This article reproduced with kind permission from The Railway & Canal Historical Society.

Click the blue journal cover image to access the full journal directly from their archive.

It would thus seem clear that by late 1886, T.A. Walker ─ himself a wealthy, respected and successful man of business ─ had developed a high regard for Perks as a source of financial advice as well as legal advice. It is not clear when Perks formally became Walker’s legal and financial adviser, but this probably dates from at least as early as the negotiation during 1885 for Walker to take on the contract for the Buenos Aires harbour works. The two had been introduced to one another “in the Spring of 1880” by Sir Edward Watkin.[62] Walker was then building the Dover-Deal railway for Watkin’s South-Eastern Railway Company. Perks had commenced working on a series of tasks for Watkin from December 1878 and was about to become principal legal adviser to Watkin’s Metropolitan Railway.[63] In the latter capacity Perks would have come into regular contact with Walker during Walker’s work on the Inner Circle Completion project (1882 to 1884). During 1881 to 1884 Walker also carried out the contract to build on behalf of an “independent” railway company organised by Perks, a small railway in Kent from Appledore to Lydd, with extensions to New Romney and Dungeness.[64]

The size of the issue of new prefs that the Barry board would be looking to “bed-down” if its Bill was passed had become somewhat larger than the figure of £450,000 that has been referred to thus far. In 1885 the company had succeeded in obtaining from parliament what amounted to a restoration to the authorised Barry railway system of the connection into Cardiff that had been excised in 1884. With this had come a much-needed increase in the company’s authorised capital-raising powers: an extra £90,000 in ordinary shares plus £30,000 additional borrowing powers. That £90,000 of ords was also now earmarked to be cancelled and replaced by the same face value in the new prefs. On top of this there was the matter of those holders of the “first tranche” ordinaries who had defaulted on calls and who the company judged it not to be cost-effective to pursue further through legal process. Such “forfeited” ords were also to be cancelled and replaced by prefs. And the 1887 Bill was seeking authorisation to raise a further £50,000 in share capital, to be in the new prefs. All up, the volume of the new prefs to be issued was eventually settled at £598,760,[65] six times the amount of money the Barry’s 1884 prospectus had sought (not very successfully) to find subscribers for. Once this prefs issue was allotted and at least fifty per cent paid-up, the company would obtain a further element of comfort, via becoming legally able to use the remaining segment of its authorised borrowing powers.

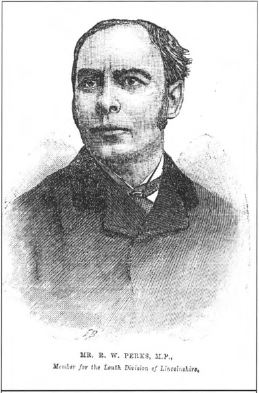

Davies met with Perks in London, in Perks’ office, to discuss the Barry prefs in March 1887. This followed the Barry board meeting of 18 March at which the “question” of the prefs issue had been considered and it was resolved to resume the discussion at the next meeting “and enquiries were to be made in the meantime as to the best method of dealing with the same.”[66] From Perks’ account of this meeting with Davies (their first) it would seem that they did not warm to one another.[67] Perhaps this should come as no surprise. Davies was outspoken about his dislike of lawyers and Perks was a solicitor. Davies believed there were “already too many lawyers in the House of Commons”,[68] and Perks had in August 1886 become the Gladstonian Liberal party’s candidate for the seat of Louth, in Lincolnshire, for the next election to be held there.[69] Davies, following twelve years as a Liberal MP, had broken with Gladstone over the question of Irish Home rule, had stood in July 1886 as a Liberal Unionist and had lost his seat of 12 years to his Gladstonian Liberal opponent (a lawyer). Perks was a supporter of Gladstone’s Home Rule policy and had published a pamphlet on the issue.[70] Soon after the Davies-Perks meeting, Perks found from his City contacts that when approaching other would-be buyers for the Barry prefs, Davies was offering more attractive pricing terms than he had put to Perks.

When the Barry board resumed consideration of the question of the prefs issue on 15 April 1887, the approach favoured by Davies did not involve participation by Perks, and appears to have required that the prefs be subscribed for at less than their par value by a group described as Davies’ “friends”. John Cory advocated a quite different approach and: “reported that his friends were prepared to take the whole of the Pref shares at par and without commission.”[71] This group Cory was referring to was coordinated by Perks. Both John Cory and Lewis Davis had known Perks for many years through their positions as active members of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. Perks’ father, George T. Perks (1819-1877) had been a distinguished Wesleyan minister, secretary of the Wesleyan Missionary Society from 1867 to his death, and elected president of the Wesleyan Conference in 1873. From the commencement of lay representation at the Wesleyan Conference in 1878, R.W. Perks was one of the elected representatives and active in the governance of his church. Cory and Davis were also Liberals and supporters of Gladstone’s Home Rule policy. During the same time that the Barry board was working on resolving the prefs question, Perks ─ acting as “secretary” to a committee of 18 distinguished Wesleyan Methodist laymen ─ was conducting a postal “opinion poll” on the views of Wesleyan lay conference representatives on the Home Rule issue. The results were published in the Times of 3 June 1887. Two of the listed 18 committee members were John Cory and Lewis Davis.[72]

The offer from Perks to bed-down the whole prefs issue at par (and with zero commission) clearly made it untenable for the Barry board simply to accept the Davies preferred approach ─ which would obtain a smaller total volume of capital (after costs of issue) to put towards the construction programme, widen the company’s remaining funding-gap problem, and all-in-all weaken the financial position of the company’s ordinary shareholders as compared with saying yes to Perks. But to Davies and the die-hard Davies supporters on the Barry board, the prospect of seeing the voting-power of the entire prefs issue going into the hands of parties who might use that voting power against them would not have been welcome. Davies’ views as to the proper role of partners in business ventures led by him have been referred to above. He seems to have held similar views re the proper role of railway company shareholders. In 1879, amidst a good deal of acrimony, Davies had resigned as a director of Cambrian Railways, complaining that:

[This Company’s stock] is held for the most part by Bankers, in large amounts, handy for voting purposes … If a man is to be a member of this Board he must be a tool to those who sway this large voting power over his head. He must surrender to their dictates, or make way, like myself for another.[73]

It seems likely therefore that the Barry board’s discussion of “the question” of the prefs issue on 15 April 1887 was a tense affair. It is possible that the Perks offer was designed with the serious intent of paving the way for a shift in control of the Barry enterprise away from Davies. It is also possible that it was what Australians call an “ambit claim”, designed to flush-out a counter-proposal and set the scene for a more focussed negotiation. If it was the latter, it succeeded. The board seems to have agreed to allow Davies some time to consult with his “friends” about how many of the prefs they would be willing to buy at par, either directly or via underwriting an offering to the smaller Barry shareholders. Davies must have indicated some confidence in being able to place between a third and a half of the total issue in this way. The directors agreed to offer the remainder (between £300,000 and £400,000 of the prefs) to the Perks group, with a commitment to pin down the precise number within a month. Prior to the next board meeting on the normal timetable (13 May), an additional meeting would be held with Perks to attend, to progress negotiations on the deal (27 April 1887). Between the Barry’s board meeting of 15 April and its meeting of 13 May this half-way-house approach to the placement of the new prefs was settled and agreed upon. Perks took responsibility for placing £300,000 (the nearest round number to half of the whole issue), and would receive half of one per cent commission. He was paid this £1,500 on 19 August. The “David Davies and friends” group, together with any interested small Barry shareholders, would take up the remainder. And it was agreed that Perks would become a director of the Barry company.

The fact that Perks was paid £1,500, the full half per cent of £300,000 signals that prefs taken up by John Cory and Lewis Davis (£50,000 and £30,000 respectively) were deemed to be part of the Perks segment of the issue, and additional to the figure of £220,000 reported in the Barry board minutes of 13 May 1887 for the number of Perks “had agreed to accept”. The principal members of the group taking up Barry prefs accepted through Perks are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Members of the Perks group taking-up Barry prefs in June 1887

| William Mewburn (senior) | £120,000 |

| J.L. Barker and Wm Mewburn jnr | £48,000 |

| John Cremer Clarke | £10,000 |

| Samuel Hollis Perks | £5,000 |

| Star Life Assurance Society | £25,000 |

| Sir William McArthur | £5,000 |

| W.W. Baynes | £5,000 |

| Sum of above | £218,000 |

The first four entries in Table 1 are members of Perks’ family. William Mewburn senior (1817-1900) was Perks’ father-in-law. After a successful career as a stockbroker on the Manchester Stock Exchange he had retired to live at Wykham Park, Banbury around 1869. John Lees Barker (1843-1924) was the son of Mewburn senior’s partner on the Manchester Stock Exchange and had married Mewburn’s second oldest daughter. After both founder partners had retired, the Manchester stock exchange firm of “Mewburn and Barker” was the partnership of J.L. Barker and William Mewburn junior. John Cremer Clarke (1821-1895) was the father-in-law of William Mewburn junior. He was Liberal MP for Abingdon from 1874-1885. In 1884 he became one of the founder directors of the Blackpool Railway Company. Perks had been the solicitor responsible for steering that company’s Bill through Parliament.[74] S.H. Perks (1830-1910) was a cousin of Perks’ from the much wealthier Wolverhampton branch of the Perks family. Although the two were not very closely related cousins, (R.W. Perks’ great-grandfather George (1752-1833) having been the brother of the grandfather of S.H. Perks), the families had remained closely connected. Edwin Hollis Perks (the eldest son of S.H. Perks), fresh from completing an Oxford B.A. commenced articles to qualify as a solicitor in the firm of Fowler, Perks and Co in March 1887. At sometime during mid-1887 S.H. Perks moved his home from Wolverhampton to Chislehurst in Kent, and thus became a near neighbour of R.W. Perks, who had lived there since his marriage in 1878.

The last two entries in Table 1 are closely associated with entry five. Sir William McArthur was chairman of the Star Life Assurance company from March 1872 until his death in November 1887. W.W. Baynes was at this stage company secretary of the Star, later becoming a director. William Mewburn senior was deputy-chairman of the Star from 1871 to January 1888, when he was elected to succeed McArthur as chairman. Perks’ legal partner H.H. Fowler, who later became Lord Wolverhampton, was also a director of the Star. [75] The support from the Star Life Assurance company for the Perks syndicate’s agreement with the Barry board went further, however, than the company’s direct take-up of prefs shown in Table 1. Minutes of meetings of the Star board of directors have survived and are now in the archives of Zurich Financial Services Ltd in Cheltenham. On 25 May 1887, the Star board discussed a letter from Perks applying for the company to advance £90,000 to David Davies at 4½ per cent interest, the loan to be secured on £90,000 of preference shares. The application was approved. £90,000 corresponds to the exact number of prefs which Davies personally subscribed for in the Barry issue. The fact that Perks and the fellow members of his syndicate went out of their way to help Davies finance his own take-up of almost one-sixth of the total prefs issue seems to represent a tangible message from them to Davies (and his allies on the Barry board) that their intent was not a matter of seeking to take control of decision-making within the Barry company. It may also have been done with an eye to increasing the personal financial incentive facing Davies to make the company a “winner” for all its shareholders.

The Star’s directors may have been predisposed to agree to taking their company into Perks’ syndicate for the Barry prefs by the proceedings at the Star’s annual general meeting on 9 March 1887. Reporting that the earnings rate on the company’s assets had fallen from 4.58 per cent the preceding year to 4.35 per cent, McArthur said: “It is most difficult at the present time to obtain securities of the high class to which we are limited, to pay 4 per cent.” A Mr Griffiths “in a speech of considerable length” criticised the way the company was being managed, arguing that it was “not progressing … that investments should yield a higher rate of interest … the directors should make an effort to reduce expenses …”. Griffiths put himself forward for election to the board. The directors successfully blocked this. [76] But when approached by Perks and sounded-out by him regarding his ideas for the Barry company, the Star’s directors may have felt the time was ripe for a somewhat less conservative approach to the company’s investment portfolio.

The 1887 Barry Act received Royal Assent on 23 May. The directors called a special general meeting for 17 June to obtain shareholder authorisation for the prefs issue. A circular dated 13 May had already been sent out to Barry shareholders inviting them to subscribe for the new prefs “on or before 19 May 1887”, and to lodge a £1 deposit for each £10 share applied for.[77] Immediately before the special general meeting, the board met and elected Perks a director of the company.[78] Immediately after the special general meeting, the board reconvened and approved allotments for the entire prefs issue (£598,760) that had just been authorised. Even with this pace of action, the company faced a severe cash shortage. The terms of the prefs issue included the standard provisions that each calling up of capital on them would be for no more than £2, and such calls would be spaced at least a month apart. But a meeting of the Barry board’s finance subcommittee on 21 May decided that the company would need at least £100,000 of the prefs to be paid in full by shortly after the end of July. It was resolved to send a letter to “proposed allottees” asking whether any of them “would care to pay in full.”[79] This problem was resolved. But it helps underline the extent of the financial stress the Barry company came under during early 1887, up until the agreement with the Perks syndicate was reached. And word of that stress had no doubt spread. On 5 March 1887, the Railway Times reported that the company’s half-yearly meeting had been held on 18 February in Cardiff but added: “This company declines to furnish us with a copy of the directors report and accounts, consequently we are unable to given an abstract of the same.”[80] Six months later, the Barry board appear to have become much more relaxed about providing the railway press with standard reporting information.[81]

Safely bedding-down the Barry prefs issue during April to June of 1887 and then starting to call the money in brought stabilisation to the company’s financial position by August of that year. On the other side of the ledger there had been some further increases to the likely all-up costs of getting the enterprise into a position to commence serious revenue-earning. The Barry board meeting of 18 February 1887 had agreed to two new contracts with T.A. Walker: one for £47,500 for breakwaters at the dock entrance; and one for £82,000 to build the railway connection to Cardiff authorised under the company’s 1885 Act. The preceding board meeting had approved higher costs for Walker’s work on the Wenvoe tunnel where the excavation was through “harder ground” than allowed for in the original contract. Walker attended the October 1887 board meeting and complained about “delays in the delivery of plans and … frequent alteration of plans.” The board minutes record these various decisions to accept higher construction costs or to authorise the engineers to come to various supplementary agreements with the contractors, but it does not seem to have been until December 1887 that the board tried to pin down the overall picture. The figure Wolfe Barry gave for his “total estimate of the works etc.”, was £1,662,300. This was £368,230 higher than the original 1884 parliamentary estimates, although £99,000 of this is Wolfe Barry’s figure for the railway connection into Cardiff ─ not included in the 1884 Act. At this stage the Barry company’s authorised capital-raising powers totalled £1,570,000 (£1.19 million in shares plus £380,000 in borrowings). If the pre-Perks Barry board had been expecting that the capital powers in the company’s 1887 Act would enable them to complete the construction phase of the enterprise, it would have been at this point that any remaining doubt about that would have ended. If the company did not obtain the requisite increase in its capital-raising powers in the round of Private Bills going through Parliament during the first half of 1888, it would exhaust its capacity to go on paying its construction costs some time during the second half of that year.

It is impossible to believe that this would have come as a surprise to Perks. Of every £100 of construction costs the Barry company incurred, about £85 was payable to T.A. Walker. With his depth of experience, Walker may have been in a better position than Wolfe Barry to make accurate and up-to-date assessments of the likely total construction costs bill for the Barry project. He would no doubt have communicated this information to his financial adviser, Perks. And whereas Wolfe Barry may have faced incentives to think in terms of figures which incorporated an “optimistic” view of containing cost blow-outs on the project, it was clearly in Walker’s interest to think in terms of the company’s capacity to pay its bills under more “pessimistic” scenarios. Two conclusions emerge if this is accepted. First, the Perks group expected, when they took up half of the Barry prefs issue in mid-1887, to be called upon to help the company with further significant capital raisings before the Barry enterprise became revenue-earning. Second, the Perks group were aware that a substantial enhancement to the company’s authorised capital-raising powers would be needed in the next parliamentary session.

For Davies and his allies on the Barry board there was probably no discomfort in the prospect of Perks and his group helping the company raise debt-funding by underwriting debenture issues. Debenture holders have no “voice” in the affairs of a company as long as their interest is being paid in full and on time. But the prospect of Perks and his group “helping”, in any sizeable way, with the placement of further issues of share-capital in the Barry company may have been regarded as worrying. If so, one would expect Davies and his group to react by: (a) pressing a “minimalist” view of how much additional share capital the company needed to raise; (b) seeking to delay such raisings as long as was compatible with maintaining the pace of work on the enterprise’s construction programme; and (c) trying to maximise the proportion of any new issues taken up by the company’s original ordinary shareholders, minimise the proportion going to the Perks group, and sequence things so issuance to the non-Perks group would precede issuance to the Perks group. The actions of the Barry board from late 1887 to the opening of the dock suggest the pursuit by Davies and a majority of his colleagues of this type of three point approach.

It is possible that Davies genuinely believed that with his hand at the tiller, construction costs could be reined-in and the dock opened by late-summer 1888, so that the company’s needs for additional capital-raising powers to use during 1888 were modest. Alternatively it may have been his view that the projection of an image of boundless and imperturbable confidence was his over-riding duty to the Barry shareholders, and that any public acknowledgement of a slide in the construction timetable, or a need for significantly greater capital-raising powers would set off an adverse chain reaction in investor and creditor perceptions (and behaviour). At the Barry company’s half-yearly general meeting held in Cardiff on 19 August 1887, Davies took the chair (Windsor being absent) and told the shareholders that the work of constructing the company’s dock and railways: “although a very arduous undertaking was proceeding in a most satisfactory manner and there was little doubt that all the work would be completed and the dock opened by September next year.”[82] An interesting indicator of Davies’ views on the potential damage to the Barry Company from any relenting in this projection of confidence came twelve months later.

On 24 August 1888, at the request of the Barry’s company secretary G.C. Downing, the Times published the following letter:

Sir. In your report on the half-yearly meeting of the Barry Dock and Railways company you have stated ‘no doubt the dock would be opened next year.’ This statement is inaccurate and calculated to be extremely injurious to the interests of the company. The shareholders were clearly informed at the meeting by the chairman and the deputy chairman that the directors confidently anticipated the opening of the dock before the close of the present year.[83]

A threat of legal action seems clear here. In fact, Downing (together with Szlumper, the engineer for the northern part of the Barry railway) had taken a libel action against the proprietors and publishers of the Western Mail, Evening Express and Weekly Mail over a series of articles on the Barry company published during December 1887. The jury had found for the plaintiffs and awarded damages of one farthing each.[84] If Davies had pursued this August 1888 matter against the Times, it would have been interesting to see his explanation of the directors’ confident anticipation re the dock completion timetable. The dock opening did not occur until July 1889.

Returning to the question of additional capital-raising powers to be pursued in the 1888 parliamentary session, this was discussed by the Barry directors at the board meeting of 16 December 1887. It seems from the board minutes that higher figures were talked about, but the decision made was to seek only £90,000 additional share capital plus £30,000 additional borrowing powers. This would have increased the company’s total authorised capital raising powers to £1.69 million. Set alongside Wolfe Barry’s estimate for completing “the works etc.”, of £1.66 million, plus an allowance for other costs not included in that figure (legal costs, land, interest etc. ─ see Section I above) this can only be interpreted as an ambitiously “minimalist” figure. At the board’s next meeting (20 January 1888), retrospective approval was given to a substantially greater figure having been written into the company’s Bill as lodged to meet the parliamentary deadline. The amended figure was £210,000 additional share capital plus £70,000 additional borrowing powers. The board minutes provide no explanation of this change.[85] The amended figures, when the 1888 Barry Act received Royal Assent in August, increased the company’s total authorised capital-raising powers to £1.85 million. By the end of 1888, even this figure was looking “tight”, and for the company’s 1889 Bill, the directors agreed to seek authorisation of a further £300,000 of share capital plus £100,000 of borrowing powers. The upward revision to the figure agreed at the December 1887 board meeting does suggest, however, that at least some of the Barry directors had ─ soon after that meeting ─ second thoughts about the balance of pluses and minuses in trying to get through the whole of 1888 and the first six months or so of 1889 with no margin for comfort (or with a negative margin) in terms of capital needs versus capital-raising powers.

Assuming that Davies had been comfortable with the “minimalist” decision made at the December 1887 board meeting, he may not have been particularly happy about this process of “second thoughts” among directors who had originally supported the “minimalist” stance. But Davies remained on the board and remained the company’s de facto managing director. Perhaps this was a rare occasion in the record of Davies’ life that a contrary view to his own on a business issue had been argued to him, and he had gracefully accepted the wisdom of altering his own position. Whatever the process was that led to the Barry board decision of December 1887 being so substantially amended, it seems certain that this would have come as a great relief to T.A. Walker. The prospect of having to make a choice at some stage during 1888 between continuing his work on the Barry project in return for payment in IOUs, or halting work and trying to redeploy his equipment and key personnel to other projects, would not have been welcome for Walker. And more particularly so because he was facing exactly the same worry on the Preston docks project at this time.

Walker had tendered to construct new docks for Preston Corporation a month or so before he tendered for the Barry project. On 3 September 1884, Preston Corporation accepted his tender (£456,600 11s 2d), and the first sod was turned on 11 October 1884. At Preston, as at Barry, the dimensions of the projected dock were substantially increased from those in the parliamentary plans. In this case to 40 acres from 30 acres. And also as at Barry there were other cost escalations. By September 1887 the Preston Corporation had spent £723,627 on the project, faced an estimated total cost figure of £1,171,627 and had only £662,244 of authorised borrowing powers for the project.[86] In the 1888 session of Parliament, the Preston Corporation sought additional borrowing powers and retrospective approval for its actions in spending a greater-than-authorised amount on a bigger-than-authorised project. A protracted parliamentary process ensued. In July 1888 Preston Corporation was authorised to borrow enough money to pay what it then owed to Walker (£40,000). Work on the project was then halted and Walker’s men and equipment withdrawn. After further process, including a Board of Trade Commission of Inquiry into the scheme, Preston Corporation obtained powers to complete the project and the Walker enterprise resumed construction work in July 1890.[87] In December 1887/January 1888, with these disruptions looming over his contract in Preston, it must have come as welcome news to Walker that the Barry board had resolved to amend its earlier position, and would now seek a more realistic increase in the Barry company’s authorised capital-raising powers in the 1888 Parliamentary session.

Perks may have been expecting that there would be a significant role for him and his group in the placement of the £210,000 of new Barry shares to be created under the 1888 Barry Act. If so, he was to be disappointed. In August 1888, as soon as the new powers had been secured, the Barry board resolved (subject to shareholder approval) to use the powers and create £210,000 in new “second preference” shares, and to offer these to the company’s ordinary shareholders on a pro-rata basis at £12 per £10 share (to be called-up incrementally over time). The offer of these second prefs was not to be made to holders of the first prefs, only to ordinary shareholders, and only on a pro-rata basis. Although Perks and his group may have been buying parcels of Barry ords as they came onto the market, the terms of this offer of second prefs would clearly have focussed it away from the newcomers and onto the company’s early core supporters and their associates. Like the first prefs, the second prefs would receive 4 per cent interest (paid from the company’s capital) until the dock and railway system became revenue-earning, and from that point onwards would be entitled to dividends (from profits) up to a cap of 5 per cent per annum ─ with these taking priority over the ordinary shareholders receiving any dividend. In the event that the company’s profits could not cover a 5 per cent dividend on all its preference shares, the first prefs would be paid their 5 per cent in priority to the second prefs receiving anything.

At the Barry shareholders’ meeting called to approve the arrangements described above, Davies presided (in Windsor’s absence) and gave another of his performances that focussed more on building feelings of confidence and strength among his audience than on a conveying of accurate information. The Times reported Davies as saying that “All the shares are already subscribed for”, and as offering “to take all of them up [himself].”[88] When the Barry board met on 21 September 1888, it was reported that of the 21,000 second prefs offered to the company’s ordinary shareholders, 12,069 had been accepted “and it was resolved to retain the unaccepted shares with a view to selling them later on at an increased premium.”[89] It is hard to reconcile this with Davies’ words at the shareholders meeting. In the Herapths report of that same shareholders meeting, Davies is reported to have said: “the actual construction of the dock had cost just as little as if the smaller scheme had been adhered to. This was owing to the more favourable nature of the foundations.”[90] This was another fairy story. It would seem that Davies had been very keen to maximise the take-up of the second prefs offer among the company’s ordinary shareholders.

By January/February 1889, takers had been found for the whole of the £210,000 second prefs issue. It is not clear from the Barry board minutes what the processes for this were, but none of these shares appear to have gone to Perks or his group. Interestingly though, Perks did once again help Davies by intermediating for him with the Star for the loan of a further £20,000 in February to allow him to take up some of the tail of the issue. This would suggest that Perks was not entirely uncomfortable about the way the offer of the Barry second prefs had been “targeted”. And if this was the end of the story of Perks’ involvement in the placement of Barry share issues, it would be easy to take the view that Perks and his group had not wanted to take up significant additional shareholdings in the Barry company beyond their 1887 allotments of first prefs. But at the Barry board meeting of 15 February 1889, the directors agreed that (subject to shareholder approval) they would use the further capital-raising powers being applied for in the 1889 Barry Bill to do two things: create £150,000 of new ordinary shares and offer these to the company’s ordinary shareholders at par; and create £150,000 of third preference shares. Nothing was done about the proposed issue of third prefs until a year later. At the board meeting of 12 March 1890, which Perks did not attend, it was agreed that: “Mr Cory was to ascertain … what offer Mr Perks or his friends would make.”[91]

The upshot was that when allotments of these third prefs were made at the Barry board meeting of 16 May 1890, there was a significant take-up both by members of the 1887 Perks group and by other close associates of Perks ─ including £50,000 allotted to “W. Mewburn

and others”,[92] £3,000 to S.H. Perks, and £2,000 to H.H. Fowler. It is possible that their views on investing in the company may have altered since August 1888, with the dock and railways now completed and in operation, but this does create some doubt as to whether they had been “willing abstainers” from the issue of second prefs in 1888. Also, for the Davies camp to allow the Perks group into the third prefs offer in this way would match-up with the possible “three-point” agenda for maintaining the Davies group’s control of the company as hypothesized earlier.

Between the placement of the first issue of Barry prefs in April/May 1887 and this placement of third prefs almost exactly three years later, Perks was involved in two rounds of loan-capital raisings for the Barry enterprise. The first was during early 1888 and involved using-up the company’s remaining authorised borrowing powers from its 1884, 1885 and 1887 Acts, totalling £205,000. At the Barry board meeting of 17 February 1888 it was resolved that “Mr Perks was authorised to offer £150,000 thereof to his friends at £105”[93] (i.e., £105 for each £100 of “principal” or “face value”). It appears that the Mewburn and Barker stockbroking firm in Manchester agreed to place £100,000 of these debentures with their clients on these terms and that the other £50,000 were then placed through the Cardiff firm, Messrs Lyddon. On 20 April 1888, the Barry board resolved to issue the remainder of the £205,000 “to ordinary shareholders at £110”.[94] On this occasion, the ordinary shareholders insiders accepted a worse deal than the Perks group outsiders. But at this stage the company was very “capital hungry”, and its 1888 Bill was still held up in the parliamentary process. The insiders may have viewed the £5 gap as a tolerable expedient for raising a little more cash than the parliamentary powers on “face value” indicated.

The second of the loan capital raisings Perks was involved in came twelve months later. Before the company could use the additional £70,000 of borrowing powers obtained in the 1888 Barry Act, it was necessary that the new shares created under that Act should be at least half paid up. The call on the Barry second prefs that would satisfy this requirement had set 20 April 1889 as the due date for payment, and the Barry board acted rapidly to take advantage of becoming able to raise more debt-funding. At the board meeting of 16 April, the directors resolved:

That Mr Perks be authorised to dispose of £50,000 debenture stock providing he could get more than £110 [per £100 face value] for same and that in the event of his not succeeding … during the next fortnight a circular be issued offering the debentures to shareholders at £110.[95]

The second part of that resolution suggests the directors were keen to get the money from this debenture issue into the company rapidly. In April 1889, the Barry board were hoping to open the dock and commence full operations across the company’s railway system in mid-June. This later slid to 18 July.[96] Clearly the pressure to raise cash to meet costs of construction work, of equipment, and of preparation for operations generally, remained strong during this period. It is not clear from the Barry board minutes how many of this tranche of debentures were placed through Perks, but the board meeting of 21 June recorded that by then £56,820 had been paid-up on the debenture issue, suggesting the offer had gone ahead smoothly and rapidly.

Total spending by the Barry company from its inception up to 30 June 1889 was £1,901,216.[97] Raisings of capital-funds organised through Perks and his group (£300,000 of first prefs plus the two debenture issues) contributed almost a quarter of the total cash required to cover that spending. In addition Perks helped Davies raise £110,000 of the money which he put into the enterprise during the last two years of this period, by arranging for loans from the Star Life Assurance Society. If we focus on the period from Perks and his group joining the company through until June 1889 and count in those Star loans to Davies, the arithmetic is that Perks raised around half of the money required to carry forward the enterprise’s capital spending during that period. This represents a considerable role played by Perks towards the eventual success of the Barry enterprise. During 1887 and 1888, many of the original core shareholders in the company (and Davies in particular) were being squeezed between depressed conditions in the coal market and the rising costs of the Barry construction programme. The part played by Perks and his group allowed the company’s original core shareholders to maintain control of the Barry enterprise and implement their original vision for the project whilst maintaining continuity in the pace of the construction programme.

The capital funds raised through Perks and the apparent willingness of his group to contribute more, combined with the continuing support of the company by its earlier core shareholders removed downward pressure on the Barry share price, and rendered the company credit-worthy through the remainder of its infrastructure building phase.

From mid-1889 a significant shift in the economics of the Barry company becomes increasingly apparent. And there is more to this than the shift from constructing the Barry rail and dock system to operating that system. The nadir in the pit-head price of coal in Glamorgan was 1886 with 5.12 shillings per ton as the year average. And for 1887 it remained very low at 5.31. In February 1887, the Economist reported: “the prices of coal are so low as to be quite unremunerative to all but the most favourably situated collieries.”[98] In 1888 the price recovered to 5.84, the same as the level for 1885, but still below the 6.23 and 6.25 of 1883 and 1884 when the Barry project had been promoted. During 1889, however, a much stronger recovery in demand for coal built up with the price rising to 7.96 for the 1889 year average and 10.29 for 1890 (more than double the 1886 level). Total Glamorganshire coal output in 1889 was 19.1 per cent greater than in 1886 and increased a further 5.6 per cent in 1890.[99] The impact on colliery profits was substantial. The gross profits of Davies’ Ocean Collieries were £12,511 in 1886 and no dividends were paid. In 1890 gross profits were £255,056 and dividends of £184,000 were paid. Unfortunately the figures for 1889 are unknown. But the price and volume statistics would suggest that they were on the way towards those spectacular 1890 numbers from the 1888 gross profit figure of £28,540.[100] Not only was the financial squeeze on the colliery owners among the Barry company’s core shareholders abating during 1889, but the prospects were improving for a healthy demand to ship coal across the company’s new rail and dock system.

When the Star had originally agreed to lend Davies £90,000 in May 1887, it was to be a fixed-term 5 year loan. By early 1890, with the strength of the coal trade flowing through into his personal finances, Davies approach the Star to make early-repayment arrangements. In May the Star board agreed to receive repayment of the full £110,000 of the two Davies loans on an eighteen months timetable.[101] When Davies died in July 1890 the gross value of his estate was sworn at £404,424.[102] Three years earlier, with the coal trade much weaker, the value of Davies colliery assets would have been much lower. Despite the public image that Davies projected of himself as being sufficiently wealthy to pay for the completion of the construction of the Barry dock and rail system himself, if that became necessary, it is hard to see how this could possibly have been true as at late-1886/early-1887. Even after making allowance for contributions Davies’ allies on the Barry board seem to have been willing to put in, that remains so. In late-1886/early-1887 Davies, (and the Barry company’s other core shareholders) needed significant outside funds. And they needed an “acceptable” outsider to help them secure such funds on terms and conditions tolerable to them. That was the principal service that Perks supplied, and one of those conditions was clearly that he join the board of the company ─ to watch over the interests of his group of “outsider” providers of capital until the enterprise was operating successfully on a sustainable and prosperous basis.

As part of this role, Perks navigated the Barry company through the processes required to have its shares approved to be officially traded on the London Stock Exchange. The key step required for such approval was the appointment by the Stock Exchange committee of a “special settlement day” or SSD. In March 1887, before the Perks group had come on board, Davies had arranged with Messrs Greenwood and Co (members of the London Stock Exchange) to lodge an application for an SSD. The Times of 28 March 1887 reported that this application had been lodged.[103] But at the Barry board meeting of 20 May 1887, after the agreement with the Perks group had been made, the directors agreed to halt the SSD application process. It was not resumed until over 18 months later. There are two reasons for this delay. One is that Perks had no reason to be in a hurry on this. When the Perks group agreed to go into the Barry company in 1887, on the terms they did, they would have been aware that this was an investment that needed patience. For Barry securities to become known, and regarded as a “good buy” among the broader ranks of the British “retail” share-buying public, the company would need to be operating its rail and dock business, operating it profitably, and (ideally) giving tangible evidence of the latter by declaring healthy dividends. Looking forward from the perspective of April/May 1887, the earliest time that this might be expected to fall into place was probably 1890. If by that time there was an active market in the company’s shares on the London Stock Exchange, this would help members of the Perks group exit from their Barry paper smoothly and expeditiously once they made a decision to do so.

At the Barry board meeting of 14 December 1888, Perks resurrected the question of a London Stock Exchange quotation for the company’s securities. The directors agreed to revive the matter and to put carriage of it: “in the hands of Mr Perks and Mr Downing”. At the Barry board meeting of 18 January 1889, Perks reported that he had met with Alexander Henderson, the managing partner of Messrs Greenwood and Co., and the Barry directors resolved to accept Henderson’s charges for carrying forward their company’s SSD application. These amounted to a fairly hefty 750 guineas.[104] On 23 January Perks wrote to Henderson requesting that he trigger the process and he did this on 29 January.[105] The application that was lodged covered the company’s ordinary shares, its first prefs and its second prefs but not its debentures. As the “tail” of the second prefs issue was at just around this same time being allotted among the company’s ordinary shareholders (see above), this may explain why Perks was able to garner majority support on the Barry board to revive the SSD application (and accept Henderson’s charges) at this time.[106]

It is at this point that the second reason for not reviving the process with the London Stock Exchange sooner becomes clear. The Davies approach to running a company’s financial paperwork does not seem to have been in harmony with the requirements of the Committee of the London Stock Exchange for approving official trading in a company’s securities. One of those requirements was that a company should allocate to each of its shares a unique “identifying number” that would not change as that share changed hands. Each share certificate issued by the company should display clearly the identifying numbers of the shares it covered. The intention was clearly to provide for a “paper-trail” to allow checking the authenticity of any would-be seller of shares being entitled to receiving payment for those shares. It is hard to see anything untoward with such a requirement. But when the Stock Exchange Committee considered the Barry application, they found that the company’s shares were not: “in a condition to be admitted to the official list owing mainly to the way in which they were numbered and issued. Some numbers appeared no less than three times over, and there were three sets of certificates.”[107] On top of this there were some arithmetic problems in the statutory declarations signed by Davies and Downing to support the SSD application.[108]

The solution to the certificates problem that Perks implemented during 1889 involved converting the company’s “shares” into “stock” (which for all practical purposes is exactly the same thing) and replacing the Barry share certificates with new (and Stock Exchange compliant) stock certificates. This required formal shareholder approval at a general meeting, was no doubt costly and time-consuming to administer, and probably raised some eyebrows as to how it was that the company’s affairs had been managed so deficiently in the first place ─ three good arguments for postponing the matter in May 1887. Perks probably became aware of the Barry certificates situation quite early in his relations with the Barry company. He and Alexander Henderson knew each other well. At the beginning of 1887 the two had worked together on an innovative arrangement to raise a form of bridging-finance for T.A. Walker’s construction work on the Buenos Aires docks.[109] They also worked together on some of the financial arrangements associated with the contract Walker entered into in April 1887 to construct the Manchester Ship Canal.[110] An SSD for the Barry’s ordinary shares and first prefs was eventually approved for 15 October 1889. An SSD for the second prefs was not approved. It may be that the Stock Exchange Committee harboured concerns as to whether the entire second prefs issue had in reality been allotted and paid-up in the way the Davies and Downing statutory declaration represented. It may be that since the Perks group had been excluded from participation in the second prefs issue, Perks was less vigorous in his pursuit of an SSD for those shares.[111] By the early part of 1890, there is evidence of the Perks group making use of the newly established London Stock Exchange trading in Barry shares for disposing of some of their holdings. Perks himself sold 400 of the company’s £10 ordinary shares during February/March, probably making a capital gain of about 100 per cent. During the same period W. Mewburn disposed of 40 separate parcels of first prefs, a total of 3,900 of the shares.[112]

The contribution of Perks to the Barry company during his three years as a director was not confined to his role in securing capital funds for the enterprise and providing for improved secondary-market trading arrangements in the company’s securities. But those are undoubtedly the areas where he made his most significant contributions. From the board minutes it appears that Perks provided the company with the benefit of his expertise in railway law on a regular basis, that he participated in various negotiation processes ─ including with the GWR, and with the promoters of the Vale of Glamorgan railway,[113] and that he provided an important interface between the Barry company and T.A. Walker. This interface situation put Perks in a delicate position. In its absence Perks would still have faced the difficulties of navigating a path between the desire of the Davies group to maintain control of the Barry enterprise so as to implement their original vision for the project, and the sensitivities of his own investor-group to the risks of being “exploited” by the Davies group. The Walker interface compounded the complexities of Perks’ task. Should the Davies group and members of Perks’ own group view his role as Walker’s legal and financial advisor as a bonus, helping ensure harmony between Walker and the Barry company, and mutually beneficial outcomes from the Walker contracts? Or should they worry that Perks’ primary loyalty might be to Walker’s interests, and that he might incline towards the company paying more for harmony with Walker than they viewed as warranted? With ordinary shareholders to rank behind first prefs holders in distributions from the company’s profits, this latter worry was probably more pressing for Davies and his group than for the members of Perks’ own investor-group. The next section discusses how these tensions emerging from Perks’ professional relationship with Walker intensified during the later part of Perks’ time as a director of the Barry company.

Notes and references

[62] Denis Crane, The Life of Sir Robert W. Perks, Baronet, MP., Robert Culley, London, 1909, p. 74.

[63] See Owen Covick, “Mapping the career of a businessman who was an independent operator and who left no substantial papers: the case of Sir R.W. Perks 1849-1934”, paper presented to the 2005 Conference of the Association of Business Historians, Glasgow: page 4 and accompanying footnotes (p. 39).

[64] ibid, pp. 10-12.

[65] This means that of the £600,000 (face-value) “first tranche” shares, £8,760 had been forfeited. When the fortunes of the company improved and the ordinaries were trading at well above face-value, those whose shares had been “forfeited” may have regretted that. In January 1889 Davies and the Barry secretary G.C. Downing signed statutory declarations in support of the Barry company’s application to the London Stock Exchange for a quotation for 59,505 of fully-paid up £10 ordinary shares. When the Stock Exchange queried the discrepancy, Downing corrected the 59,505 to 59,124 and described the former figure as “an unaccountable error”. Guildhall Library MS 18,000 22B/358.

[66] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[67] Notes for an Autobiography, p. 100-101.

[68] Quoted from an 1875 Davies speech in Herbert Williams, op. cit., p. 157.

[69] Denis Crane, op. cit., p. 170; and N.J.L. Lyons, “Sir Robert Perks, Liberal MP for Louth, 1892-1910”, Epworth Witness, vol. 2, pp. 12-14.

[70] R.W. Perks Speech by Mr Perks [On Home Rule for Ireland], E.H. Ruscoe, Louth, undated. This may be the speech which Perks’ cousin John Hartley Perks refers to in his diary entry for 27 October 1886 (Wolverhampton Archives DX/127/2/14)..

[71] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[72] Times, Friday 3 June 1887, p. 5. For an earlier report on Perks’ survey see Times, Monday 9 May 1887, p. 9. For a full analysis see D.W. Bebbington, “Nonconformity and Electoral Sociology, 1867-1918”, Historical Journal, vol. 27 (1984), pp. 633-656. On lay representation at the Wesleyan Conference, see Martin Wellings, “Making Haste Slowly: The Campaign for Lay Representation in the Wesleyan Conference 1871-8”, Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, vol. 53 (2001), pp. 25-37.

[73] Quoted in Herbert Williams, op. cit., pp. 181-182.

[74] See London Gazette 1882, pp. 5262-64 and 1883, pp. 5951-52; and George Dow, Great Central, vol. 2, Ian Allan, London, 1962, chapter 9, “A Railway that Never Was”.

[75] McArthur’s nephew, William Alexander McArthur (1857-1923), was elected to parliament as Gladstonian Liberal MP for the St Austell division of Cornwall at a by-election in May 1887. In August 1890, this nephew married Florence, daughter of J.C. Clarke. W.A. McArthur and his father were listed as members of the committee for the Perks “opinion poll” (see footnote 73), as also were Mewburn senior and H.H. Fowler.

[76] Investors Guardian, 12 March 1887, p. 214. H.H. Fowler is reported as speaking at the meeting in defence of the board and against Griffiths’ criticisms.

[77] A copy of the circular is in Guildhall Library MS 18000 22B/358.

[78] TNA RAIL 23/2. Two vacant seats on the Barry board were filled on 17 June 1887. The other new director was Louis Gueret (1844-1908), a partner in L&H Gueret, coal shippers and patent fuel manufacturers, Cardiff. Gueret had been a Barry shareholder since the first allotments of shares in September 1884. There is no reason to believe he had any association with the Perks group. Prior to 17 June, Perks had purchased 500 Barry £10 ordinary shares and had thus become “qualified” to be elected a director.

[79] ibid. On 3 August 1887, after receiving a letter from Perks, the Star board agreed to pay early, in full. Zurich Financial Services (UKISA) Ltd Archives ST1/5/1/14 Minute 3290.

[80] Railway Times, 5 March 1887, p. 298. A week before, Herepaths had reported Davies informing the meeting about the company seeking power from parliament to convert the ordinaries which they had “kept back” into new prefs and stating “He hoped they in Cardiff and the vicinity would take up the preference shares for they did not want them to be placed in the hands of strangers.” (Herepath’s Railway and Commercial Journal), 26 February 1887, pp. 214-5.

[81] Railway Times, 27 August 1887, pp. 270-271.

[82] Times, 22 August 1887, p. 11.

[83] Times, 24 August 1888, p. 9.

[84] Times (Law Reports for June 1), 2 June 1888, p. 6. This report mis-spells Szlumper’s name as Zshemper. The offending newspaper articles had “charged the plaintiffs with gross blundering, with carelessness … which put [the Barry company] in a fix, and then making flimsy excuses … to delude the shareholders and the confiding public.” (loc cit).

[85] TNA RAIL 23/2. Perks did not attend the January board meeting. But at the December meeting, which he did attend, he had been appointed as an additional member of the board’s Parliamentary Sub-Committee.

[86] Jack M Dakres, The Last Tide: A History of the Port of Preston, Carnegie Press, Preston, 1986, pp. 125-6, 138 and 145.

[87] ibid, pp. 149-166. T.A. Walker died in November 1889. The project was completed by the Trustees/Executors of his deceased estate. The Walker Estate is discussed further in Section III of the present paper.

[88] Times, 6 September 1888, p. 10. The special meeting was held on 4 September in Cardiff.

[89] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[90] Herapaths, volume 50 (1888), p. 1013.

[91] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[92] The Board minutes of the Star record the directors agreeing on 19 March 1890, in response to a letter from Perks, to apply for £50,000 of the Barry third prefs (ST1/5/1/15 minute 3759), so this parcel is probably Mewburn and others as trustees (or nominees) for the insurance company. The Star minutes record half this parcel being sold in June 1893 at a price of £14.50 per share (ST1/5/1/17 minute 4652). The purchase price had been £12.

[93] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[94] ibid. The placement through Messrs Lyddon suggests that the Perks group wished only to take £100,000 of the £150,000 offered.

[95] ibid.

[96] ibid. The board meeting of 15 March 1889 resolved that the dock be opened on 18 June. Passenger operations on the company’s line to Cardiff had commenced on 20 December 1888, possibly as a “face-saving” move in the wake of Davies’ previous strong statements about the Barry system being completed by the end of that year. Perks opposed the early opening of the Cardiff branch, and the dissenting votes of Cory, Davis and he were recorded in the board minutes for the October 1888 meeting.

[97] This is the figure from the company’s half-yearly accounts (Financial Times, 27 August 1889, p. 1).

[98] Economist, 19 February 1887, p. 29 of supplement. Note that this is a statement about the position across the UK as a whole. The Glamorgan coal price figures are from R.H. Walters op. cit., p. 359.

[99] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 347.

[100] Trevor Boyns, op. cit., p. 166.

[101] Zurich Financial Services (UKISA) Ltd Archives. ST1/5/1/15 minute 3951.

[102] D.S.M. Barry, “David Davies (1818-1890)”, in David J. Jeremy (ed.), Dictionary of Business Biography, Volume 2, Butterworths, London, 1984, p. 22.

[103] Times, 28 March 1887, p. 11. There is no record of this application in the records of SSD applications held by the Guildhall Library in MS 18,000. This may mean that the massive volume of material in MS 18,000 nevertheless represents only applications which eventually were approved.

[104] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[105] Guildhall Library Manuscript 18,000: 22B/358.

[106] Henderson had quoted 250 guineas for each class of securities the application was to cover. The Perks group may have been disappointed that the board had approved application for the second prefs issue which they had been excluded from, but not for the debentures they had helped place.

[107] Guildhall Library MS 18,000: 22B/358.

[108] See footnote 66.

[109] The prospectus offering £800,000 of “trust certificates” in the Buenos Ayres (sic) Harbour Works Trust was published in the Times of 11 March 1887, p. 11, and an SSD was approved for 13 May 1887. See Own Covick, op. cit., p. 23 and footnote 87.

[110] On Walker’s contract for the Manchester Ship Canal, see Ian Harford, Manchester and its Ship Canal Movement, Keele University Press, 1994.

[111] Notice of the SSD approval appeared in the Times, 8 October 1889, p. 12. The second prefs were granted an SSD in September 1891. Neither Perks nor Henderson was involved in that later application process.

[112] The share transfers are recorded in the Barry board minutes (TNA RAIL 23/2). Between the beginning of February 1890 and the end of March, Barry ordinaries rose from £13.75 to £17.50 per £10 share. The estimate of a 100 per cent capital gain assumes Perks bought during the first half of 1887, when his cost would have been a little over £8 per share (see above). Over the same two months the first prefs were essentially steady at around £13.25 (Economist, Investors Monthly Manual, 28 February 1890, p. 79 and 31 March 1890, p. 131).

[113] Eventually the Vale of Glamorgan railway became a de facto extension to the Barry system (see D.S. Barrie, The Barry Railway, pp. 172-4). When the company first attempted to raise funds to build its railway, through a prospectus published in June 1890, the attempt failed. The 1890 prospectus cited the Mewburn and Barker firm as one of five brokers to the issue (Financial Times, 30 June 1890, p. 5; Times 30 June 1890, p. 11).