Chapter 10: Characteristics

A scan of the original unannotated document can be accessed from the HathiTrust Digital Library collection at

The Life-Story of Sir Robert W. Perks, Baronet, by Denis Crane.

[start of page 221 in original pagination]

Chapter X: Characteristics

A WELL-KNOWN writer, of ultra-Radical if not socialistic proclivities, hearing that a Life of Sir Robert was shortly to appear, indulged a little unwonted malevolence at that gentleman’s expense. Discussion elicited the fact that Sir Robert was held guilty of two enormities: he had denounced the preaching in the pulpit of party politics, and, still worse, had ‘made money’!

As the discussion of politics of any sort in religious services is a practice as to the rightfulness or wrongfulness of which even the Christian Church itself is sharply divided, the matter may be dismissed with the single remark that in general no sins are more fearful in theory and more trivial in fact than those attributed to each other by uncharitable Christians.

On the second point there is more to be said. In an age when it is becoming more and more an offence for the individual to hold property

[start of page 222 in original pagination]

at all, it is perhaps natural for certain classes to suspect the morality of money-making. Cynics and malcontents, in particular, may be expected to ask. Can a man grow rich honestly? And as a negative answer is more flattering to the inquirer than an affirmative, it is not surprising, human nature being what it is, that it is the answer commonly given. More observant philosophers, however, are unable to rest in such hasty generalizations, and find that there is a retributive principle at work in the world, whereby on the whole men get pretty much what they deserve. Applied to industrial and commercial life, this rule shows that there is a closer relation between character and industry on the one hand, and prosperity on the other, than the practice of many might lead one to suppose. Nor will the popular plaint about difference of opportunities bear investigation. Such differences certainly exist; but it is notorious that the majority of the world’s great businesses have been founded by men who owed nothing to opportunity, and who had, indeed, in early life to fight against poverty and misfortune; while who cannot point to great houses that have crumbled and fallen, notwithstanding

[start of page 223 in original pagination]

all their prestige and resources, through the irresolution and weakness of those who have succeeded to their management?

In accounting for Sir Robert Perks’s success, however, it must be remembered that he started with some valuable assets — robust health, a well-spent youth, honourable family traditions and a dauntless spirit. We have also seen that as a young man he was of punctual and regular habits, and that he was at work while most young fellows are still abed. It may be interesting to know to what he himself attributes a good deal of his success. ‘I have been asked,’ he once said, ‘how I have contrived to get through such an enormous amount of business. My reply is: by having no arrears; by making up my mind quickly, even though I occasionally make mistakes; and by delegating as much of the detail as possible, while at the same time keeping master of it myself. My counsel to the young fellow of to-day is, first, be extremely abstemious; second, work very hard; third, save all you can, and fourth, pay little attention to criticism. If he asks many people’s opinions and worries himself about what people say, he will have no peace at all.’

[start of page 224 in original pagination]

His own average day is still a busy one. Half-past seven is now his usual hour of rising. Before his duties at the House of Commons detained him abroad till nearly midnight, it was his practice to be in his office at nine o’clock every morning. Even when he resided at Chislehurst he did not depart from this habit for fifteen years. His mornings are divided between his office at Westminster[1] and the City. The rest of the day he devotes to political duties, filling up the intervals with interviews and his books and papers.

In this programme, it will be noticed, there is little place for recreation. This he finds chiefly in change of occupation. A thorough sympathizer with healthy sport and pastimes, he nevertheless holds that excessive devotion thereto is in many cases responsible for lack of business success. The same amount of energy expended in more serious pursuits would, he thinks, yield commensurate returns of a substantial kind. Of course, if the young footballer is satisfied, there is no more to be said; every one to his taste. Only, ‘Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.’

Though opportunities alone do not explain success, where there is character they facilitate

[start of page 225 in original pagination]

and promote it. Some of the openings of which Sir Robert made such excellent use do not to-day exist, or are much restricted. Railway extension in this country, if it has not reached its limits, is fast approaching them. Competition in the professional world is much keener than it was. And there are not so many safe and profitable investments open to the man of modest means. Another point not to be overlooked is that some vocations cannot, with all the energy and industry in the world, yield more than a limited return. The great professions, if they impose heavy initial costs and have heavy risks, offer to the man of talent many opportunities of amassing wealth. But who can say as much of journalism[2], or bricklaying, or painting, or driving a ‘bus? Yet, happily, money is not everything, and every calling has its compensations.

Then, even within the limits of a particular vocation there is scope for discrimination. Some veins are already overcrowded and exhausted, others are practically untapped; and there will always be those who lack the initiative to strike out in the latter. The same weakness obtains in the religious world. Who does not know those who lavish on the resus-

[start of page 226 in original pagination]

citation of effete institutions the care and labour which others give to the launching of a world-crusade or the introduction of the gospel to a continent? Needless to say, Sir Robert Perks approximates to the latter type. Nearly every affair in Church life in which he took active interest involved large issues or had an almost world-wide Wirkungskreis. It was the same in business; from the first his mind turned naturally to the larger and more remunerative branches of his profession. As some one once put it, he ‘thinks in millions’ and ‘takes large views.’

This trait was exhibited many years ago in a little matter that will be of peculiar interest to his Methodist friends. Prompted by his father’s love of ecclesiastical research, he conceived the idea of mastering all the intricacies of Methodist law and usage from Wesley’s day to his own. As a preliminary step he began to accumulate a great Methodist library, advertising widely for ‘books, manuscripts, documents, or Connexional reports,’ bearing upon the constitution or administration of the Methodist societies.[3] But when he came to investigate, his intensely practical mind drove him to the conclusion that the whole project was a weariness and a waste of

[start of page 227 in original pagination]

time. The chief matters with which the Methodist fathers were concerned, he says, and over which they sometimes quarrelled, like the schoolmen of old, were comparative trifles, having little or no relation to the practical issues of life. To occupy himself with such things seemed therefore too much like using the muck-rake, ecclesiastical minutiae and doctrinal hair-splitting being the filth and garbage, and the application of the gospel to modern needs, the crown of life.

It is almost superfluous to add that Sir Robert is an avowed individualist. ‘I am an individualist all round the compass, so to speak,’ he once said. ‘In commerce, in politics, in the Church — in all these spheres of public life, I have, by training or experience, or what-not, been a very strong individualist, rather opposed to centralization.’ One reason for this opposition is, that centralized authority, on account of its impersonal character, is not readily amenable to moral sanctions, and once established, may survive through many generations, whereas the worst individual tyrant in the world must sooner or later cease to be. He added that his long experience of commercial concerns had taught him that, as a rule,

[start of page 228 in original pagination]

on boards of directors and similar bodies there was a lower standard of morality than was the case with the individual employer.

As some well-known Methodists have declared themselves Socialists, while Sir Robert, as we have seen, belongs to the opposite sociological camp, I may here quote his views on this vexed question. From these it appears that, individualist though he is, he and his brethren are agreed on two essential points: the need for comprehensive social reform, and the duty of the strong to help the weak. Writing two years ago in The Methodist World — a monthly journal with which he was financially associated[4] — on the subject of ‘Methodism and Socialism,’ he said:

‘It should not be forgotten that although John Wesley was an ardent and very original social reformer he was no Socialist. He had read too much history, and was far too practical to accept the wild theories of communistic sociology. Change the life, he urged, and you will change the home. Reform the home, and you will alter the city. Cleanse the city, and you will establish and strengthen the State. All this Wesley declared was primarily the duty of the individual citizen. He combated with all his force the Utopian doctrine of the

[start of page 229 in original pagination]

Anabaptists, that property should be held in common. In pointing out the strongly individualistic teaching of the founder of Methodism, and declaring our belief that many of the theories of modem social reformers, who claim to be Christian teachers, have no basis in Scripture, and can have no place in a well-ordered and progressive State, we must not be assumed to urge that societies, whether religious or municipal, or even industrial, should not be required to utilize their federated strength for the uplifting of the weaker members of the body. It is on this sound platform that the Methodist Church has so successfully and patiently worked. An old country like England has social burdens to bear, and duties to perform, of which younger and more scantily peopled States know nothing. Parliament may have to devise some method for compelling the richer members of the State, not merely among what are called the upper, but also among the prosperous middle and artisan classes, to take their fair share in succouring and providing for the vast army of helpless yet deserving poor, who are living on the verge of destitution. What form this compulsory philanthropy should take we are not prepared at the moment to say. That something on a colossal scale will have to be attempted we are quite sure, and to this task Church and State, working in close and voluntary alliance, should speedily address themselves.’

[start of page 230 in original pagination]

But, to revert to the morality of money- making, it is after all the use of wealth, rather than its accumulation, that is the test of character; for therein the motives of its acquisition stand self-revealed. Reference has already been made to Sir Robert’s generosity, and it is unnecessary to say more, except this, that his gifts have generally been of that thoughtful character which stimulates self-help, that they have been bestowed almost as freely outside his own Church and his own Parliamentary division as within them, and that, disbelieving in the endowment of charity, he prefers to give all he can during his lifetime rather than to bequeath it at his death. A friend of the family, who has intimate knowledge of Sir Robert’s affairs, assures me that the latter’s gifts to charity and politics during the last five-and-thirty years cannot have amounted to less than a hundred and fifty thousand pounds.

Monetary gifts, however, are by no means the supreme form of generosity. Hospitality ranks higher, and in it Sir Robert and Lady Perks have conspicuously shone. Their beautiful home at Kensington Gardens has been freely opened to thousands of people whose sole claim upon them has been their

[start of page 231 in original pagination]

religious and philanthropic associations. Again and again, when a Methodist Conference or a congress of social or religious workers has been held in London, have these generous friends welcomed its members to their residence and bountifully entertained them. At the first Oecumenical Methodist Conference in 1881, for example, they extended their hospitality to the whole sixteen hundred delegates, both white and coloured[5]. There are times when such exposure of the domestic sanctuary, such unveiling of private tastes and family possessions to crowds of strangers, must make heavy demands upon the magnanimity of those who, like Sir Robert and his wife, go little into society and cling tenaciously to domestic joys.

This leads me to speak of one side of Sir Robert’s character that is little understood. It is said of Bulwer Lytton, the novelist, that the airs of indifference and frivolity he some-times assumed were partly the devices of a shy nature to protect itself from unsympathetic notice. Somewhat similarly. Sir Robert’s apparent harshness in debate and his occasionally curt manner with strangers, are partly — I will not say wholly — the devices of a sensitive nature to shield itself against attack. Where

[start of page 232 in original pagination]

a high sensibility exists side by side with conscious power of retaliation, a wound, and sometimes the mere fear of one, will often provoke a retort which, taken alone, would give a totally false impression of him who makes it. That in Sir Robert’s nature there is a real combination of tenderness with strength, I trust this volume has already shown; but the supreme evidence is furnished by his home-life, which has always been singularly sweet and happy. Instead of indulging himself in those selfish gaieties which wealth and position can so readily command, he has devoted himself without reserve to all kinds of philanthropic movements and disinterested advocacies, and at the close of each arduous day has been content to seek, not the playhouse or the clubroom, but the old-fashioned, often despised, but none the less genuine and abiding, pleasures of the domestic hearth.

In all his activities Sir Robert has found a keen sympathizer in Lady Perks, who supplements his labours with many personal ministries of her own. Throughout the Louth Division she is respected by all and beloved by not a few. Though prevented from being by her husband’s side in his first contest[6], she has

[start of page 233 in original pagination]

not failed him since, and as first President of the Louth Women’s Liberal Association[7], and by identifying herself with every local movement for the betterment of the people, she has not only strengthened his hands, but has materially advanced the Liberal cause in the division. Another branch of public service that has won her ladyship’s warm support is work among women and children, and for some years she has made herself personally responsible for a rescue home for the unfortunate members of her sex[8].

But it is in her duties as a housewife that Lady Perks takes chief pleasure, having little sympathy with those women who make ‘home’ but a lodging, while they dissipate their energies in other people’s business. She takes great pride in her charming homes, which are crowded with books, paintings, engravings, and all sorts of delightful curiosities indicative of cultured tastes. As a hostess her ladyship is gracious and tactful, and whether she be entertaining prominent statesmen or humble Methodists from the country, her kindly, almost diffident bearing wins all hearts.

Sir Robert’s union has been blessed with five children, who have taken an active part in

[start of page 234 in original pagination]

various philanthropic enterprises. His eldest daughter was for six years Treasurer of the Young Leaguers’ Union of the National Children’s Home and Orphanage[9]. His third daughter, Edith Mary, was married last December to Fleet-Paymaster Bertram C. Allen, R.N., of the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, at the Bayswater Wesleyan Chapel, the officiating ministers being Dr. D. J. Waller, Ex-President of the Conference and Chairman of the Second London District, and the Rev. George Hammond, the Superintendent of the Bayswater Circuit. After the ceremony, which was the most brilliant in the history of this famous chapel, Sir Robert and Lady Perks held a largely attended reception at Kensington Palace Gardens[10]. Sir Robert’s only son, Mr. Robert Malcolm Mewburn Perks, after completing his studies at the Leys School, Cambridge, is being trained as an engineer and will succeed to his father’s business[11].

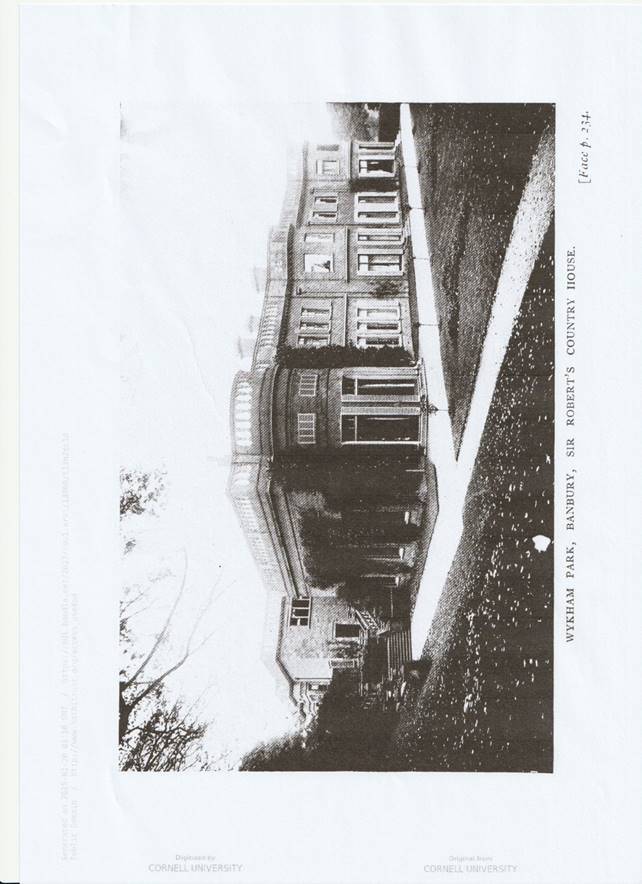

In addition to his town residence Sir Robert has a country house at Wykham Park, Banbury, and a seaside home at Littlestone, Kent. The Wykham Park estate was bequeathed by the late Mr. William Mewburn to his only son, who, on the death of his mother in 1902,

[start of page 235 in original pagination]

sold it to Sir Robert. Since acquiring the property, the latter has made extensive alterations, building a new wing to the house and a picture gallery and library[12]. The stables of the estate are constructed out of what was once a row of ancient houses, in the upper rooms of which some of Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers were quartered after the battle of Edgehill.[13]

The handsome residence at Littlestone was built through Sir Robert’s connexion with the Lydd Railway. In the ample grounds stands a small hall, formerly used for divine service.[14] Although their seaside home is always ready for occupation at a moment’s notice. Sir Robert and his family rarely spend more than a couple of weeks there in the course of the year. Its title, ‘Claverley’ — which was also given to their Chislehurst residence — is derived from one of Sir Robert’s ancestors, whose memory his father cherished with peculiar affection. She was a stiff Jacobite, who whenever prayers were read for the House of Brunswick refused even to kneel. Her father was an officer in the Young Pretender’s army and fought for him at the battle of Culloden.[15]

Sir Robert’s diversions are found chiefly among his books and papers. His library

[start of page 236 in original pagination]

comprises altogether some fourteen thousand volumes, of which nine thousand are accommodated in an exceptionally handsome chamber at his Kensington mansion. This section includes books on politics and general literature, historical and biographical works, and the standard books of reference. At Wykham Park are his volumes on art and archaeology, county histories, and sufficient works of reference to meet occasional need.

Sir Robert has little appetite for light literature. He reads, or attempts to read, perhaps two novels a year, and even then, he says, generally sticks fast in the middle. This is not comforting to the novelist, who doubtless hopes that power to purchase and capacity to consume may always go together. Sir Robert confesses, however, that a year ago he read one novel through from cover to cover at a single sitting. The writer who achieved this conquest was Mr. A. E. W. Mason, M.P., with The Broken Road. Readers who are familiar with the work will not be surprised that Sir Robert’s practical mind should be fascinated by its brilliant pages[16]. His love of serious reading was well illustrated once when he was showing a friend a school prize, the

[start of page 237 in original pagination]

Works of Bishop Hooker, in two volumes. ‘Of course you have not read it?’ said the visitor, handing it back. Promptly came the rebuke — ‘Every line, sir, from the first page to the last’![17]

The same serious vein shows itself in his holidays, many of which are closely interwoven with business projects. Even at Braemar and in Switzerland, two of his favourite resorts[18], he is generally occupied with paper and pen, and he emerges from his retreat with some political pamphlet, or, more frequently, with some vigorous contribution to the Press on the affairs of his Church or the cause of religious liberty. Nor do his religious interests forsake him, as is the case with some, when the object of his travels is purely business.

Some years ago, on his way to St. Petersburg, where his firm were busy in the survey of a railway from Viatka to Vologda, he spent a Sunday in one of the capitals en route. There being no Methodist chapel in the city, he went with his wife and children to the Anglican Church. The congregation was a motley one — English tourists, American globe-trotters, and in the front pews the members of the local British colony. Presently a venerable

[start of page 238 in original pagination]

clergyman, in a white surplice with a crimson hood, mounted the pulpit, and taking from the folds of his gown a well-worn manuscript, commenced his sermon.

‘We had been spending a good deal of the morning in describing ourselves as miserable sinners,’ said Sir Robert, telling the story afterwards. ‘The preacher boldly called us criminals. He described in harrowing language our pitiable state, which he ascribed to heredity. Our parents might have been thieves or drunkards, or, if our fathers and mothers were not, then our remote ancestors were. Then came a few philosophical words about evolution. “Some of you,” said the preacher, “cannot read or write.” We looked at one another and then at the reverend gentleman in the pulpit. Something evidently was wrong. He was nervously fingering his manuscript. His sermon was clearly being delivered to the wrong congregation, for, hastily pulling himself together, he said: “Of course, that does not apply to my present hearers.” A sigh of relief passed through the building. The preacher turned nervously over the well-thumbed leaves, selected cautiously a few more

[start of page 239 in original pagination]

passages, and brought his discourse to a rapid end. The good man was, it appeared, a prison chaplain, and had brought with him on his Continental travels the wrong sermon. As I was going out I heard the wife of the resident clergyman explaining to some friends that the preacher was a stranger. “But,” said the vivacious little lady, “it is such a relief not to hear one’s own husband.” What he might have been we shuddered to think as we thanked God for ministers who could preach without manuscripts.’[19]

When absent in Canada and the States, too, on the great business enterprise already referred to in these pages. Sir Robert’s energies overflowed into non-commercial and non-industrial channels. He visited numerous churches and addressed several important meetings. In New York he spoke to a large gathering of ministers, at which many eminent personages were present; and at Ottawa he delivered a striking speech on ‘British Methodism of To-day: Its Work and Ideals.’[20] Wherever he went he kept open eyes. He did not shrink from criticizing the services he attended and the sermons he heard, and in a series of graphic and invigorating letters home

[start of page 240 in original pagination]

— which letters it puzzled his friends how he found time to write — he told what he had seen and heard.

Clearly, then, the great religious and humanitarian causes with which he has been identified have not been espoused from ulterior motives, but are, so to speak, part of the man himself. His activities therein have been but so many modes of self-expression, and, to trace things back to their source, so many fruits of a wise parent’s love and care. Thus, whatever Sir Robert Perks may have missed of the lighter, more volatile joys of life, he has had his cup filled to the brim with those serener and more lasting pleasures which spring from earnest purposes steadfastly maintained and not infrequently fulfilled. And while a life thus spent in honourable endeavour has brought its indubitable rewards, it may I think be claimed, in concluding my pleasant task, that he has not failed in service to his fellows, and that his career is not without suggestiveness, alike for its independence and its consistency, to those whose record is yet in the making.[21]

Endnotes to Chapter Ten

[1] At the time Crane was finalising this biography, Perks’s office address (according to Who’s Who) was 15 Great George Street, Westminster. This was the head office of C.H. Walker an Co Ltd (see notes 11 and 12 to Chapter Four). The issues of Who’s Who for 1902 to 1908 inclusive had given Perks’s business address as Hamilton House, Victoria Embankment — the location of the head offices of the Metropolitan District Railway and associated companies (see notes 14 and 15 to Chapter Three).

[2] In 1930 Crane (using his own name, Walter Thomas Cranfield) edited a volume titled Journalism as a Career, with the lengthy subtitle: Plain Counsels by Leading Journalists on the Qualifications and Training Needed; The Duties and Conditions of Work and the Monetary and other Rewards that may be expected (London, Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1930). Cranfield wrote the Chapter titled “The Free Lance” (pp. 67-74). There is a photograph of him opposite page 67, with a caption which commences: “Entered Fleet Street in 1905 without a friend. Took a room over the ‘Cheshire Cheese’, bought a typewriter, and began to write — at first for the weekly Press.” There is no mention in this 1930 volume of Cranfield having used the non-de-plume Denis Crane.

[3] Perks appears to have been engaging in this activity during 1877. It is the subject of a short letter signed by him, dated 15 May 1877, held by the Rylands Library at the University of Manchester.

[4] The Methodist World was first published in January 1906. Perks signed the article “Our Aim” which appeared in the first issue. He stated: “The Methodist World will, its promoters frankly admit, be a Democratic Liberal Paper. … while not a political journal [it] will be found, as a rule, to be in sympathy with the policy and the ideals of the Liberal party.” Perks went on to say that: “One of the main purposes of The Methodist World will be to advocate the union of British Methodism.” (The North Wales Weekly News, 26 January 1906, p. 12).

[5] This sentence is a garbled version of a sentence in the unsigned article “Mr. R.W. Perks, M.P.” published in The British Monthly of January 1903 which read: “… he was secretary of the first Oecumenical Congress held in London in 1881, and treasurer of the recent Congress in 1901, when he and Mrs. Perks entertained all the members, numbering sixteen hundred people, including the coloured delegates, at their beautiful mansion in Kensington” (p. 80). That event took place on Tuesday 10 September 1901. The Methodist Times of 12 September 1901 (p. 669) reported that “a spacious marquee, where refreshments were served, had been erected in the garden.” The total number of delegates at the Conference was 400. The figure of 1600 included their wives and various other invited guests.

[6] Crane had referred to this in Chapter Eight. See pp. 181-182 and note 16.

[7] The decision to form a Women’s Liberal Association for the East Lindsey (or Louth) constituency was made at a meeting held in the Louth Liberal Club on 9 November 1892. The same meeting resolved to invite Edith to act as president of the new body (Stamford Mercury, 11 November 1892, p. 5). Edith chaired the first public meeting convened by the new Association, held on 7 April 1893. The guest speaker at this meeting was Perks (ibid, 14 April 1893, p. 3).

[8] The “rescue home” Crane refers to here was named as being “Beacon House” in Perks’s article “My Methodist Life” published in The Wesleyan Methodist Magazine of 1906. Beacon House was established in 1899 (or thereabouts) and located at 261 Vauxhall Bridge-road. It was managed by Margaret Anderson, who was usually referred to as “Sister Margaret”. Prior to the establishment of Beacon House, Sister Margaret had undertaken “rescue work” in conjunction with Mrs. Hugh Price Hughes at the West London Wesleyan Mission.

[9] Perks’s eldest daughter Gertrude was born on 7 September 1879 at “Claverley” in Chislehurst. The Young Leaguers’ Union was established in early 1900, with the Countess of Portsmouth as its president and Gertrude as treasurer. Its primary purpose appears to have been to nurture the formation of a network of branches across the country, through which young people would raise funds to go towards supporting the Children’s Home and Orphanage, founded by Thomas Bowman Stephenson (1839-1912) in 1869. See The Methodist Times, 5 April 1900, p. 224. As well as being treasurer of the Y.L.U. as a whole until stepping-down in 1907, Gertrude was active in the Beckenham Branch of the organisation (The Manchester Courier, 5 June 1907, p. 10; Beckenham Journal, 27 June 1903, p. 6). Gertrude died on 3 February 1914 at 11 Kensington Palace Gardens. She had never married.

[10] Edith Mary Perks was born on 22 February 1884 at “Claverley” in Chislehurst. She married Bertram Cowles Allen (1875-1957) on 18 December 1908. The marriage was reported widely in the press, with the Daily Mirror of 19 December 1908 (p. 11) publishing a photograph of the bride and groom as part of its report.

[11] Crane’s wording here seems to suggest that at the time this biography of Perks was being finalised, the seventeen year-old Malcolm had left The Leys School and had commenced being trained to become an engineer. Malcolm accompanied his father on Perks’s voyages across the North Atlantic in each of the three years 1910 to 1912. When arriving in New York in each of March 1910, September 1911, and April 1912, he reported his occupation as “student”. When Malcolm arrived in New York with his father in March 1914, he reported his occupation as “clerk”. There is no record of Malcolm ever having obtained any formal qualifications as an engineer. But in the 1921 Census he reported his occupation as “Engineer for Public Works Contractor”, and he reported his employer as being his father.

[12] Perks’s father-in-law died on 25 May 1900 at Wykham Park, aged 83 and Edith’s mother died there on 27 January 1902, aged 79. The alterations to the house and grounds organised by Perks after his purchase of the property were truly extensive and took a number of years to complete. Descriptions of the work were reported in The Banbury Guardian 6 September 1906, p. 7; and 2 January 1908, p. 6. Some of the building work was carried out by Messrs Ford and Walton Ltd of London — a company Perks had registered in 1903, with Perks’s nephew Robert Hugh Volckman (1876-1950) as one of its initial directors. In 1913, Perks put Wykham Park up for sale. It was advertised as “A Freehold Estate of 403 acres” (Country Life, 26 July 1913, p. xv). But Perks did not actually sell the property until 1917. In a “Valedictory address” given in Banbury on 22 May 1917, Perks described how in 1902 he: “intended to spend the rest of his life amidst country scenes … trying to master the intricacies of farming life …”, but developments in his business activities had intervened and prevented this from coming to fruition (The Banbury Guardian, 24 May 1917, p. 8).

[13] Perks made reference to this during the course of an address he gave at the Empire Club of Canada on 27 May 1909, saying: “In my home in Oxfordshire, close to where the great Battle of Edgehill was fought, there lived three hundred years ago an old Colonel of Cromwell’s army who was told the night after Edgehill to move his soldiers along quickly and cut off King Charles’s retreat from Banbury to Oxford. Instead of doing so he allowed his men to sleep in what are now my stables.”

[14] Perks’s “seaside home” facing onto the seafront at Littlestone-on-sea was a substantial property. After Perks’s death, it was put up for sale, with the advertisement stating: “Eminently suited for Private Hotel, Hostel, Nursing Home or similar Establishment. Four reception rooms, sixteen bed and dressing rooms, two bath rooms, complete domestic offices and staff rooms … ‘The Hall’, a substantial modern building with assembly room, 50ft by 30ft, Stage and Dressing Room. Garage for six cars. Charmingly laid-out grounds of 4 acres, with Valuable Frontages to three roads” (The Observer, 7 April 1935, p.37 ). An article in The Worcestershire Chronicle of 9 June 1894 (at p. 3) stated: “Littlestone-on-sea competes with Sandwich as a ‘Saturday to Monday’ rendezvous for Metropolitan golf players, and is very largely patronised by Members of Parliament. It has been rapidly developed during late years; mainly through the financial genius of Mr. Perks, M.P., who has a fine house there. Mr Perks is a frequent Sunday visitor to Littlestone; not, however, to play golf.”

[15] The Perks ancestor Crane refers to here was the paternal grandmother of Perks’s father George Thomas Perks. Elizabeth née Claverley (c. 1747-1840) married George Perks at St. Peter’s, Wolverhampton, in January 1780. Elizabeth played a significant role in the upbringing of her grandson G.T. Perks and his three siblings. G.T. Perks’s mother died when he was eight. His father died when he was eleven (see notes 4 and 5 to Chapter One). The parents of Elizabeth Claverley were Thomas Claverley and Mary née Stephenson, who had married at Cheswardine in Shropshire in 1737. I have not seen any evidence linking Thomas Claverley to the army of the Young Pretender. If it is true that he fought at Culloden, he must have survived that experience as Elizabeth appears to have been born about 1747 (baptised May 1750 at Edgmond, Shropshire), — and she has a younger sister Jane who was baptised in 1753.

[16] Alfred Edward Woodley Mason (1865-1948) became the endorsed Liberal party candidate for Coventry in 1903 and won the seat in the general election of 1906. He is probably best known for his novel The Four Feathers published in 1902. The Broken Road was published in 1907.

[17] In 1863 the Oxford University Press published a New Edition of The Works of Richard Hooker, advertised as: “Edited, with Notes by the Rev. John Keble, M.A.” (The Bookseller, 31 October1863, p. 666). This was priced at 31s 6d and came in three volumes. If Crane is correct about Perks’s prize being in two volumes, that was the earlier version, without the Rev. Keble’s notes and additions. That edition was more modestly priced at 11s.

[18] Davos in Switzerland seems to have become a favoured destination for winter holidays by the Perks family. There may have been a health angle involved — to get Edith and her daughters away from the winter smogs in London. In the winter of 1895-96, Perks left London for Davos on Thursday 5 December, together with Edith and ‘the Misses Perks.” He returned to London in early January but Edith and her two eldest daughters stayed-on at Davos until February. The following November the Women’s Liberal Association in Louth was told that Edith’s: “health was so much improved that she hoped to be able to winter in England” (The Stamford Mercury, 27 November 1896, p. 5).

[19] The experience in the Anglican church recounted here took place during August or early September 1899. Perks told the story at a Wesleyan meeting held in Bardney, Lincolnshire on 10 October 1899. Edith was present at that meeting, which probably means that Perks did not over-embellish his account. The report published in The Methodist Times of 19 October 1899 (p. 730) was headed: “Mr. Perks’s Amusing Story” and ended with the sentence “The above story was related in Mr. Perks’s characteristic style, and was, as may be well imagined, highly appreciated by the audience.” Crane’s two paragraphs here are a slightly edited version of the report published in The Methodist Tims, which itself had appeared earlier (word for word) in The Boston Independent and Lincolnshire Advertiser of Saturday 14 October 1899 (p. 5) under the heading “Mr. Perks’s Experience in Russia.”

[20] This appears to be the address Perks gave at the Dominion Methodist Church in Ottawa on the evening of 16 September 1907. See Ottawa Free Press, 17 September 1907, p. 5.

[21] With this, Crane’s biography of Perks ends. There was no index. There were no appendices.