it to his “co-secretary”, the Rev. R.N. Young. The initiative cited by Crane here probably dates from not long after the time of that letter. At the annual gathering of the Wesleyan Ministers’ Children’s Association held on 4 July 1888, it was stated that “The society has been in existence for something over a dozen years,” and that its income “varied from £300 to £350 a year” (Methodist Times, 12 July 1888, p.473). The concluding sentence of Crane’s paragraph here is also a very close approximation of a sentence from Perks`s 1906 “My Methodist Life”.

[4] Clarence Smith (1849-1941) was the oldest son of Wesleyan minister Gervase Smith (1821-1882) who Crane referred to in Chapter One (p. 18). During the early 1870s Clarence Smith lived with his parents at 13 Leigh Road, Highbury — very close to the Perks family`s home at 9 Leigh Road. Clarence became a member of the London Stock Exchange in 1874, and was married at Highbury Wesleyan Chapel in June 1875. He then established his own home in Chislehurst, where his eldest child was born in July 1876. He was Sheriff of London 1883-84, M.P. for Hull East 1892-95, and was knighted in 1895.

[5] James Engelbert Vanner (1831-1906) and William Vanner (1834-1900) were both among the lay representatives at the 1878 W.M. Conference — the first W.M. Conference to admit lay representation. Also among the lay representatives at that Conference was their elder brother John Vanner (1822-1902). This was a unique case of three brothers being among the representatives. John Vanner lived in Banbury, where he was a neighbour of R.W. Perks’s father-in-law William Mewburn. When John Vanner’s daughter Sarah Elizabeth married at the Marlborough Road Wesleyan Chapel, Banbury, in February 1877, “Miss Edith Mewburn” and R.W. Perks were reported as being in the “bridal party” (Banbury Advertiser, 15 February 1877, p.4). For more on the Vanner Family, see the Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland.

[6] George Hayter Chubb (1848-1946) was the second son of John Chubb (1815-1872) who, with his father, had developed the successful lock and safe business whose name remains well-known today. George Hayter Chubb was also among the lay representatives at the 1878 W.M. Conference, being the third-youngest out of the 240 there. R.W. Perks was the second-youngest. For more on the Chubb family, see the Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland.

[7] Crane’s source here appears to be the unsigned article “Mr R.W. Perks, M.P.” published in The British Monthly, January 1903. This stated (at p.90): “At the little village of Widmore, near to Chislehurst, he turned a school of forty into one of more than three hundred.”

[8] R.W. Perks bought 11 Kensington Palace Gardens in February 1894 (London Metropolitan Archives, MDR 1894/6/384). In 1971, a two-part article on Kensington Palace Gardens by Mark Girouard was published in Country Life: “Town Houses for the Wealthy” (11 November 1971, pp.1269-71) and “Gilded Preserves for the Rich” (18 November 1971, pp. 1360-63). Girouard noted that only one aristocratic household lived in the street: “It was the richer of the new rich, without the desire or social confidence to venture into aristocratic quarters who came to Palace Gardens” (p.1361). The same point was made in volume 37 of the Survey of London: “In general it was an aristocracy of wealth rather than birth that was attracted to the road, its social character being aptly summed up in the nickname ‘Millionaires’ Row`.” (op. cit., p.161). For more on the context of Perks’s move from Chislehurst to Kensington Palace Gardens, see pp.3-4 of Owen E. Covick “Mapping the career of a businessman who was an ‘independent operator’ and who left no substantial papers: the case of Sir R. W. Perks 1849-1934”, Paper presented to the 2005 Conference of the Association of Business Historians, Glasgow, May 2005.

[9] The meeting Crane refers to here was held on Wednesday, 24 October 1877.

[10] The formal dedication service took place on Wednesday 2 March 1898. On the evening of Monday 28 February 1898, Perks had chaired a “great representative meeting”, at which the speakers included: Dr Farrar, Dean of Canterbury, representing the Established Church; Dr Clifford representing the Baptists; and Dr Gibson representing the Presbyterians. See The Methodist Times, 3 March 1898, p. 131.

[11] This ceremony took place on Friday 7 July 1899, and was widely reported in the press.

[12] The 1881 Oecumenical Methodist Conference was the first in the series and was held in England during September 1881. Four hundred Members attended the Conference, two hundred from the Western Section (i.e. North America) and two hundred from the Eastern Section (including Australasia). The Wesleyan Methodist Connexion hosted the proceedings, and was represented at the Conference by 44 ministers and 42 laymen, all elected at the W.M. Conference of August 1881. Perks was the second youngest of the 42 W.M. laymen elected. On the 14 September 1881 he was appointed by the Conference to be one of the five editors of the printed volume of the Proceedings of the Conference. He was the only layman among the five. At the W.M. Conference 1890, Perks was elected to be one of the 41 W.M. lay representatives at the second Oecumenical Methodist Conference to be held in the United States in 1891. He was ranked seventh in the polling list (see The Methodist Times, 14 August 1890, p.831). But at the W.M. Conference in July 1881, Perks “intimated that numerous engagements would prevent” his attending the October Conference in Washington (The Methodist Times, 20 July 1891, p.772).

[13] Crane’s quote here is taken from pp.97-98 of Perks’s article “My Methodist Life”, published in The Wesleyan Methodist Magazine of 1906.

[14] It was at the W.M. Conference of 1889 that Perks had expressed the views Crane recounts here regarding the admission of professional reporters to the Conference. Perks had been the seconder of the successful motion to refer the application of the Associated Institute of Journalists to a committee. In the debate over the committee’s recommendation to maintain the status quo, Perks: “asked what would be the disadvantage of admitting the professional reporters. He thought the brethren would speak with more awe if they knew they would be reported far and wide. Reporters are admitted to the Church Congress, the meetings of the Presbyterians and the Congregational Union, and to the Irish Conference, and he disagreed with the finding of the committee” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 6 August 1889, p.3). Nevertheless, the committee’s recommendation was supported by a majority vote, and professional reporters were not admitted. At the following year’s W.M. Conference, the Institute of Journalists formally submitted their application once more. Once again the subject was referred to a committee, and once again the committee’s recommendation was in favour of the status quo. But this time Perks had the numbers to overturn that recommendation. Presumably for “face-saving” purposes the motion that was passed was to the effect that professional reporters should be admitted to the Representative Session of the 1891 Conference, with a committee appointed to draw up a set of “proper regulations” to apply to the subject. (See The Methodist Times, 7 August 1890, p. 798).

[15] The London Guildhall reception that Crane refers to here was held on Wednesday 27 July 1899. This was the first time that the City Corporation had “entertained” one of the non-conformist bodies. The Corporation voted 600 guineas to cover the costs (The Leeds Times, 5 August 1899, p.3). Crane does not mention that on the immediately following evening, a second reception was held for the Conference delegates. The report on the Conference published in The Leeds Mercury, 29 July 1899, p.5 included: “A reception was given by Mr. R.W. Perks, M.P., on Thursday evening at his palatial residence in Kensington Palace-gardens. There were fully nine hundred invited guests present. In some respects it was a more brilliant gathering than that of the previous evening at the Guildhall.”

[16] The passage which Crane quotes “in extenso” here was originally published in The Methodist Recorder in December 1898 as a signed piece by Perks, under the title “Mr. Gladstone and Methodism”. It was reproduced in full in a number of newspapers, including The Manchester Evening News of 23 December 1898, at p. 3. The opening line suggests that the conversation Perks recounts here took place around late 1888. That was before Perks had become a member of Parliament, but after he had been endorsed by the Liberal party to be its candidate for the seat of Louth (in Lincolnshire) in the next election to be held there. On Wednesday 30 July 1890 Perks hosted a dinner at the National Liberal Club at which about forty leading Wesleyan laymen were invited (as Perks’s guests) to meet Gladstone. See The Times, 31 July 1890, p. 4. But John Morley does not appear to have attended that July 1890 dinner. The occasion of the conversation reported here may therefore have been an earlier and less public function. Gladstone’s diaries may cast some light on this.