Chapter 4: Men and Matters

A scan of the original unannotated document can be accessed from the HathiTrust Digital Library collection at

The Life-Story of Sir Robert W. Perks, Baronet, by Denis Crane.

[start of page 71 in original pagination]

Chapter IV: Men and Matters

In the course of his long and active business career Sir Robert has enjoyed the confidence and friendship of many distinguished men, but none stands out more conspicuously in this respect than Sir Edward Watkin, the famous railway potentate[1], and Mr. Thomas Andrew Walker, an equally talented railway contractor.[2] With both he had for many years the closest relations, and to them he owes more, from a business point of view, than to any two other men.

I have spoken of his friendly associations with Lord Penrhyn. These brought him into contact with another well-known Conservative peer. Lord Cranbrook. In the summer following his wedding it fell to Sir Robert’s lot to introduce to the South-Eastern

[start of page 72 in original pagination]

Railway Board a deputation of the Cranbrook Railway to protest against the action of Sir Edward Watkin’s company.[3] His language on the occasion is said to have been more forcible than convincing, but at least it had one good effect — it made a favourable impression upon the famous railway magnate. Six months elapsed, however, before Sir Robert’s chance came.

On the following Christmas Day he was sitting at dinner at Wykham Park, when a telegram was put into his hand. ‘Sir Edward Watkin arrives in London to-night from Manchester, and wishes to see Mr. Perks at Cleveland Row on important business.’ Sir Robert handed the message to his wife. It was their first Christmas together after their marriage, so who can blame her that she suggested postponement ? Her father supported her. ‘Wire saying you will be there to-morrow,’ said he.

But Sir Robert saw that his opportunity had arrived, and at six o’clock that same evening he was waiting in the railway magnate’s library. ‘I wondered if you would come,’ was the latter’s only comment, as he pulled off his heavy fur coat. From that day

[start of page 73 in original pagination]

forward for fourteen years Sir Robert was by Sir Edward Watkin’s side in all his battles.[4] Business simply poured into his lap. For all the railways over which Sir Edward held control, and they were not a few, he was employed, and it is interesting to know that on one occasion only did he seriously differ from his chief on a question of railway policy. This was concerning the costly extension to London of the Great Central Railway, then the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire line.

The course advocated by Sir Robert was to extend the Metropolitan Railway northward to meet the Sheffield line, then coming south from Nottingham and Leicester to Rugby. This plan would have given the latter company running powers over the Metropolitan line to Baker Street Station, which, after enlargement, would have served as a terminus for both. Instead of this conservative and manageable scheme, the extension to London was undertaken, at a cost of many millions. It is whispered that personal ambitions and antipathies had more to do with the adoption of this course than considerations of expediency or finance.[5]

[start of page 74 in original pagination]

The acquaintance of Mr. T. A. Walker was made in the spring of 1880. Sir Robert was standing one afternoon on Appledore railway platform with Sir Edward Watkin, when the latter, pointing straight across the Romney Marshes to Lydd Church, whose square tower was visible in the distance, exclaimed: ‘Perks, we ought to have a railway right across there. The land is perfectly flat, and the cost would not be great. I should like to find some one to build such a line. I would work it for the South-Eastern Company and guarantee the stock.’

At once the idea flashed into Sir Robert’s mind, Why should not he build the road? And turning to Sir Edward he said: ‘If you will allow me, sir, I will build it.’ Sir Edward was considerably startled, but he took his friend at his word and allowed him and his relatives, whose aid was enlisted, to execute the project[6]. Neither party had reason to regret the result.

But the question arose. Who should be employed to construct the line? Sir Edward Watkin advised the appointment of Mr. Walker, who at that time was busy building the Dover and Deal Railway, and the counsel

[start of page 75 in original pagination]

proved in every way wise. This was Sir Robert’s first attempt at practical engineering, and it formed the commencement of an intimate friendship with Mr. Walker which lasted till the latter’s death. The well-known contractor was a Christian gentleman in the highest sense, and a scholar of no mean order. Quiet and resourceful, he inspired to an unusual degree confidence in his ability to deal with difficult problems.

Sir Edward Watkin professed to be a great admirer of the Methodists, but he had not a very rigid belief in the sanctity of Sunday. ‘Shortly after I was made the lawyer of the Metropolitan Railway,’ said Sir Robert at a Sunday Observance meeting a few years ago, ‘Sir Edward Watkin came down to Blackpool one Saturday afternoon with his wife, and, coming into the lodgings where I was staying, said he wanted me the next day to go through all the papers for a railway Bill, and get the briefs ready for counsel. I told him I never did legal work on Sunday. ‘Then what,’ said he, ‘is the use of such a lawyer ?’ I replied that if he would hand all the papers to me the work should be done by midnight, and on Monday morning I

[start of page 76 in original pagination]

would get up early and have all ready. This was done, and I was never asked again by the Chairman to work on Sunday.’[7]

The friendship was fruitful in connecting Sir Robert with a number of public works of considerable magnitude, both at home and abroad. The first of these was the Barry Docks and Railways in South Wales, in dealing in the ‘ paper ‘ of which he is said to have ‘made a little fortune.’[8] The great change wrought in the locality by these undertakings, which have given employment to tens of thousands of people, will appear from the fact that prior to their commencement the site now occupied by the great coal docks and the important town of Barry was mainly green fields ; with the exception of an old farm-house or two, a country residence in the valley, and a quiet church, not a building was to be seen. The docks now ship hundreds of thousands of tons of coal every year, and the town is one of the most prosperous and progressive in South Wales.

The Preston Docks and the Manchester Ship Canal were other big concerns with which Sir Robert and his friend were con-

[start of page 77 in original pagination]

nected. The contract for the latter was let for a sum of £5,600,000. At the time of Mr. Walker’s decease, in 1888, some two millions of this amount had been spent. During the following year nearly two million pounds’ worth of additional work was done. Mr. Walker’s executors subsequently came to an arrangement with the Canal contractor to retire from the work, which they were glad to do, it is said, with a very insignificant profit.[9]

Their largest and most successful under-taking, however, was the great Harbour works at Buenos Ayres, for the Argentine Government. These were started in 1887 and completed only five years ago.[10] They involved the turning of the mud banks of the River Plate, for a distance of three miles in front of the city, into a magnificent series of docks, locks, and quays, with numerous gigantic warehouses and railway sidings, and up-to-date equipment ; and the dredging of two deep channels from the dockside out to sea for a distance of seven or eight miles. Mr. Walker’s death so soon after the commencement of the work threw the responsibility for its completion upon the shoulders of

[start of page 78 in original pagination]

Sir Robert and his present partner, Mr. C. H. Walker, who now constitute the firm of Messrs. Walker and Co.[11] It is gratifying to think that these vast works, costing nearly eight millions sterling, fell to a British firm. They reflect equal credit upon that progressive and prosperous young nation, the Argentines, and upon the courage and enterprise of English contractors ; for the undertaking is perhaps the largest ever essayed abroad by a British firm.

Messrs. Walker & Co. are evidently bent upon maintaining their reputation for handling with success gigantic schemes, for they are now constructing a magnificent quay wall, several miles long, round Rio Bay, for the Brazilian Government — a work of great difficulty and magnitude. They are also piercing the Andes between Argentina and Chile, so that soon these two neighbouring Republics will be connected by railway, and passengers will be able to travel through from Buenos Ayres to Valparaiso without change of car.

Incidentally it may be stated that Sir Robert and his partner, in connexion with their South American business, own extensive

[start of page 79 in original pagination]

estancias in Uruguay, with many thousands of cattle and sheep. They are also the owners of large granite quarries in Uruguay and Brazil, with railways, piers, and numerous steamers.[12]

In this connexion, too, it may be mentioned that in recognition of his many services in the engineering world. Sir Robert was many years ago elected an Associate Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers. This is a distinction which has fallen to few men outside the profession. His proposers were Sir John Hawkshaw, Sir John Fowler, and Sir James Brunlees.[13]

Among the other notable personalities with whom his many interests brought him into contact, was the late Comte de Paris, the eldest son of King Louis Philippe. The first business of importance which Sir Edward Watkin entrusted to him, after that memorable summons from the Christmas dinner-table, was an expedition to France, to prepare a confidential report on the Northern of France Railway, and on the possible accommodation at the little seaside town of Treport for a Channel steam service. He was also instructed to continue negotiations then in

[start of page 80 in original pagination]

progress between Sir Edward and the Orleans Prince for the purchase of the latter’s interest in the Treport railway. The acquisition of that interest would have given to the South-Eastern Railway an important length of line running direct to Paris.[14] On several occasions Sir Robert saw the Comte de Paris. On one of them the latter gave him a highly graphic account of the landing at Treport of a large flock of English sheep. Sir Edward’s venture unfortunately proved abortive, partly through the enterprise of the Northern of France Railway, but mainly owing to the internal feuds then raging among members of the South-Eastern Board.

The Channel Tunnel scheme will long rank as one of the most fascinating projects in the history of British enterprise. Sir Robert was entrusted with the difficult, indeed the almost impossible, task of passing the original Channel Company Bill through Parliament. He fought for the scheme against the Crown, and also took charge of it when it came before a joint committee of the two Houses, on which occasion it was rejected by a majority of one only, viz. five votes to four. The chairman of this committee, who prepared a

[start of page 81 in original pagination]

masterly and voluminous report upon the Tunnel project in its commercial, political, engineering and military aspects, defending and advocating it on all grounds, was none other than the leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Lords and the late Foreign Secretary, Lord Lansdowne. [15]

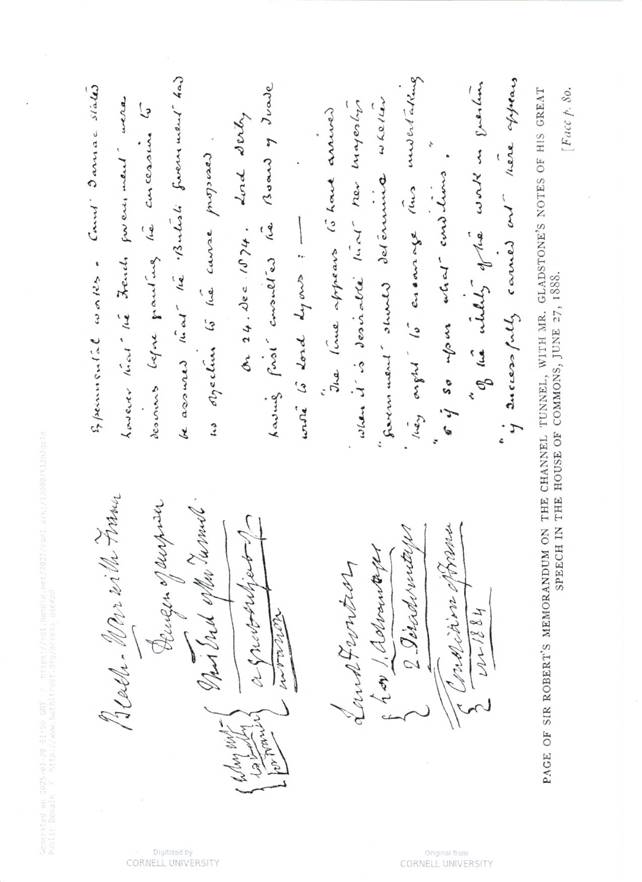

This, of course, was more than thirty years ago, when the project had the support of many leading statesmen. John Bright, for example, was a warm friend. Mr. Gladstone, too, with whom also Sir Robert came into frequent contact, was a convinced and enthusiastic believer in the commercial and political advantages of direct railway communication between England and the Continent. He attached little importance to the alleged military dangers. Indeed, on more than one occasion he declared that a time might come when the existence of such a connexion might be a source of ‘military strength to this country. Sir Robert still retains a lengthy manuscript which he prepared for Mr. Gladstone, and which is covered with the notes used by the famous statesman in his defence of the project in the House of Commons.

Another distinguished personage whom Sir

[start of page 82 in original pagination]

Robert met at this time was M. Leon Say, who naturally looked at the scheme from the French standpoint, and moreover from that of an economist of the Cobden school. He had the pleasure on one occasion of travelling with the distinguished Frenchman to the head of the Tunnel, more than a mile beneath the Channel, to show him Colonel Beaumont’s shield steadily cutting out the grey chalk; a work which Mr. Chamberlain and the Board of Trade stopped.[16] The one topic of interest with Monsieur Say was the political and social value of the Tunnel. Commercially, he apparently thought it would benefit France but little — rather the reverse.

Lord Randolph Churchill occupied a some-what equivocal position in regard to the project. True, he was a shareholder in the company formed by Lord Stalbridge, then Lord Richard Grosvenor, for building the Tunnel[17]; but he readily took strong likes and dislikes. ‘I hate Watkin,’ he once exclaimed to Sir Robert; and that was at one time the only reason he assigned for opposing the scheme. In one of the debates in the House Sir Edward, in a weak moment, suggested that the Tunnel might be exploded at any time by an electric

[start of page 83 in original pagination]

button, placed upon the Cabinet’s table in Downing Street. This was too much for Lord Randolph, who had recently left the Ministry. He passed in cynical review one after another his late colleagues, asking if this one or that would ever dare to ‘touch the button.’[18]

A more friendly personage was M. Ferdinand de Lesseps, who, in particular, made light of the engineering difficulties. Indeed, no competent engineer from first to last really hesitated on this point, the stratum beneath the Channel being one continuous belt of grey chalk, which can be cut through like cheese. One day when they were discussing this aspect of the question Sir Robert unwittingly annoyed his chief. Sir Edward had been saying that Providence had laid that stratum there for the express purpose of giving easy access to France, whereupon Sir Robert, with characteristic incisiveness, reminded him that Providence had also placed there a turbulent and treacherous sea.

During the progress of the fight M. Lesseps came over to London. He knew what some of the classes thought: he was anxious to ascertain the view of the masses. To gratify him, a number of working men, carefully

[start of page 84 in original pagination]

selected, were invited to meet him at the Charing Cross Hotel. As the distinguished Frenchman was led up the room by Sir Edward, they were astonished to hear the British work-men shout out in continuous and rhythmical strains, ‘Vive la France — Vive le tunnel sous la Manche — Vive le tunnel — Vive la France!’ It subsequently transpired that an active official of the company had spent several hours teaching the men thus to express their views. Naturally Monsieur Lesseps went back to France with a passionate belief in the intelligence of the British working man and in his desire to avoid the Channel passage.

Here again, it has been stated, personal jealousy and rival interests did more to wreck the scheme than any question of national danger. One of London’s greatest financiers once declared that his firm had never made a serious blunder except where they had allowed their commercial instincts to be warped by personal prejudices. It would be interesting to extend this remark to all the public works of the United Kingdom, and to inquire how many important undertakings have been made or marred by the private ambitions of rival magnates.

[start of page 85 in original pagination]

When a more recent attempt was made to pass a Channel Tunnel Bill Sir Robert assumed a somewhat different attitude. He supported the Government in its discouragement of the project. The necessity for the work, he contended, was not so great now as it was thirty years ago, owing to the shortening of the sea passage, the enormous development of cross- Channel traffic, and the great diversion of trade via Liverpool to Continental ports. Moreover, popular sentiment was strongly against the enterprise, a fact that might involve the country in military expenditure which the commercial advantages could hardly justify. This scheme was to cost sixteen millions. The earlier one, engineered by Sir Edward Watkin, involved a cost of only seven millions, and this sum Sir Robert succeeded in getting guaranteed in London and New York, without underwriting, in forty-eight hours.[19]

Latterly Sir Robert has had large business interests in Canada, where he is represented by his nephew, Mr. George Volckman, at Ottawa. Another nephew, Mr. J. D. Volckman, of Chatham, New Brunswick, represents him on the New Brunswick Pulp and Paper

[start of page 86 in original pagination]

Mills, at Millerton, on the Miramichi River, which are owned by Sir Robert.[20]

He is now taking an active part in a scheme for the construction of a great ship canal in the Dominion, to which scheme Sir Wilfrid Laurier has pledged his Government. It will cost at least twenty million pounds, and will connect the big Canadian lakes with the St. Lawrence by a deep waterway, utilizing for this purpose the French, Mattawa, and Ottawa Rivers. When this canal is cut vessels drawing twenty feet will be able to steam all the way from Liverpool to Chicago, or to Fort William and Port Arthur, and the produce of the North-western regions will reach English or Continental ports without breaking bulk. Should Sir Robert succeed, the canal will rank, as an engineering feat, with the Suez and Panama Canals, while for the boldness of its conception, the vastness of its processes, and the far-reaching nature of its results, it will be one of the wonders of the world. What it may mean to the working classes of this country, in the way of cheaper fruit and bread, is an interesting topic into which there is no need to digress.

In 1907, in connexion with this big project.

[start of page 87 in original pagination]

Sir Robert paid two visits to Canada and the States, travelling over the route of the proposed canal from end to end.[21] On his first visit he had an interesting interview with President Roosevelt. They discussed together various political questions, the social work of the Methodist Church, the possibilities of religious equality in England, railway matters, and industrial combines. Sir Robert was greatly impressed with the President, whom he described in one of his letters as ‘the strongest personality at the White House since the days of Abraham Lincoln.’

A more exciting experience, which occurred on his second visit, was a narrow escape from a forest fire.[22] He had occasion to go from North Bay, a small town on the shores of Lake Nipissing, to Trout Lake, a distance of seven or eight miles; and he set out, accompanied by a friend, a Canadian-French engineer, in a Canadian buggy drawn by a fine pair of horses.

‘We had driven, he wrote, ‘some three or four miles along the country mountain track, when I noticed a cloud ahead.

‘ “What is that dark cloud?” said I.

‘ “Only some homesteaders making a clearing,” answered my friend.

[start of page 88 in original pagination]

‘As we got nearer, the clouds were denser. The air was hot. We heard the bracken crackling, and here and there saw flames suddenly shoot up.

‘ “Don’t be concerned,’ said the driver; “I’ll pull you through all right”—for by this time we were enveloped in smoke.

‘My friend kept his word, for in half an hour we were through the zone of fire with no more discomfort than sore eyes and somewhat stifled lungs. We little thought what was in store for us on the homeward journey. On we drove some miles, and in a few hours turned homewards.

‘Far ahead we could see the dense masses of smoke, blackening the sky for miles. Driving a mile farther we met three or four youths running to escape the bush fire, which was quickly spreading. They told us we could not get through. Our French engineer assured us he could get the horses through, if we would only trust him, and away we shot, the horses snorting and palpitating with fear. All around us the forest trees were in flames. The heat was like a blast furnace. Had the wind driven the flames across the road nothing could have saved us. Providentially it was blowing the

[start of page 89 in original pagination]

other way. I noticed on our right a tall pine; the fire had burned all round the roots. The tree was swaying, now to the right, now to the left. If it fell to the left it would block our road, or fall on us. In either case we could not have escaped. I watched the great tall burning mass sway gently to the right, lean for a moment against the telegraph wires, and then crash down wires, posts, and all.

‘We came to a wood trestle-bridge. The ends of the beams were all on fire. I felt certain that our car when it reached the centre of the bridge would carry the whole structure right down into the stream. The horses, terrified out of their lives, bolted, almost leapt forward — we were across the bridge, and in ten minutes were through the fire, with singed hair and blistered faces to remind us how near we had been to death.’

Sir Robert’s long experience of London railways and of the many problems connected therewith, gives some weight to his views on London traffic in general. This was recognized by the Royal Commission on this complicated question, which sat in 1905-6, and before which he was called to give evidence.[23] Among other recommendations made by him

[start of page 90 in original pagination]

at the time was the appointment of a Traffic Board, to deliberate on such matters as the improvement of the main roads and the effect on the rates of the depreciation of property caused by the unregulated condition of heavy traffic.

In regard to the latter, he pointed out that the vacation of property on the affected thoroughfares, or the appreciable reduction of its value, substantially reduced the municipal exchequer; while at the same time the cost of maintaining the roads was, owing to the heavier wear and tear, perceptibly increased. A considerable share of the taxation for road repairs ought therefore to fall upon the traffic using the roads. Furthermore, particular classes of vehicles ought to be restricted during certain hours to specified thoroughfares. By this means would be abolished that extraordinary civic anachronism, the holding up of important traffic in the middle of the day by a snail-paced van.

On the question of main roads he also enlarged. The tendency at present is for these to lose themselves directly they reach the suburbs. Sir Robert would have them judiciously extended and increased in number, and

[start of page 91 in original pagination]

finally coupled up by a great boulevard encircling the whole city.

A further problem arising out of the rapid growth of the London suburbs is that of cheap fares. As this is a matter upon which in certain quarters Sir Robert has been greatly misrepresented, it may be well here to define his position. The crux of his alleged offence is that, presumably in the interests of dividend-hunters, he has advocated the raising of workmen’s fares. In an interview in one of the morning papers some time ago, he exposed a fallacy upon which, in part, this accusation rests. ‘The English railways,’ he said, ‘do not, as is commonly supposed, belong to a few wealthy capitalists. The stock is held by a multitude of small investors, whose average holding does not exceed a thousand pounds; while very large quantities of stock are also held by insurance companies and friendly societies, who have invested in this way the savings of the working and the middle classes.’[24]

It was reasonable, therefore, he continued, that railways should be run at paying rates. He cited the case of the District Railway, which, since its inauguration, had carried more people than the whole population of the world,

[start of page 92 in original pagination]

and yet, with the exception of one year, had never paid the Ordinary shareholders a half-penny dividend.[25] It was, in fact, carrying seventeen millions of working men each year at a loss. This was bad for the employés of the company, themselves working men; and it was bad for the investors, many of whom (friendly societies and the like) represented the most thrifty section of the same class. Any unreasonable reduction of fares, therefore, was in such cases just putting money in the workman’s right-hand pocket by taking it out of the left ; or even worse, penalizing the thrifty for the sake of those whose financial habits were unknown.

Yet it is not so much the raising of fares that Sir Robert advocates, as their readjustment. In New York there is a twopenny-halfpenny rate for everybody; all are treated alike. The city clerk, who, though he is better dressed, is not always better off, is not made to pay for the working man’s ride ; and the shop-boy who goes to work after eight does not have to pay three or four times the fare his workman father pays. It is a scale of fares without these arbitrary and unreal distinctions that Sir Robert desires to see established.

[start of page 93 in original pagination]

So far, indeed, from being indifferent to the welfare of the working classes, either in this or in any other matter. Sir Robert has in many ways laboured to promote it. In railwaymen, in particular, at home and abroad, he has always interested himself. When he succeeded to the Chairmanship of the Metropolitan District Railway, unlike some other railway directors he invariably adopted a conciliatory attitude towards the men’s association. Mr. Richard Bell met the Board on several occasions, and existing difficulties, some of them rather serious ones, were amicably adjusted without friction by a little giving and taking on both sides.[26]

Interviewed by The Sheffield Independent on the railway dispute of 1907, Sir Robert said: ‘During the last twenty years it has been my lot to be associated with some of the largest public works in the world, and my partners and I had in our employment many thousands of men. I am to-day closely connected with some big enterprises. I have never refused to meet the representatives of the union, and have almost always found that the disputes were capable of solution. I look upon a strike or a lock-out as an economic barbarism, which

[start of page 94 in original pagination]

hardly ever does either employer or employed any good. Huge losses are incurred on both sides far exceeding any pecuniary sacrifices which a settlement might entail. When I landed in New York, the wharfingers were on strike. Italians were imported, and the standard rate of pay fell. When I returned to New York the hotel porters were on strike. In Canada, the telegraph operators struck. I do not think any one gained anything. Mr. Bell, as I understand his contention, does not seek to interfere with the management of the lines, and if he is prepared to limit his representations to the conditions of employment, I can see no reason why the directors should refuse to meet him. Unfortunately, most of the directors of English railways are men who have not personally had a commercial or business training. They are as a rule opposed to trade-unions. If they knew more of the rough-and-tumble of life, they would perhaps not assume such an inexorable position.’[27]

On more than one occasion Sir Robert has at his own expense entertained large bodies of workmen. At the Austrian Exhibition a few years ago, for example, he entertained

[start of page 95 in original pagination]

upwards of three hundred Austrian and Hungarian railwaymen at Earl’s Court. He has also shown great generosity to those whose misfortunes or misdeeds have brought them to distress. The following incident was related to me by one intimately acquainted with the case. A young man got into disgrace through drink. Sir Robert heard about it and determined to give him a chance to regain his self-respect. At some personal sacrifice he found him a position, but imposed the condition that he should become an abstainer. The young man kept the pledge for a time and then broke down. Sir Robert, however, gave him another trial. He broke down again, and yet a third chance was given him. Happily, this time Sir Robert’s forbearance was rewarded, and to-day the man in question occupies a position of honour and responsibility in which his influence is wholly for good.

End Notes to Chapter Four

[1] For an account of Watkin’s life and work, see David Hodgkins, The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin, 1819-1901, Merton Priory Press, 2002.

[2] See Peter Cross-Rudkin`s entry on T.A. Walker in Volume Two of the Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers, and also Richard Clammer, T.A. & C.H. Walker: Shipbuilders, Railway and Civil Engineering Contractors, Lightmoor Press, 2023.

[3] It was on 18 July 1878 that R.W. Perks accompanied the deputation from the Cranbrook and Paddock Wood Railway Company (C&PWR) to meet the board of the South Eastern Railway (SER). The C&PWR deputation was led by John Stewart Gathorne-Hardy (1839-1911), who succeeded his father to become the second Earl of Cranbrook in 1906. Perks served as legal and financial adviser to the C&PWR from the spring of 1878 to 1888 or early 1889. See Owen E. Covick, “R.W. Perks, Sir Edward Watkin, and the Cranbook Railway (a.k.a. ‘The Hawkhurst Branch”), November 2024.

[4] I find Crane’s account here of the events of Christmas Day 1878 bizarre. The reader has already been told (at page 68) that Perks’s connection with Watkin was of paramount importance in the unfolding of his business career. And here we have what Crane has to say about how that connection came into being. The structure of Crane’s account invites the reader to assume that there had been no communication between Watkin and Perks, either direct or indirect, since their first encounter with one another some six months earlier. The telegram from Watkin is presented as a bolt from the blue. Perks’s father-in-law is presented as simply “being there” and volunteering appropriate paternal consideration for is daughter’s feelings, but not otherwise involved. And when Perks races to London to meet Watkin, what happens? Watkin makes one comment to him and one comment only, and that is it! — except that Watkin proceeds to shower Perks with largesse, in the form of lucrative business opportunities. Crane’s Christmas tale bears a resemblance to his story of Perks’s 1877 holiday hotel stay in Llandalino being disturbed by the unexpected arrival of the party of four (see Chapter Three, p. 66). As is that case, the unexpected surprise is followed by swift decisive action on the part of Crane’s protagonist, and happy consequences all round. Crane is particularly economical in the supply of “detail” regarding this momentous episode in Perks’s career. This is in strange contrast to the detail he provides regarding the diet of the Kingswood pupils (pp. 32-33), or Perks’s “ingenious device” for waking himself up in the mornings (p.57). It was not until I read Charles Lee’s entry on Perks published in volume four of the Dictionary of Business Biography that I had any clue as to what Watkin’s Christmas Day telegram was actually about. I have attempted to explain the background to the telegram (and the nature of the services Watkin so pressingly wanted to engage Perks to provide) in: Owen E. Covick, “Watkin’s Struggle at the S.E.R. Board 1876-79, and R.W. Perks.”

[5] The “personal ambitions and antipathies” Crane alludes to here are probably those of the general managers of the two companies: William Pollitt (1842-1908); and John Bell (1841-1911). See David Hodgkins, op. cit., p. 610.

[6] For more on the Appledore to Lydd railway and the financial arrangements put in place for its construction see pages 10-12 of Owen E. Covick, “Mapping the career of a businessman who was an ‘independent operator’ and who left no substantial papers: the case of Sir R.W. Perks 1849-1934”, Paper presented to the 2005 Conference of the Association of Business Historians, Glasgow, May 2005.

[7] This incident probably occurred during the summer of 1882. Sir Edward Watkin and his wife were reported as having spent the Whitsuntide weekend in Blackpool that year, with Watkin making preparations for “the introduction into Parliament of a bill for the extension of the Cheshire lines from Wigan to Blackpool” (The Blackpool Herald, 2 June 1882, p. 8). The London Gazette notice for the Blackpool Railway Bill for the 1883 session of Parliament cited R.W. Perks as being “solicitor for the Bill” (op. cit., 21 November 1882, pp. 5262-5264).

[8] Crane’s preceding interposed paragraph on the issue of the sanctity of Sunday may create a confusion for readers regarding this paragraph. Here, Crane is back to telling us about Perks’s friendship with T.A. Walker. Perks’s involvement in the affairs of the Barry Dock and Railways Company appears to have commenced around April 1887. From 17 June 1887 until July 1890 Perks was a director of that company. This was Perks’s first appointment as a director of a substantial enterprise with a broad base of shareholders. But Crane does not tell us this. For an account of Perks’s activities relating to the Barry company see Owen E. Covick, R.W. Perks and the Barry Railway Company, published in four parts in the Journal of the Railway and Canal Historical Society from July 2008 to July 2009.

[9] Crane is mistaken about the year of T.A. Walker’s death — it was 1889. And according to the Manchester Ship Canal Company’s 1887 prospectus, Walker’s contract to construct the canal was for £5,750,000. Perks was legal and financial advisor to the executors of the T.A. Walker Estate. He organised for a series of private Acts of Parliament to be obtained to allow the executors to continue to operate the very substantial business enterprise which Walker had succeeded in building up. On 27 February 1892, Perks had a “letter to the editor” published in The Manchester Guardian (at p.9), in which he set out some facts and figures regarding the work on the Ship Canal project. Included in that letter was: “Mr. Walker died on November 25, 1889, two years after the canal works had been started. The total amount of work then done was £1,914,864. The executors carried on the works for eleven months, from 25 November 1889 to 31 October 1890. The amount of work done during that period was £1,558,077. …The executors’ arrangement terminated on 25th November 1890.”

[10] Crane seems to be telling us here that the Buenos Ayres Harbour works project he goes on to describe was completed only in 1904 or thereabouts. But The Times of 25 June 1897 had announced the completion and opening of those port works. And on 17 July 1897 (at p. 18) that same newspaper published a “letter to the editor” from R.W. Perks, in which he sought to follow-up on that report: “As these great works have been constructed by English contractors and engineers, and are the largest, the newest, and the best-equipped docks in the American continent, I may perhaps be allowed very shortly to supplement the information contained in your paper.” Perks`s letter refers to the works as having cost “upwards of 7,000,000 pounds.” Crane cites essentially the same figure at the start of page 78. Between 1898 and 1901 C.H. Walker and Co Ltd (see note 11 below) did some additional work for the Argentine Government on the construction of warehouses at the port and dredging the north channel, but even if Crane is including that work in his summary here, the completion date he gives appears to be well out.

[11] The third of the private Acts of Parliament organised by Perks for the T.A. Walker Estate authorised the executors to transfer the business operations of the estate into a limited liability company which would then be able to enter into contracts for work unrelated to the projects in progress at the time of Walker’s death. The company “C.H. Walker and Co Limited” was registered in April 1898 by Perks for that purpose. Charles Hay Walker (1860-1942) and Perks were its principal shareholders. Perks was an initial director of the company and continued to hold that directorship until 1912.

[12] For more on the activities of the C.H. Walker company see the entry on Charles Hay Walker (written by Owen Covick) published in Volume 3 of the Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers, London, 2014. The estancia at Conchillas in Uruguay was the family home of Charles Hay Walker for many years. Perks himself never set foot in South America, though his younger brother George Dodds Perks went out to Buenos Aires in June 1891 for a stay of three months or so. George and his wife later visited Chile for three months, but that was not until 1935.

[13] Perks was elected an Associate Member of the Institution (sic) of Civil Engineers on 5 March 1878, his nomination having been lodged on 22 January 1878. The documentation regarding his nomination and election is available on the Ancestry website. There was one proposer of Perks’s nomination and there were eight seconders. James Brunlees (1816-1892) was the proposer. Neither Hawkshaw nor Fowler were among the seconders. One of the seconders was Thomas Hawksley, whose name Crane may have misheard or misread. The date of Perks’s AICE nomination sits uneasily against Crane’s comment of this being “in recognition of his many services in the engineering world”. On page 73 Crane had told us that the Appledore-Lydd project was “Sir Robert’s first attempt at practical engineering.” Apart from the reference to Perks’s work on the Conway Bridge Bill, Crane’s biography is silent regarding any “services in the engineering world” performed by Perks prior to March 1878.

[14] This passage resembles a segment of the unsigned article “Mr R.W. Perks M.P.” in The British Monthly of January 1903: “The first important work he had to do for Sir Edward was to go over to France to report confidentially upon the extensions of the Northern of France Railway, the capabilities of Tréport Harbour, and the possibility of securing the control of the Abbeville and Treport railways. In carrying this out Mr. Perks made the acquaintance of the late Comte de Paris, with whom he stayed at the Cháteau d’Eu. The intention, which was frustrated by dissensions on the South-Eastern Railway board, was to have used Tréport, which is forty miles nearer Paris than Boulogne, as a competing port to Dieppe” (op. cit., p. 82). Perks’s first visit to France in connection with the Tréport scheme appears to have been in September, or perhaps early October, 1879. A report he had prepared on the scheme was discussed at the 2 September 1880 meeting of the SER board. On 24 September 1881 he wrote to Watkin giving an account of a long meeting he had had with the Comte de Paris the preceding evening. For more on Watkin’s Tréport scheme see David Hodgkins, op. cit., pp. 441-3 and 506-7.

[15] The joint committee of the two Houses that Crane refers to here is clearly the Joint Select Committee chaired by Lord Lansdowne that first met on 20 April 1883, heard evidence through to mid-June, and convened to determine its Report on 10 July 1883. But Crane appears to have been in error in his reference to a vote of five against four. The committee was comprised of ten members, five from the House of Lords and five from the House of Commons. All ten were present at the final meeting on 10 July 1883. Six separate draft reports were put before the Committee. The first to be considered was Lord Lansdowne’s, which as Crane states, was strongly in favour of the Channel Tunnel. It was rejected by six votes to four. The other five draft reports were all against sanctioning the scheme, but for different and in some cases conflicting reasons. None of those five could obtain majority support. The Committee therefore resolved to report that four of its members were in favour of the Channel Tunnel and six were opposed to it. (See the various newspaper reports published on 11 July 1883; e.g. The Standard, p. 5).

[16] Leon Say was among the group which inspected the “preliminary boring operations” on 23 April 1881. The Board of Trade took legal action to stop these “experimental works” in July 1882, arguing that they were in violation of the Crown’s foreshore rights because they involved unauthorised digging below the zone between the high water line and the three-mile limit.

[17] Crane would probably have helped his readers here if he had mentioned that there were at this time two separate and rival British companies seeking authorisation to build the British section of the proposed Channel Tunnel. The Lord Grosvenor company was the 1872-registered “Channel Tunnel Company Limited” which had links with the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LC&DR), chaired by J.S. Forbes. Watkin’s company was “The Submarine Continental Railway Company Limited”, registered by Perks in December 1881. In July 1886 the Watkin company bought-out the rival company in a scrip-for-scrip takeover. And in February 1887 the Watkin company was renamed the “Channel Tunnel Company Limited.”

[18] The debate Crane refers to here took place on 27 June 1888 (on the Second Reading of the Channel Tunnel (Experimental Works) Bill).

[19] This paragraph is couched in much the same language as the unsigned “Special London Letter” published in The Sheffield Daily Independent, 22 March 1907, p. 4.

[20] George William Volckman (1873-1931) and John Douglas Volckman (1874-1953) were two of Perks’s six nephews referred to by Crane at page 69 above (see note 26 to Chapter Three). Perks’s interests in the pulp and paper industry in Canada were a relatively recent development at the time Crane was writing. The Pulp and Paper Magazine of Canada, Vol. 6, No. 11, November 1908 reported (at pp. 286-7). “The new pulp mill promoted by James Beveridge at Millerton, on the Miramichi, a few miles above Newcastle, N.B., is nearing completion and will probably be in operation before the end of the year. Mr Beveridge who has pushed this enterprise with great energy, has obtained a provincial charter for the business under the name of the New Brunswick Pulp and Paper Co. The capital is $200,000 and the names of the incorporators are: Geo. W. Volckman, James Beveridge, John D. Volckman, F.M. Beveridge and A.H. Hannington. We understand that the capacity of the mill will be 50 tons of paper per week, and that Kraft brown papers will be the chief product of the mill.” The January 1909 issue of the same publication reported (Vol. 7, No. 1, p. 28): “The New Brunswick Pulp and Paper Co.’s mill at Millerton N.B. is now complete and the machinery is in place. The president is James Beveridge and the secretary-treasurer is J. Douglas Volckman who was for eleven years with the Ely Paper Mills at Cardiff.” The Ely Mills were owned by Thomas Owen and Company Limited, a company which Perks had registered in March 1892, and of which he was chairman from 1898 to 1909 — having been on its board of directors since 1892. It seems strange that Crane makes no mention in this book of the Thomas Owen company, one of Britain’s biggest paper-manufacturing firms of this period.

[21] Perks departed from Liverpool on the “Adriatic” on 8 May 1907, accompanied by his wife Edith, his eldest daughter Gertrude, his son Malcolm and one maid (Sarah Page).The family arrived in New York on 17 May 1907. This was Perks’s first voyage across the Atlantic. The family departed New York (on the “Celtic”) on 27 June 1907 and arrived back in Britain on 5 July. On 9 August 1907, Perks sailed from Liverpool for Quebec on the “Empress of Britain”, arriving on 16 August. He landed back in England (at Plymouth) on 2 October 1907.

[22] Shortly after his return to England from the first of his two visits to Canada, The Sheffield Independent carried a report in its “Special London Letter” column which included: “[Mr Perks] has journeyed the whole length of the proposed canal, from Georgian Bay through Lake Nipissing … He has run the Rapids and been nearly burnt in a forest fire” (The Sheffield independent, 8 July 1907, p. 5). This seems to suggest that the “narrow escape from a forest fire”, which Crane proceeds here to give a fairly lengthy account of, occurred on Perks’s first visit to Canada.

[23] The Royal Commission on London Traffic was established in February 1903 and issued its report on 17 July 1905. Perks gave evidence before the Commission on 17 March and 18 March 1904, those being the 47th and 48th days of the Commission’s hearings.

[24] The interview Crane cites here appears to be the one Perks had given in Louth to “one of his constituents”, published in The Sheffield Independent of 10 October 1907 (at p. 6). There, the passage read: “Mr Perks said it was sometimes assumed that English railways belonged to a few wealthy capitalists. That was not the case. The stock was held by a multitude of small investors whose average holding did not exceed £1,000. Very large quantities of stock were held by the insurance companies and the friendly societies, who had invested on the British railways the savings of the working and middle classes.” Interestingly this paragraph immediately follows the passage which Crane quotes two pages later on pages 93 and 94.

[25] This is a slight exaggeration of the plight of the holders of ordinary shares in the Metropolitan District Railway. For the four calendar years 1879 to 1882 inclusive, the company managed to pay its ordinary shareholders modest dividends in respect of six out of the eight half-years. But at the time Crane was writing, the three-eighths of one per cent per annum paid in respect of the first half of 1882 was the most recent occasion on which the District’s ordinary shareholders had received anything at all on their shares.

[26] Richard Bell (1859-1930) was general secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants from 1897 to 1909, and President of the T.U.C. in 1904. He was elected to the House of Commons at the 1900 general election, being one of the first two Labour M.P.s to be elected following the formation of the Labour Representation Committee in February 1900. (The other was Keir Hardie).

[27] The interview Crane quotes from here was published in The Sheffield Independent of 10 October 1907 (at p. 6) under the heading: “Great Railway Crisis. Advice to Directors. A Sane Policy Outlined.” It was introduced as being an interview Perks had given in Louth to one of his constituents shortly after his return from his second visit to Canada. This piece was reproduced in full in a number of provincial newspapers. The paragraph immediately following the passage Crane quotes here was also used by Crane in writing this chapter. See note 24 above.