Chapter 7: The Million Fund and the Methodist Brotherhood

A scan of the original unannotated document can be accessed from the HathiTrust Digital Library collection at

The Life-Story of Sir Robert W. Perks, Baronet, by Denis Crane.

[start of page 140 in original pagination]

Chapter VII: The Million Fund and the Methodist Brotherhood

The greatest episode, however, in Sir Robert’s life as a Methodist, was the inauguration and completion of the famous Twentieth Century Fund. Of this great undertaking he himself has written: ‘It absorbed nearly three years of my time, and was the most arduous, anxious, and successful religious or philanthropic enterprise in which I was ever engaged.’[1]

This is not the place to attempt a history of the fund, but so closely was it interwoven with Sir Robert’s life that considerable space must be devoted to it. Briefly, the movement was intended as a fitting celebration of the dawn of a new century, by a Church anxious to vindicate at once its devotion, and its

[start of page 141 in original pagination]

determination to keep abreast of the progressive movements of the time. The method adopted was the raising of one million pounds, afterwards changed to one million guineas so that the odd shillings might cover expenses. The fund was to be divided among various departments of church work then existing, as well as to promote new enterprises which lack of means had hitherto delayed. Among the latter, the most conspicuous was the erection of a monumental building, which, while serving as the Connexional head quarters and a centre of evangelistic and social effort, might also be a suitable rendezvous for Methodists from all quarters of the world.

This huge scheme, though necessarily dependent for its development and execution upon the sagacity and toil of other men, appears to have originated exclusively in Sir Robert’s own fertile brain, and certainly owed more to his financial genius, extraordinary penetration, and dauntless optimism, than to the mental and moral qualities of any other man. But even in his own mind the idea developed gradually. It was first broached, somewhat indefinitely, at a private dinner-table at the Leeds Conference of 1897, when

[start of page 142 in original pagination]

it made a favourable impression on some of the Connexional leaders, who happened to be present. It was further mentioned in the Representative Session of the Conference, during a discussion on the proposed sale or reconstruction of the Mission House-project to which the want of adequate denominational head quarters gave special urgency. Fearing that this step would postpone if it did not finally defeat his larger scheme, Sir Robert at first opposed it. But when it was shown that the rebuilding of the Mission House was necessary in any case, his fears were over-ruled.

His great proposition now began to be freely discussed throughout the Connexion, but for some time he took no action, hoping, as he says, that some one else would assume the onus of carrying it through. A new fillip was given to the matter at a meeting of ministers and laymen in the following November, when the spiritual needs of the metropolis were under consideration. Some one had urged that only by the creation of a new and special fund could the spiritual destitution of the rapidly growing London suburbs be relieved, and had proposed that twenty-five thousand pounds should be

[start of page 143 in original pagination]

raised for this purpose. This proposal also, and for the same reasons, Sir Robert regarded with disfavour, and he seized the opportunity yet further to detail the advantages of his own project.[2] With a view to elucidating certain points, he afterwards accorded an interview to The Methodist Recorder, and the dissemination throughout the country of the information thus imparted made the scheme the topic of the hour.[3]

Evidently the movement was inspired from above. Satisfied on this point, he at once set to work to prepare a definite plan of campaign to present to the following Conference. He endeavoured to secure in advance a list of ten thousand persons who, in the event of the scheme being adopted, would be willing to act as stewards. This step, taken before the Conference had had an opportunity of considering the matter, was regarded in some quarters as premature ; but this was one of those occasions on which Sir Robert’s faith in ‘glorious irregularity’ justified itself. The boldness of the whole thing had captivated the Connexional imagination, and everywhere young and old were eager to give it enthusiastic support. He foresaw that such a strong and

[start of page 144 in original pagination]

growing body of opinion the Conference would be unable to resist. So powerful, indeed, was the feeling, that rival interests were impotent to check it, and on January 31, 1898, he was asked further to expound his views before the London Methodist Council. At this meeting the broad issues only were discussed, and so far from attempting to rush an immature scheme, or to force the hand of the Conference, he affirmed his willingness to put his own proposals aside and give his hearty support to any better ones that might be adduced. At the same time, he stated that out of nine hundred and nine superintendent ministers to whom he had appealed, only fourteen had disapproved of his taking action before Conference had sanctioned the scheme, while seven hundred and eighteen had urged him to proceed.[4]

When Conference met, the ‘Million Fund,’ as it was now called, had already engaged the attention, not merely of Methodists, but of the whole religious world ; and Congregationalists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and even Anglicans, were contemplating the inauguration of similar movements. Probably no fund of any magnitude has ever been launched with fewer dis-

[start of page 145 in original pagination]

sentients, and up to this point, at least, not a solitary letter, so said the denominational organ, had been received raising objection to the scheme. It was on Monday afternoon, July 25, in Great Thornton Street Chapel, Hull, that Sir Robert introduced the matter, in a speech marked by great simplicity and a deep sense of the gravity of his proposals. A fact of excellent augury was that, instead of the wild cheering which sometimes marks the initiation of popular movements, the Conference gave that quiet, earnest attention to every detail which the magnitude and importance of the undertaking deserved.

The fundamental idea of the fund, which differentiated it from every other in the history of Methodism, was enshrined in the famous phrase, ‘A million guineas from a million Methodists.’ Asked on one occasion what suggested this principle. Sir Robert replied: ‘The fact that our three other great funds — raised respectively in 1839, called the Centenary Fund, when £250,000 was raised; in 1863, called the Jubilee Fund, when £200,000 was raised ; and the Thanksgiving Fund of 1878, when we raised nearly £300,000 — were contributed by comparatively few persons.

[start of page 146 in original pagination]

Towards the last, excluding public collections, only about sixty thousand persons subscribed[5]. My idea was to fall back upon John Wesley’s own plan of small contributions from the masses, rather than large sums from the wealthy.’

This shrewd appreciation of ‘the power of the penny’ he derived from his fifteen years’ experience in connexion with the Metropolitan Railway, which in those days carried nearly ninety millions of people every year, at an average fare of three-halfpence, and yet paid a five per cent dividend. Arithmetical calculations on any large scale are the last things in the world to occupy the mind of the average Church leader. Sir Robert simply applied an extraordinarily acute business method to religious affairs, the basis of his calculations being a computation of the aggregate wealth and savings of the Methodist people. His affirmations on this point have sometimes provoked criticism, but have never been disproved. He estimates the savings of Wesleyan Methodists during the last ten years at, roughly, one hundred million pounds. And to him it seemed reasonable, that for objects so worthy,

[start of page 147 in original pagination]

a modicum of this accumulating wealth should be freely surrendered at the call of the Church. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that the ‘one person one guinea’ principle was the one feature of the scheme which the Connexional leaders at first found difficulty in accepting; yet it was undoubtedly the real secret of the fund’s success.

There were, of course, other novel features which added greatly to the popularity of the scheme. Every person subscribing was entitled to enter his name upon a Historic Roll, to be preserved in the Church archives for the wonderment of future generations. No restrictions were imposed concerning Church membership; any one who himself, or whose friends, living or dead, had been associated with or derived benefit from the Connexion, might give his guinea on his own or their behalf. Nor need a donor limit his gift to a single guinea; he might give a hundred, or a thousand, if he chose; and for every guinea given he was entitled to enter on the Roll the name of a relative or friend ; but in no case was the amount of the subscription to be recorded[6]. A medal was also struck to commemorate the fund, one being awarded to

[start of page 148 in original pagination]

every child who gave or collected a shilling. By this novel means children who could not give or collect a guinea were included in the scheme and had a lasting memorial of it. On this point Sir Robert displayed a fine historic sense, for he foresaw what precious curiosities these medals will be a century hence.

The Conference over, and the seal of its approval given, the campaign began. Roughly speaking, a period of two and a half years had been assigned for the completion of the task, for it was hoped to obtain the whole amount by January 1, 1901[7]. The public inauguration took place at Wesley’s Chapel in November 1898, when the President of the Conference, the Rev. Hugh Price Hughes, who was a cordial supporter of the scheme, preached in the morning ; the Rev. C. H. Kelly, an Ex-President, presided over a conference on the aims and organization of the fund, in the afternoon; and Sir Robert took the chair at a public meeting at night. The gatherings, which made a profound impression upon the Connexion, were described at the time as ‘in the highest degree responsible and representative.’ The evening meeting, in particular, was memorable. Sir Robert, said a contem-

[start of page 149 in original pagination]

porary writer, ‘spoke like a man inspired. Many of his strokes were supremely happy. Above all, it was a godly speech, a speech that the saintliest of the old Methodist laymen, hearing about it in heaven, will thank God for.’

In the meantime, however, the promoters of the scheme had not been idle. The late Rev. Albert Clayton (the General Secretary of the fund), his eight honorary assistants, and Sir Robert, who was one of the five Treasurers[8], had been busily organizing meetings all over the country, preparing collecting books and boxes, and issuing pamphlets and all the other paraphernalia which such an effort required. Sir Robert himself wrote one of the first brochures, ‘How can I help the Wesleyan Methodist Twentieth Century Fund?;’ and followed it soon after by another, ‘Shall I sign the Methodist Historic Roll?’ The campaign was opened in the provinces by a big meeting at Oxford Place, Leeds, which was followed by others at Manchester, Newcastle-on-Tyne, and other large cities and towns. Everywhere the utmost enthusiasm prevailed. One of the most striking features of the meetings was their deep spiritual tone. Instead of being obsessed

[start of page 150 in original pagination]

with the monetary side of the project, the vast audiences kept steadily in view its moral and religious ends; a fact truly remarkable even when it is admitted that Mr. Price Hughes’s famous District Conventions for the deepening of the spiritual life contributed not a little to the happy result.

As usual in such cases, the earlier part of the task was the easier. The money came in at first with great rapidity. At the inaugural meeting seventy thousand guineas had already been promised, and further gifts poured in at the rate, on an average, of £4,000 a week. But by the following Conference the stream had begun to grow sluggish. Three hundred thousand guineas had still to be raised. Now, for the first time, the voice of the doubter was heard in the land. It was urged that the time had come to depart from the original principle and for the rich men of the Connexion to save the situation. All kinds of stories were current in the Press. One rumour had it that a single family was going to give a hundred thousand pounds; another, that three brothers had promised a like amount. Some stated that Sir Robert himself was going to subscribe the last hundred

[start of page 151 in original pagination]

thousand. Against such proposals the founder of the fund resolutely set his face[9]. He pointed out that when the million guineas had been subscribed and the various new enterprises had been started, large sums would still be needed for their maintenance. Let the rank and file, he urged, contribute this initial million ; then the wealthier classes could be relied on for the support of the new schemes when they had been launched.

The difficulty of completing the fund was now increased by the outbreak of the Boer War, which not only monopolized public attention, but also, by its influence on trade and its numerous relief funds, drained the public purse. A Methodist War Relief Fund, indeed, ran contemporaneously with the Million Fund, the two subscription lists appearing side by side in the Methodist Press. Yet it is due to say that, in spite of these diversions of public support, in spite of the fact that the late Queen contributed a thousand pounds to the War funds, the Duke of Portland ten thousand pounds, an anonymous donor a similar sum, and scores of City men their hundreds of pounds, all the relief funds put together barely equalled the amount raised

[start of page 152 in original pagination]

by the Methodists towards their darling project in six months.

At the 1901 Conference[10], however, it was reported that, chiefly owing to the War, the fund was still £100,000 short of completion. Sir Robert therefore suggested that on the last Sunday in the year a simultaneous collection should be made in every Methodist chapel in the land, the ladies of Methodism to be in charge of it[11]. The effort proved a huge success, the amount realized, in new promises and cash, being about sixty-four thousand pounds, or nearly ten times the amount of an average Connexional collection. A curious incident occurred in the course of this effort. The amount of the collection at each place was communicated to head quarters by postcard. From one village chapel came the laconic message: ‘No preacher, no money.’ To Methodists who know anything of the vicissitudes of rural causes, the words will need no comment. This simultaneous collection, the largest ever made in Methodism, together with one or two substantial gifts — of which Sir Robert was ignorant — from wealthy laymen, at length brought the fund to a triumphant close.

[start of page 153 in original pagination]

When the final report was presented at the Conference of 1908 some interesting facts were brought out. The income in Great Britain was £1,005,258; in Ireland, £52,424; abroad, £16,000; making a total of £1,073,682. Of all that was promised, only £600 was lost through death or misfortune. The interest amounted to £89,216, which, of course, was added to the fund and is included in these figures.

But it was the sagacious and economical management of the fund which gave special delight to the Conference. The expenses were considerably less than the total of the shillings gained by turning the sovereign subscription into a guinea one ; and although the period covered by the fund was one of unexampled commercial depression, when Consols fell from 108 to something under 90, not one single penny of capital was lost through bad investment, while an average rate of interest of about 3 per cent was earned throughout the whole period. This remarkable good fortune was due in an especial manner to Sir Robert’s careful financing; a fact which the general public was not slow to recognize. The Westminster Gazette did not overstate the case when it said, in commenting on the report: ‘No

[start of page 154 in original pagination]

religious denomination has ever had a more capable and successful Chancellor of the Exchequer than the Wesleyan Methodists in Sir Robert Perks.’[12]

Thus, then, was this daring venture in what he once called ‘democratic Church finance,’ amply justified. But it was justified not in its monetary success alone. It did more than any other enterprise had ever done to direct public attention to the magnificent work of the Methodist Church; to strengthen the loyalty of the youth of Methodism, and to stimulate the Connexional spirit, which is unquestionably one of the main causes of the denomination’s progress. The sacrifice and heroism it called forth must have astonished even those who knew Methodism best. Young and old of both sexes, and people of all ranks of society, vied with each other in generosity and devotion. Ministers gave a magnificent lead, one, for example, sending fifty-three guineas for himself and family. But the real triumphs came from the very poor. The first subscriber in one provincial town was an old man over eighty, who lived in an almshouse on an income of about six shillings a week. He paid his guinea, and desired his name to be

[start of page 155 in original pagination]

entered on the Roll as ‘A Friend.’ Another case was that of a woman in the north ninety-one years of age, who spent weeks learning to write her name, so that she might herself inscribe it on the Roll. As an instance of generosity at the other end of the social scale, and from one whose connexion with Methodism is somewhat problematical, may be mentioned the case of Lord Rosebery, who contributed a hundred guineas and declared his intention not only of entering his own name, but also of picking out ninety-nine Methodist children living around his country seat and having their names put in[13]. On this romantic side of the matter Sir Robert enlarged in one of his stirring pamphlets:

‘What strange names,’ he wrote, ‘what divers ranks, stand side by side! The inmate of the workhouse and the peer of the realm, statesmen and errand-boys, the millionaire and the tiny waif just rescued from the streets into the Children’s Home, the city mayor and the village labourer. Here is the trembling signature of the aged saint one hundred and seven years old, “afraid she won’t live many more years”; and there on the Roll is the name of the little lassie whose feeble hand

[start of page 156 in original pagination]

mother guided before her little child passed to a better land. What family reunions! “We have not done anything together for years,” said a rugged, tender-hearted Yorkshireman some months ago, “until my children and the missus and I signed the Roll.” ’

But the campaign was not without its humours and curiosities, too. A north-country minister, who had learned more than usual caution in circuit matters, rose in the central meeting and promised for his circuit one hundred and fifty guineas. At that moment he had in his pocket definite promises for a hundred and forty-nine! Among the good influences of the fund upon the Connexion was that it liberalized many who hitherto had not realized their power to give. In a south-country district the superintendent applied to the trustees of a village chapel for means to purchase for their own pulpit a new hymn-book. But, oppressed by the necessities of the chapel and the scantiness of its resources, they shook their heads. Yet when the Twentieth Century Fund came round, this little village promised thirty guineas. Shortly after, the trustees met their minister, and one of them

[start of page 157 in original pagination]

said: ‘Now, friends, we will have a new hymn-book, and we will pay for it ourselves, and here is my shilling towards it.’ They had found new courage under the uplifting and liberalizing influence of the fund.

Sir Robert’s own contributions to this great movement were twofold. His monetary gifts were large. One of the officers of the fund computed them at over ten thousand pounds[14]. To encourage the children at Bayswater he promised to put ten shillings on the card of every child in every Sunday school in the circuit, so that they might feel they had something with which to start collecting. To the supplementary fund alone, which rounded off the million guineas, he contributed a hundred additional guineas for himself and a like sum for every member of his family[15]. And he was as earnest in begging as he was generous in giving. He tapped the purses of his business friends. One day, in the office of a well-known firm of foreign and colonial bankers, he discovered that one of the chief officials had been a Methodist, years before, in the Colonies, and on that ground he demanded five hundred guineas — and actually got one hundred. Another acquaintance,

[start of page 158 in original pagination]

a keeper of race-horses, was one day in Sir Robert’s office. This man’s mother had been a Methodist, and when he was reminded of the fact he promised ‘something considerable’ towards the fund. But that was not good enough for Sir Robert. ‘We do not like these generalities,’ he said, ‘what do you mean by “something considerable”?’ ‘Well, at all events,’ the man replied, ‘I will promise you more than a hundred guineas.’[16] A similar sum was also extracted from a lady on the ground that ‘quite accidentally one of her children had been baptized long ago by a Methodist preacher.’

But Sir Robert’s gifts of time and strength were of even greater value. It will not be invidious to say that from first to last his was the predominant personality in the movement. That all the officials, as well as thousands of obscurer workers, laboured heroically, is a matter of common knowledge; no one man, no score of men, could have run so great an enterprise without the ceaseless and self-sacrificing co-operation of agents in every circuit in the Connexion. For his friend and colleague, Mr. Clayton, he had ungrudging admiration. Their relations were

[start of page 159 in original pagination]

never anything but cordial, and Sir Robert paid many a eulogy to the tremendous labour his friend devoted to the work. But when all is said, Sir Robert’s position was unique. He had his vast business interests to watch, his numerous social engagements to keep; yet for more than two years he practically placed himself at the disposal of the committee to be sent wheresoever it listed. And it was by no means easy to decide whither he should go, for it was the general demand, when a mass meeting was arranged, that he should be one of the speakers. Indeed, invitations came from as far afield as Johannesburg and New York. The Methodist Episcopal Church in the latter city invited him to address a great thanksgiving meeting, at which President Roosevelt was also to speak, in celebration of the completion of the American fund. During the whole of this strenuous period, it is alleged, he missed at most only some five or six engagements.

Sir Robert, however, would be the first to admit, that for all his labours he found full recompense in his increased knowledge of the Methodist people, in the secure place he won in their affections, and in the appreciable

[start of page 160 in original pagination]

improvement of his platform gifts. Concerning this last point an amusing incident is related. At the 1904 Conference, the Rev. C. H. Kelly, in moving a vote of thanks to the two chief agents of the fund, referred to the law of compensation, and declared that the recompense in Sir Robert’s case was that ‘He had become a very much better speaker than when he took up the work.’ But in replying to the vote Sir Robert got his own back. He told how at one of the meetings there sat on his left an aged preacher, who was so moved that he interrupted his peroration by shouting ‘Hallelujah!’ Sir Robert asked him afterwards how he dared do such a thing. He replied, ‘I have not shouted “Hallelujah” for twenty-five years.’ ‘ So,’ added Sir Robert, with a mischievous twinkle, ‘if the Million Fund has improved the speaking power of the laymen, it has also rejuvenated some of the ministers.’

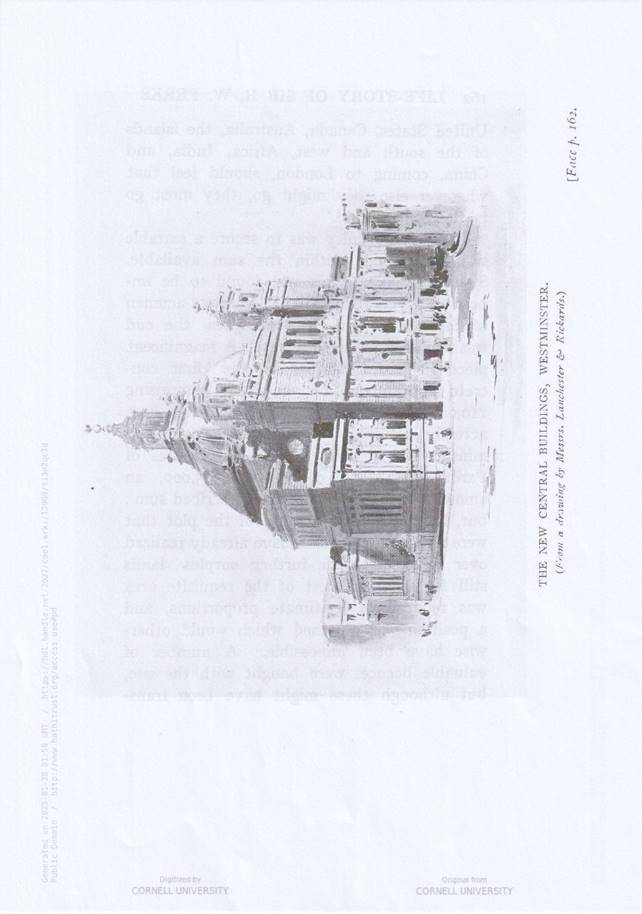

This subject ought not to be concluded without a further reference to one essential feature of the scheme. I allude to the new Connexional buildings at Westminster, the negotiations over which have from the first reflected his mind and financial genius in a

[start of page 161 in original pagination]

remarkable degree. Strange to say, the proposal to set apart a portion of the fund for this object was at first received with some misgiving. Stranger still, it may seem, the chief criticism came from London itself. Yet a little reflection will show the reason. ‘If,’ said a writer, while the question was still in its infancy, ‘if we were to regard the matter purely in the light of the work and well-being of London Methodism, we would rather spend the quarter of a million sterling in building a number of halls, or in creating new circuits in the outlying populations. It is from a Connexional point of view that this part of the scheme shines out as just, prudent, and in the highest and noblest sense of the term, statesmanlike. We do not want an ornamental building which may occasionally be turned to great uses; we want a building large, conspicuous, in the centre of metropolitan life, every square inch of which may be in constant use all the year round for the glory of God and for the salvation of the world. We would like this house to be so used every day of the week, that all who are most earnestly spiritual in the one Methodist Church in the

[start of page 162 in original pagination]

United States, Canada, Australia, the islands of the south and west, Africa, India, and China, coming to London, should feel that wherever else they might go, they must go to the Central Hall.’

The first difficulty was to secure a suitable site, at a price within the sum available. Strictly speaking, this was found to be impossible; yet, thanks to the business acumen of Sir Robert and his colleagues, the end was achieved in another way. A magnificent piece of land, described as the ‘first concrete appearance’ of the fund, comprising 110,000 square feet, or nearly twice the area actually needed, was acquired, facing Westminster Abbey and close to the Houses of Parliament. The cost was £335,000, an amount far in advance of the prescribed sum; but, by the sale of portions of the plot that were not required, which have already realized over £200,000 — with further surplus lands still for sale — the cost of the requisite area was reduced to legitimate proportions, and a position was obtained which would otherwise have been impossible[17]. A number of valuable licences were bought with the site, but although these might have been trans-

[start of page 163 in original pagination]

ferred at a considerable financial advantage, they were allowed to drop, in deference to the well-known principles of the Methodist people.

Lovers of the curious will find pleasure in the fact that by the purchase of this site Methodism regained in the City of Westminster a foothold which years before she had been compelled to relinquish. On the land at the time of the purchase stood a place of public entertainment, of doubtful reputation, known as the Royal Aquarium. This, of course, has since been demolished. But at a famous meeting held there in February 1903, to commemorate the purchase, it was whispered that on that same ground, many years before, had stood a small Methodist chapel, and that at a subsequent period a Wesleyan Methodist service was held on the spot for the benefit of Army recruits.

Public interest in the new building has been widely reflected, far beyond the limits of these shores. Inquiries as to its progress have come from all quarters of the world, and from American Methodists in particular. During his recent tours in the States and Canada no question was put to Sir Robert

[start of page 164 in original pagination]

more frequently than this: ‘When will your great building at Westminster be ready?’[18]

The new hall, which will be one of the most monumental and imposing edifices of its kind in the world, will provide, in addition to all the usual features of a Church’s head quarters, a library, representative of all that is best in modem literature and singularly rich in Methodist lore. Here will be preserved, sumptuously bound in fifty volumes, the Historic Roll, with its wonderful record of names. Future Methodists, however eagerly they may search therein for the autograph of forefather or relative, will not fail to linger a moment over the pages devoted to the Bayswater Circuit, where will be found, numbers thirty-one and thirty-two on the list, the names of Robert William Perks and Edith Perks, followed by those of the various members of their family ; and, a little lower down, in the same strong hand, those of George Thomas Perks and his wife, inscribed in grateful and loving memory[19].

Sir Robert’s latest scheme is one in every way worthy to rank with that of which I have just spoken. It is nothing less than to gather into one great brotherhood for mutual help

[start of page 165 in original pagination]

the federated forces of Methodism throughout the world. All through his Methodist life, he once confessed, the thought of something of the kind had been at the back of his mind. The urgent appeals for assistance in one form or another, which he, like every other wealthy Methodist, almost daily receives from distressed members of his Church, helped perhaps more than anything else to give definite shape to his plans. What he as an individual could not do, the Methodist Church collectively, he thought, could easily accomplish.

The question appealed to him in a distinctly philanthropic form. ‘Is modern Methodism, he asked, ‘living up to the standard set us by John Wesley, in using the influence, the wealth, and the energy of our Church, for the social as well as the spiritual well-being of the people?’ Relying on ‘that all-pervasive and strange something’ which creates a sense of mutual confidence between Methodist and Methodist all the world over, he suggested to the Conference of 1907 that there were four main fields in which Methodists might use their collective strength for the common good — Emigration, Employment, a Loan Society, and Provision for Old Age[20]. State pensions

[start of page 166 in original pagination]

having since been established, the last-named feature has, of course, been dropped, while the question of loans is being held in abeyance.

The proposals in general were well received, both at home and abroad. Shortly after he had expounded his plans to the Methodist public in England, he had an opportunity of laying them before the Methodist Church of America. ‘Without exception,’ he wrote, ‘they hail with enthusiasm the formation of such an international bond of Christian unity and service.’

His claims as to the ubiquity and business ability of Methodists — two facts largely relied upon for the success of the scheme — received interesting confirmation on his outward journey to the States. No sooner had he stepped aboard the steamer at Liverpool than he met a Methodist of outstanding capacity in the London manager of the ‘White Star’ line. A young doctor on board, whose services happily were not needed, proved to be another good Methodist. The chief official of the customs at New York turned out to belong to the same community; while on going to the offices of the shipping company to arrange his return passage, he discovered that the

[start of page 167 in original pagination]

head man there was again a Methodist. Even at an up-country station, the telegraph girl asked, as he handed in a wire: ‘Are you Mr. Perks, the Methodist, from England?’ and added, ‘I, too, am a Methodist. Mother came to Canada before I was born.’ And so it was everywhere. Farmers, bankers, business men, store-keepers, politicians, professional men — every class had its prominent representatives in the Methodist ranks; and, said Sir Robert, ‘they were as a rule a thrifty, thinking, up-to-date, God-fearing race.’

A scheme which aims at giving a new practical significance to this vast religious freemasonry, and which makes a point of looking after the social and spiritual welfare of Methodist emigrants (of whom, by the way, there were nearly ninety aboard the vessel by which Sir Robert crossed to the States) for ever trekking towards the untried West is not likely to prove abortive ; and the definite scheme of working now being devised by an influential committee is awaited by the Methodist Church throughout the world with eagerness and hope.

End Notes to Chapter Seven

[1] This sentence is from page 98 of Perks’s article “My Methodist Life” published in the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine, Volume 129, 1906, pp. 94-98.

[2] The meeting Crane refers to here appears to be that of “The Committee on Methodist Aggression in London” held on 2 November 1897. The report of this meeting published in the Methodist Times included the following: “Mr. Walford Green said that if the Committee had to deal effectively with the problem before it, it would be necessary to raise a Special Fund to supplement grants from the Metropolitan Chapel Building Fund in localities which were outside circuits and where we had no adequate resources, although the population was large or rapidly increasing. … Mr. Price Hughes proposed the appointment of a small committee to consider the possibility and desirability of creating such a Special Fund as had been proposed. At this point Mr. Perks stated that he was in some doubt whether such a Fund should be raised in London, as it might interfere with the creation of a very much larger Fund which he had been contemplating for some time. His own idea was that we should prepare for the 20th century by raising a fund of One Million sterling, and that this could be most easily done if every English Methodist gave or collected one sovereign. He intended, all being well, to make some such proposal at the next Conference.” (The Methodist Times, 4 November 1897, p.760). Note that at this stage Perks was talking in terms of pounds rather than guineas.

[3] The “interview” Crane refers to here was published in the issue of The Methodist Recorder dated 11 November 1897. Perks here talks in terms of guineas, and indicates that the proposed timetable was for the million guineas to be “subscribed by 1 January 1900.” That wording, it should be noted, does not mean that all of the money was to be handed-over by that date. Rather it was by that date that the commitments, or promises, were to be made.

[4] At this meeting held at Centenary Hall, Bishopsgate Street, on 31 January 1898 Perks spoke at some length on what he saw as the defining feature of his scheme — a feature which he later was very keen not to back down from. The report in The Methodist Times on this was headed “A Democratic Quality”, and read: “The great feature of the scheme, the novelty of the proposal, Mr. Perks proceeded to explain, lies in its universality. Every Methodist could have a share in it; it was one pound from one person that lay at the root of the scheme. This gave it a democratic quality, for which the speaker quoted the authority of John Wesley, who speaks in his ‘Journal’ of the ‘penny a week, shilling a quarter’ principle of Methodist finance as peculiarly democratic. But this principle would not deprive rich Methodists of the luxury of giving … Mr. Perks indignantly denied that it was an ingenious scheme for letting off rich laymen, for a charming feature about it was that it left your rich laymen to be tapped ad infinitum for circuit enterprises.” (The Methodist Times, 3 February 1898, p.65).

[5] The more recent statistical work carried out by David Jeremy sheds additional light on this. At the time the 1878 Thanksgiving Fund closed, the number of members of the Wesleyan Methodist Connexion was 407,085. Jeremy’s estimate of the number of donors to that fund was 57,381 or 14.1 per cent of the membership figure. The equivalent figures for the two earlier Wesleyan Funds were: 36,395 donors from 342,380 members (10.6 per cent) in the case of the 1863 Jubilee Fund; and 46,791 donors from 436,109 members (10.7 per cent) in the case of the 1839 Centenary Fund. See p.196 of David J. Jeremy, “Who were the Benefactors of Wesleyan Methodism in the Nineteenth Century”, Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Volume 61, Part 5 (May 2018), pp.186-200.

[6] Perks regarded this point as an important matter of principle regarding the scheme. But it was later “diluted” in some respects (see notes 9 and 10 below).

[7] The date 1 January 1901 had been settled upon in recognition of it being the first day of the new century. The logic behind this was that the first year of the Christian era was 1 A.D., there having been no “year zero”, and accordingly the first day of the second century would have been the first day of the year 101, and so on. The aim was that the one million guineas of subscriptions should be secured by the opening day of the new century, with the possibility of some leeway regarding the actual handing-over of monies to be allowed for beyond that date.

[8] The five Treasurers were four laymen plus one minister — the latter being the Rev. Walford Green (referred to earlier in note 2 above). The eight Honorary Secretaries were four laymen and four ministers. The constitution of the Fund specified that the general secretary should be “a minister set apart for this work.” Albert Clayton (1841-1907) was later elected President of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference (in 1906).

[9] Crane is correct when he states that Perks “resolutely set his face” against departing from the principle of one person one guinea, and resorting to appeals to “the rich men of the Connexion to save the situation.” But Crane misleads his readers when he implies here that Perks was successful in taking that stance both at the W.M. Conference of 1899 and at that of 1900. At the 1899 Conference Perks appealed eloquently to his fellow representatives “to adhere resolutely to the cardinal principle upon which this Fund rests — one person one guinea.” And on that occasion the principle was maintained in place (see The Methodist Times, 27 July 1899, pp.505-506). But at the July 1900 Conference, things went differently. When Perks stood to move the motion to receive and adopt the report of the Twentieth Century Fund, he said: “Mr. President, the work of the last year has not been sensational.” His message was that a redoubling of effort was called for, and to stick to the agreed approach: “I beg that you will work with greater zeal, with greater skill, and with greater assiduity the principle of one person, one guinea …”. (The Methodist Times, 2 August 1900, p.530). Perks’s seconder, ex-President of the Conference¸ F.W. MacDonald, was more equivocal: “I have never understood, neither do I understand now, what is meant by the phrase ‘one person one guinea.’ Nevertheless, I have given several explanations of it which, if Mr. Perks will allow me to say so, were at least as luminous and effective as his own. … Sir, there is nothing fixed, stereotyped, mechanical, about this expression ‘one person one guinea’. It means anything you like, and the more the better. (Laughter)” (loc. cit.) That paved the way for Hugh Price Hughes to make a call for: “some inspiring examples today … I have been wondering whether, for the final effort that is necessary, five persons could be moved to give ten thousand guineas each, and ten to give five thousand each.” The President then called on Joseph Rank, the wealthy miller, to speak. Following the cue from Hugh Price Hughes, Rank volunteered to increase his donation to the Fund by 10,000 guineas. And he went further, saying he would also give the last 10,000 guineas required to achieve the Fund’s target. A sequence of other wealthy lay representatives at the Conference spoke, committing themselves to increase their donations, and this “Financial Love-Feast”, as it was described in the report of The Methodist Times, was resumed in the evening session of the Conference (op. cit., 2 August 1900, p.532 and p.534). It would seem that Perks was out-manoeuvred on this occasion. But Crane chooses to cast a veil across these proceedings at the W.M. Conference of 1900.

[10] In jumping to the W.M. Conference of 1901 here, Crane omits any mention of the meeting of the General Committee of the Twentieth Century Fund held at City Road in early December 1900. It was at this meeting that Perks made an explicit concession regarding the ‘one person one guinea’ mantra. He proposed that “a special list be opened that day for 1,000 donations of 100 guineas each.” In explaining this proposal, Perks said “this principle of 100 guineas each from 1,000 people would hit the ‘middlemen’ in Methodism”, and that “he did hope that the uniform character of the scheme would be preserved and that they would try to maintain the equality, not of the ability to give, but that equality of the actual gifts which distinguished the early character of the Fund” (The Methodist Times, 13 December 1900, p. 903). The “first list” of donations under this “Supplementary Effort to Complete the Fund” was published soon after Perks’s proposal had been approved. The first seven entries (at 100 guineas each) were R.W. Perks, his wife Edith, his four daughters, and his eight-year old son Malcolm (ibid, 13 December 1900, p. 905).

[11] The suggestion Crane refers to here had been made by York District Synod. But Perks gave it his endorsement, stating at the Conference: “I would like to call attention to a recommendation of the York District which is a sensible suggestion — that we should set apart the last Sunday of the year for an organised special collection in connection with the completion of the Fund.” (The Methodist Times, 25 July 1901, p. 513).

[12] This statement appears in The Westminster Gazette of 17 July 1908, p. 2.

[13] It was in his speech regarding the Twentieth Century Fund to the W.M. Conference of 1899 that Perks made public this donation from Britain’s ex prime minister. Perks told the Conference: “I had a letter from a distinguished friend of mine a day or two ago, a friend distinguished in this country, who has held high offices and served the Queen. He sent me 100 guineas and he said that he was going to write his name on the Roll. I never asked him for a penny. He said he was going to pick out also ninety-nine Methodist children round about his country house, and see that their names were put on the Roll. That man was the late Prime Minister of England, Lord Rosebery (Cheers).” (The Methodist Times, 27 July 1899, p.506).

[14] I have not been able to discover Crane’s source regarding this figure of “over ten thousands pounds.”

[15] See note 10 above.

[16] I suspect that the keeper of race-horses who Crane describes here as Perks’s “acquaintance”, was actually Perks’s first cousin Murray Griffith — whose mother was Rebecca, the only sister of Perks’s father (see note 24 to Chapter One). In the “first list” of donors to the “Supplementary Effort to Complete the Fund”, the ninth entry is Mr. Murray Griffith. He comes immediately after the seven entries for Perks’s immediate family and the entry for the parents-in-law of Perks’s brother. Moreover Perks noted that the 100 guineas from Murray Griffith was “in honour of his mother.” (The Methodist Times, 13 December 1900, pp.904-905).

[17] The provisional agreement for the purchase of the Royal Aquarium site was made on 18 July 1902, and Perks stated this publicly on 23 July 1902 (The Methodist Times, 24 July 1902, pp.505-506). There appear to have been some add-ons to the originally agreed price of £330,000. Perks told the 1907 W.M. Conference: “The net cost of the site was £360,000; that was a large sum, but a portion had been disposed of to Messrs. Holloway for £100,000; another portion was disposed of for a similar amount; and the tenant of the Imperial Hotel had given notice to terminate her lease, so they would have that part of the property — including the theatre, which they were compelled to buy — untrammelled. That was worth another £100,000, leaving them with a large piece of ground of 35,000 square feet, on which to build their great hall. That piece was worth from £220,000 to £225,000 and yet the result of that operation — call it what they would — (laughter) — was that it only cost them, after the sales of the other pieces some £60,000 to £70,000. (Cheers)” (The Daily Chronicle, 22 July 1907, p.6). The tenant of the Imperial Hotel referred to here was Lillie Langtry.

[18] At the time Crane was writing, completion of the Westminster Central Hall was still some way off. The Hall and associated “Connexional Buildings” were opened on 3 October 1912. The “artist’s impression” of the building, which is included in this chapter of Crane’s book, shows two towers which were part of the original design but which were never constructed. The nearby Westminster Hospital complained that the Hall’s dome and towers would darken their basement rooms in which medicines were compounded. In December 1909, after lengthy negotiations, Perks reached an agreement with the Hospital to settle the dispute. This included agreeing that the two towers would not be built.

[19] A transcript of these pages of the Historic Roll devoted to the Bayswater Circuit can be viewed on the website “My Wesleyan Methodists”. See Wesleyan Historic Roll, Volume 03, Second London District, London Bayswater Circuit 11. There are eighteen rows in the Perks sequence of the Roll that starts at entry 31: the first seven being for Perks, his wife and his five children; then two “in memory of” Perks’s parents; followed by four in memory of deceased sisters of Perks, including his married sister Elizabeth Volckman; and five for some of Elizabeth’s sons and daughters. The signatures of Perks’s brother George Dodds Perks, and his sister Flora can be found among the entries for the Bromley Circuit.

[20] Perks’s suggestions were set out in a pamphlet dated 9 August 1907 titled: “The Methodist Brotherhood: A Proposal to use the Federated Agencies of the Methodist Church in all parts of the world for the Mutual Help of Methodists.” A copy of this pamphlet is held at the John Rylands Library, Manchester University.