This article reproduced with kind permission from The Railway & Canal Historical Society.

Click the yellow journal cover image to access the full journal directly from their archive.

Perks signed his letter of resignation from the Barry board on 24 July 1890 and this resignation was accepted at the board meeting of 15 August 1890. His board seat was not filled by a nominee of the Perks group of first prefs holders, but went to Robert Forrest, Lord Windsor’s land agent in Glamorganshire.[114] The circumstances of Perks’ resignation cannot be described as amicable. These circumstances, as will be explained, arose from a marked deterioration in relations between T.A. Walker and the Barry company which seems to have commenced about March 1889, during the final months of the construction phase of the company’s dock and railway system. Subsequent to the Barry board meeting of April 1889, although Perks continued to serve the Barry company through legal and representational work in London, and via correspondence, he attended only one more board meeting (6 February 1890). And at that meeting the principal item on the agenda was the company’s escalating legal dispute with the executors of the T.A. Walker estate (Walker had died 25 November 1889). Perks was legal adviser to the three Walker executors.[115] As will be described, however, both during this final fifteen months of his time as a director of the company, and into later years, Perks remained on good and close terms with some of the Barry directors, notably John Cory and F.L. Davis.[116] This might imply that not all of the Barry board were entirely comfortable with the hard-line stance taken by Davies in the company’s relations with Walker from early 1889, and the continuation of that hard-line approach by Archibald Hood, Davies’ successor as deputy chairman of the Barry company.

Reference has been made in Section II to Walker attending the October 1887 meeting of the Barry board and complaining about “delays in the delivery of plans”. That might seem to suggest a poor state of relations had developed between Walker and Wolfe Barry during the first three years of work, on the project. But there is an alternative interpretation. It might simply represent Walker taking a considered and businesslike approach to his contracts, and seeking to ensure that the Barry directors were appropriately aware of the impact on the timetable for the work, of the significant alterations to the dock design that had been required in the wake of the drillings information obtained in mid-1885.

Some evidence that supports this second interpretation is among the documents held at the Lancashire Record Office in Preston, relating to Walker’s work on the Preston docks project. Walker’s concerns about the capital-funding for the Preston project have been mentioned already. But he also had professional concerns about certain features in the way the work was being directed and overseen by the Corporation-appointed engineer Edward Garlick (who had been Mayor of Preston when the Act for the docks had been promoted). For the new dock to be useable by ships of the draught it was designed to cater for, an appropriate channel needed to be dredged from the river at Preston, the Ribble, to the open sea. Garlick was pressing Walker to complete the dock, but was doing virtually nothing about dredging work on the channel. Walker’s view was that the product of this would be a non-operational dock which would itself be then silted-up by being so much “deeper” than the estuary bed between it and the open sea. Garlick was also refusing to certify that Walker had done the full “quantities” of work Walker was claiming, for monthly progress-payment purposes. Walker argued he was not being given a properly substantiated explanation of these differences. After months of trying to persuade Garlick to obtain advice from a better-qualified and more experienced engineer on these matters, in October 1886 Walker wrote to Walter Bibby, chairman of the Ribble committee of the Preston Corporation, to express his concerns.

At the end of that letter, Walker listed the seven biggest projects (in £ cost terms) he had “within the past twelve years constructed”, and stated:

On none of these Works have I had disputes on differences with the Engineers. The Works have been carried out and settled for without one disagreeable word, and I am sure all the Engineers for whom I have worked would corroborate this statement.[117]

The last of the seven major projects listed by Walker is “Barry Dock and Railways, now in progress for £1,000,000.” Thus Walker is saying here that at Barry things are progressing “without one disagreeable word” and he invites Bibby to contact Wolfe Barry to verify that.

The use by Walker of a twelve year time-frame for his projects in that October 1886 letter deserves comment. In January 1874, disagreement over work on the construction of a dock and channel at Garston near Liverpool led to litigation between the partnership of Walker and his younger brother Charles (the contractors) and the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) ─ which had accepted their £114,011 tender for the project in 1871. The completion date set in the contract was August 1873. Walker’s view was that the delays were largely because of “extensive and important alterations in and additions to the works as originally designed … made by Mr Baker, the engineer of the company, who also suspended some of the works for long spaces of time.” But the LNWR supported their engineer, took the work out of the hands of the Walkers, refused to pay out retention monies on the work already done, and so on. The Walkers sued. The case was heard in the Court of Common Pleas, during May to July 1876, and the decision went in Walker’s favour.[118] The LNWR appealed. In January 1877 the Court of Appeal confirmed the decision in Walker’s favour. At stake had been over £50,000, plus substantial legal costs.[119] This case was well known: The Times described it as “a case of great public interest” in December 1876. In 1886, therefore, Preston Corporation probably did not need to have it spelt out for them that on the last occasion that there had been “disagreeable words” over a major contract of his, Walker had been willing to back his own position against the most wealthy and powerful railway company in the country, in a protracted and costly legal struggle ─ despite being at that time much less experienced and much less wealthy than he had become twelve years later.[120]

Walker’s correspondence regarding his Preston docks contract suggests that over the first three years of his Barry contract there is nothing that would warrant the term “dispute” in relations between Walker and Wolfe Barry, or between Walker and the Barry company ─ and that such divergencies of view as are inevitable in any substantial and evolving contractual arrangement were being handled in the Barry case in a manner regarded by each of these parties as businesslike and acceptable. It is hard to see any shift in this tenor of things during 1887 and 1888. The Barry board minutes record that various letters from Walker were considered at various meetings, and by August 1888 a draft supplementary agreement with Walker was being discussed. Walker attended the board meeting of 17 August 1888 to discuss this further and the minutes record “the solicitor was instructed to prepare an agreement between the company and Mr Walker as suggested by Mr Perks ….”[121] Walker left England on 11 October 1888 for a four month visit to Buenos Aires. It is only from the time of Walker’s return from Argentina that relations between him and the Barry company appear to have become quite different in tenor.

Two main factors were probably in operation in bringing about this shift. The first was the ticking down of the clock towards completion of the construction phase of the Barry enterprise. Once the key elements of Walker’s work were completed, and things moved into a “tying up of loose ends” and preparing for operations phase, the incentive for the Barry board to be conciliatory on “divergencies of view” in order to maintain Walker’s goodwill became weaker. If Davies felt the board had been conciliatory (in these terms) to a high degree during 1887 and 1888, this may have been operating to predispose him for a reaction against Walker during 1889. The second factor is Walker’s health. Walker’s obituary in Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers states:

He had returned from a visit of inspection to the Buenos Ayres Harbour Works when the first symptoms of serious illness manifested themselves, and he gradually got worse, until his death from Bright’s disease, on 25th of November 1889.[122]

The symptoms of Bright’s disease, or nephritis of the kidneys, are described by John Franch in his recent biography of Charles T. Yerkes. Yerkes, who played a key role in a subsequent phase of Perks business career, died of this same disease in December 1905. From Franch’s account it is clear that the disease is both painful and very physically debilitating for the sufferer, except for periods of respite which become shorter and decreasingly “complete” as the disease progresses:

In the advanced phases of nephritis, the build-up of toxins in the blood severely disturbs the functions of all the body’s organs, including the brain. Delusions and hallucinations are two of the resulting symptoms.[123]

Franch goes on to say that during a period about six months before his death, Yerkes “began to fear that his servants were conspiring to poison him and consequently forced his valet, Arnold Held to taste his food for him before every meal.” But then some weeks later a respite period set in and for some time Yerkes seemed “almost fully recovered.”[124]

This factor of Walker’s health probably affected relations between him and the Barry company in two ways during the course of 1889. Focussing first on the respite periods from the disease’s symptoms, once Walker had been diagnosed and informed of the prognosis, his approach to matters concerning his contracts with the Barry company probably altered. There was no longer going to be as much time available to him to pursue a mutually agreeable resolution to divergencies of view over how much money the Barry company still owed him on the contracts. And there was a reduced incentive for him to step back from fully pressing for what he perceived to be his legal entitlements, for purposes of broader reputational and future contracts-winning-benefits. Turning to the non respite periods in the disease’s progress, Walker during those periods may have been prone to treating Davies with a high degree of mistrust and suspicion regarding the resolution of outstanding matters re his contracts. And this could easily then have led to “feedback loops” adversely affecting the approaches of both parties towards resolving those contract matters.

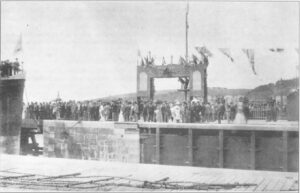

Relations between Walker and the Barry company deteriorated markedly during the course of 1889. Neither Walker nor Perks are recorded as having attended the ceremonial opening of the Barry dock on 18 July 1889 (to which 2,000 invited guest were conveyed by two special trains), or the official celebratory “luncheon” which followed. Walker’s obituary in the Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers stated:

At the opening of the Barry Docks, in the summer of 1889, it was noticed that Mr Walker was absent from the entertainment given by the Railway Company, to celebrate the occasion, and he was found presiding at a dinner he had given to his 2,000 navvies who he had determined should not be neglected on such a day.[125]

(R J Rimell (1923) History of the Barry Railway Company 1884-1921)

The fact that Walker missed the official Barry opening celebration and dined with his navvies appeared in a number of other obituary pieces, and has been picked up by various later writers seeking to provide a character sketch of Walker.[126] In all these cases the implication is that Walker had chosen to be in place x rather than place y. In fact Walker had been excluded from the official opening celebrations. He wrote to the Barry board complaining about this and his letter was considered at the board meeting of 15 August 1889. The exclusion had not been a decision of the board, but the board minutes are ambiguous as to whether it was the result of an executive decision (presumably made by Davies), or of a misunderstanding on the part of the police constables whose services had been employed by the company for the opening.[127] If it was the latter, and in light of Walker’s very high public profile in the area, it is hard to imagine how it could have occurred that such a “misunderstanding” was not overcome at the time. The obituaries of Walker in The Engineer and Engineering did not make any mention of the events at the Barry opening day, which might mean their writers were better informed about what had happened.[128]

Two weeks after the Barry directors had discussed Walker’s complaint about his exclusion from the official opening celebrations for the company’s dock and railway system, the company’s half-yearly shareholders meeting was held in Cardiff. Lord Windsor presided, but when a shareholder asked a question regarding the situation between the company and Walker, it was Davies who gave the reply:

He could not say what claim for extras Mr Walker might make against the company, but whatever he claimed, he would get very little. Seven or eight contracts had been made with him, and up to the last three months he had been paid in full every fortnight. How Mr Walker could make any claim, therefore, he did not know. They had already paid him a quarter of a million more than his contract.[129]

The Barry board meeting of 25 July 1889 had, in essence, made a decision to break off negotiations with Walker over his claims for “extras”, instructing the Secretary to inform Walker “that any claim hereafter made would be dealt with in the proper way”[130] ─ meaning the formal arbitration process specified in the contracts and supplementary agreements. Up to the final sentence of the Davies statement quoted above, he is simply saying that again, albeit in a fairly “confrontational” way, and in public. But the figure of a quarter of a million is intriguing.

At the time the Barry company set about constructing its dock and railway system, as was described in section I above, Walker was engaged to carry out two of the original four works contracts which covered the dock and rail infrastructure authorised in the 1884 Barry Act. The arithmetic of the company’s accounts is not compatible with Walker having been paid by August 1889 a quarter of a million (or anything that could reasonably be rounded to that figure) on account of alterations, additions, revised “quantity-estimates” etc. re those original two contracts. To sustain the Davies’ figure, it would be necessary to count a substantial part of the money paid to Walker on contract number 5, for the works authorised in the company’s 1885 Act, among the “extras” on the original contracts. Possibly this simply represents additional evidence of Davies’ apparent low regard for the merits of presenting shareholders with factually accurate information. But a second possibility is that Davies felt that the sum the board had agreed to pay Walker for contract five in February/March 1887, without going through a competitive tender process, had included some “compensation” to Walker for additional costs he was expected to bear regarding work on the dock not covered by the original dock contract or by formal supplementary agreements. For Davies to push such an argument in a confidential negotiation would be one thing. For him to expect to be able to argue thus in a formal arbitration process would be something quite different.

Such further dialogue as occurred between Walker and the Barry company between the end of August and November does not appear to have led to any “thawing” of matters over Walker’s claims for “extras” on his contracts with the company. The minutes of the Barry board meeting of 15 November 1889 record: “It was resolved that no further order for work be given to Mr T.A. Walker.” This suggests that Davies was not aware of how close to death Walker by then was,[131] and that the company’s correspondence with Perks (who had not attended a board meeting since April) had not led to Davies being alerted to this. Walker’s death on 25 November, with this dispute regarding his claims against the Barry company unresolved, put Perks in an even more difficult position than he had been in during the preceding months. The claims which had been “Walker’s claims” now became the claims of the Walker Estate, a trust entity created under Walker’s will, with Walker’s three executors having the legal duties and responsibilities attached to being its trustees. While Walker was alive (and in command of his faculties) he could choose to press his claims or to abstain from pressing them, to agree to a compromise or to choose not to compromise, all entirely at his own discretion. He could listen to his legal adviser’s views as to the pros and cons of various courses of action, but it was up to him whether to press for an “ambitious” definition of the extent of his claims, or to be more moderate/more conciliatory. With Walker dead, and carriage of the claims against the Barry company now the responsibility of the three executors, the situation was significantly different. The executors, with the legal duties of trustees, could not afford to behave as if they had the same degree of discretion available to them as is available to an individual managing his or her own affairs. Perks was legal adviser to the three executors. As none of the three had had any significant level of legal training, it was Perks’ professional duty to keep all three aware of their responsibilities, and of the risks of future legal actions being mounted against them by beneficiaries of the trust, should they be perceived to have been too moderate/too conciliatory in their carriage of the Walker Estate’s claims.

Once the Barry board had adopted the position that the Walker claims should be put into the formal arbitration process, therefore, and for as long as they adhered to that position, there was little that Perks as legal adviser to the Walker executors could do other than: to advise that the claims should be pursued; to help the Walker executors put together as good a case as possible to set out before the arbitrator; and to encourage that they pursue that case with due vigour. But was this compatible with Perks continuing in his capacity as a director of the Barry company?

During the first half of 1890 there was dialogue between Perks, acting in his capacity as legal adviser to the Walker trustees, and the Barry company over the arrangements for the forthcoming arbitration hearing. Matters discussed included limitations on the number of QCs each side should employ, limitations on the number of outside expert witnesses who would be called to give evidence and be subject to cross-examination, and so on. At Perks’ last attendance at a meeting of the Barry board there was discussion of whether the company was entitled to be represented in the hearings by the Attorney-General.[132] By the time the Barry board met on 20 June 1890, the Barry directors had lowered their sights. They resolved to propose “if the other side would agree,” that each side’s case should be put to the Arbitrator by its solicitor.[133] This looks as if it may have been a ploy to put pressure on Perks regarding his board seat. The same meeting resolved to make a series of counter-claims against the Walker Estate, and was held two weeks after a formal statement of the Walker claims had been lodged. Perks had simultaneously supplied details of these claims to the press.

Perks sent a letter dated 6 June to the South Wales Daily News (SWDN), which it published on 10 June 1890. This stated that the total sum claimed was £204,554 14s 5d, and that only £15,000 of this represented “retention” monies (which would already have been recognised as a liability in the Barry company’s accounts), indicating that the difference was for “extras” (and therefore not yet allowed for in the company’s accounts). In its next edition, the newspaper’s editorial stated:

comment was occasioned by the fact that Mr Perks, one of the directors of the company, is a member of a firm of solicitors acting for the executors against the company. It was, moreover, considered an extraordinary thing that the solicitors should write to the newspapers stating the fact of their claim.[134]

This editorial’s next paragraph goes on to outline the company’s reaction to the claim:

… it is self-evident that he [Walker] would not have allowed so large an amount as £190,060 to remain due upon extras without presenting claim for payment from time to time.

Looking at the two paragraphs together, it would seem reasonable to speculate that the source of the “comments” reported in the first was the same as the source of the “view” reported in the second, and indicates that a person who was speaking for a majority of the Barry directors was not happy with Perks’ conduct.

Perks’ response to the Barry board’s proposal that the leaders of the two sides’ cases before the Arbitrator should be their solicitors was reported to the Barry board meeting of 18 July 1890. Perks had stated that he declined to consent. According to the board minutes he cited among his grounds the public perception problems of a director of the company conducting a case against the company. This suggests that at the time Perks wrote that response he was intending to continue in his capacity as a director of the company. That letter must have been written at some point between 20 June 1890 and 18 July 1890, but on 24 July 1890 Perks signed his letter of resignation from the Barry board. One possibility is that Perks’ wording about the public perceptions issue was used by the majority group among the directors of the Barry company to put further pressure on Perks and that their “ploy” of 20 June had achieved the result intended. The size of the claim lodged may also have served to bring matters to a head. A week before the figure became public, Engineering reported that it was expected to be “a heavy claim … to exceed £100,000.”[135] Publication of the £204,554 figure led the South Wales Daily News to comment:

If they [the Walker executors] should succeed in their claim to the extent of only one half, £100,000 will be a heavy amount for the company to pay, necessitating doubtless, the calling up of more capital.[136]

These then were the circumstances in which Perks’ period as a director of the Barry company come to an end. Through his role as legal and financial adviser to the Walker executors, there was a continuation of interaction between Perks and the company until the formal arbitration process re the Walker claims had run its full course more than a year and a half later, in March 1892. The sole arbitrator was Wolfe Barry ─ as had been prescribed in the Barry contracts with Walker, and the thirteen months of hearings began in December 1890. During November 1890, serious discussions about a compromise to resolve the claims (and counter-claims) were held between Perks and Edward Davies (David Davies’ son who had been appointed managing director of the Barry company earlier that year). But these processes miscarried and led to further ill-feeling on the part of Hood (David Davies’ successor as deputy chairman), and a majority grouping among the Barry directors, towards Perks. Essentially Perks and Davies agreed that “subject to the approval of the respective parties”, the matters would be settled for £70,000.[137] The Walker executors agreed. The Barry board did not, and resolved to inform Perks in writing: “that the Board could not entertain the figures between him and Mr Davies, but that they would consider any reasonable proposal for a settlement.”[138] Perks chose to inform the press that this had happened, and the reaction at the next Barry board meeting was to break-off negotiations and resolve to contest the Walker claims (and enforce the counter-claims) with “every possible exertion.”[139]

This decision by the Barry board was reported the next day in the South Wales Daily News:

The Barry board has taken up their present attitude because of the peculiar circumstances under which publication has been made of the nature of the claim and of the negotiations designed to effect a settlement. It is a curious instance of business life to find a gentleman holding the position of director of an undertaking and at the same time acting as solicitor for parties making a claim against the company in which he holds that position, and afterwards publishing a statement which might be assumed to be detrimental to their interests. The natural indignation which the directors feel at the manner in which they have been treated in the conduct of this business finds expression in … [their decision] to push to the furthest limit the counter-claim which they set up against Mr Walker’s estate.[140]

The formal arbitration process concluded with Wolfe Barry issuing his decision in March 1892. This awarded the Walker executors £52,546, with each side to pay its own costs plus half of the Arbitrator’s costs. The Western Mail reported that the decision “extends to 25 closely-written folios”, and that the hearings had taken up about thirty full days.”[141]

Perks wrote to the Barry company stating that the Walker executors would claim interest on “the amount awarded from the date of the award to the date of payment.” The company’s cheque was sent and with that the period of close “interaction” between Perks and the company which had commenced in March 1887 came to an end.[142] The Barry board then seems to have got into a dispute with Robinson (the Resident Engineer) and Downing (the Secretary) over remuneration for the “extra services” they had rendered during the arbitration process. One imagines that if the Walker executors had been required to pay the Barry company’s costs, the Barry board might have been less vigorous in resisting Robinson and Downing’s claims.

It is interesting to consider a question at this point concerning the period before the formal arbitration process was commenced in December 1890. When Perks and Edward Davies held discussions about a possible compromise settlement, is it possible that the failure of those discussions was the result of Perks being either inept at such a negotiation process, or too preoccupied about issues concerning the legal duties of his principals as trustees (discussed above) to be willing to make the types of concession that are required for a mutually-acceptable compromise to be achievable? There is evidence to support the conclusion that both of these possibilities can be rejected.

Walker’s will provided for his executors to carry on the work on any of his contracts that were still in progress at the time of his death (unless they judged it better “to wind up or close or dispose [of them]”), but directed that they “should not enter into any fresh contract for works.” The two biggest contracts Walker was working on at the time of his death were those for the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal and for the port and harbour works at Buenos Aires. Both were complex and “evolving” projects requiring negotiations about payments for work additional to, or different in nature from, that covered in the original contract, as well as negotiations about other emerging issues. By the time of Walker’s death, six supplementary agreements to the original Manchester Ship Canal contract had been negotiated and signed, the last of these being dated 14 August 1889. As 1890 progressed there was need for further rounds of negotiation between the company and the Walker executors and the situation was rendered more difficult by it becoming questionable whether the Manchester Ship Canal company would be able to cover the increasing costs of the project within its authorised capital-raising powers, and whether it would be able to succeed in raising substantial further capital funds from private sector investors, even if it obtained parliamentary authorisation to do so.

To tackle the issue of the Walker executors’ legal duties as trustees vis a vis the benefits to be gained from their negotiating with a willingness to make compromises, Perks did something outside the usual, and something which bears testimony to the fertility and agility of his mind. He set about organising for the Walker executors and the Walker heirs to secure a private Act of Parliament. The “Walker Estate Act, 1891” received Royal Assent in August 1891 after progressing through its main stages in May and June.[143] The preamble to the Bill stated that among its objectives was to approve a settlement made between the Walker executors and the Manchester Ship Canal company on 21 November 1890, “if and so far as it is not within the scope of powers [conferred on those executors by the will].”[144] The November 1890 settlement referred to here was a complex one, but one feature of it was that the MSC company would pay to the executors £180,000 and they would accept that as a full settlement of the “upwards of £470,000” they had been claiming from the company in extras on the contract to construct the canal.[145] Perks attended the MSC company’s half yearly shareholders meeting held in Manchester on 3 February 1891. The company’s deputy chairman, Sir Joseph Lee, in his address to the meeting indicated that Perks was “the legal adviser of the [Walker] executors” and stated:

… throughout all the negotiations which lasted for so long a time the greatest good temper and cordiality was shown, and they were concluded to the satisfaction of all concerned.[146]

Perks returned this compliment when he spoke in favour of the vote of thanks to the chairman and directors of the company.[147]

In the middle months of 1890, the Walker executors had substantial claims against both the Manchester Ship Canal company and the Barry company. In the former case the claims were settled in November on a basis both sides appear to have regarded as acceptable. In the Barry case, that did not happen ─ and from the middle of December the majority group on the Barry board were complaining about the way Perks went about doing business. By no means should this be taken to indicate that the MSC board made a better decision that the Barry board. But it does seem to put pay to the possibility raised above that the failure of the negotiation between Perks and the Barry company can be attributed to Perks being an inept negotiator or to the Walker executors being excessively fearful over their legal responsibilities as trustees. If the Barry board had been willing to accept a settlement the Walker executors regarded as an acceptable compromise, that settlement could have been written into the Walker Estate Act in the same way as the agreement with the MSC company was (and as were various other agreements regarding the business activities passed on by Walker to his executors).

Perks himself was careful not to claim all of the credit for creating the novel business entity which the Walker Estate Act established. In his Notes for an Autobiography, he wrote:

Two courses were open to them [the Walker trustees] after Mr Walker’s death. One would have been to throw the whole estate into Chancery. Many trustees faced with like responsibilities would have adopted this course; had they done so they could have taken no important step without the permission and direction of the Courts of Law. This would have meant cost, delay, inefficiency, and probably disaster. At the same time they had to take action, and that quickly, and in many ways for which they needed some legal authority. They, therefore, applied to Parliament for Private Acts of Parliament which conferred upon the trustees wide powers to borrow and secure loans, to enter into agreements, to realise and develop properties, and generally to administer affairs with as much freedom as Mr Walker could have done had his life been spared.[148]

But, it seems reasonably clear that Perks played a more important role in the operations of the business entity which emerged from Walker’s death than this wording would suggest. Edwin Waterhouse (1841-1917), one of the founding fathers of modern accountancy, president of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales 1892-94, and accountant/auditor for the LNWR from 1861, worked with Perks on the third of the Walker Estate Acts, passed in 1898. In his memoirs, Waterhouse described the work as;

… an interesting matter entrusted to me by Mr Robert Perks, the well-known solicitor and MP, who had for years been a kind business friend. He was concerned for the estate of Mr Walker, the contractor, and had with extreme ability, and very much to the advantage of those concerned, carried on sundry contracts which were current at the time of Mr Walker’s death, the profits arising to many hundreds of thousands of pounds.[149]

Waterhouse’s wording suggests that Perks was more than simply “legal adviser” to the Walker trustees, but had taken on (with responsibility to those trustees) some important portion of the head office functions in the Walker organisation previously carried out by Walker himself. Although Walker had a number of trusted lieutenants in his organisation (including the three men he designated to be his executors), he does not appear to have made a practice of delegating significant authority. The obituary in Engineering stated:

… he managed all his vast undertakings as a captain fights his ship from the conning-tower. This was the weak point of his system, for it threw an enormous strain upon one human frame, and the result is that we have to mourn his death at the comparatively young age of sixty one.[150]

Under these circumstances, the Walker organisation must have come under stress during 1889, even before Walker’s health condition went into its final phase. During the periods that the Bright’s disease symptoms made it impossible for Walker to function effectively in the way he had become accustomed to, it may have been that Perks was called upon to play an expanded role in the running of the Walker organisation. By the time the claims for extras on the Barry contract were lodged in early June 1890, it was probably apparent to the directors of the Barry company that Perks’ role within the Walker firm had expanded. When Perks first joined the Barry board in mid-1887, he was the voice of the group seen to be the solution to the company’s biggest financial headache at that time, namely raising more capital. That financial headache had abated with the completion of dock and rail system, and the continued boom in coal demand. But Perks was still on the Barry board in mid-1890 and now appeared to be the voice of the group who were the “cause” of the company’s biggest financial headache of this time, the £204,554 claim. It is understandable that at least some on the Barry board would have viewed Perks in mid-1890 as someone who had become dispensable as a director of the company.

The articles from the South Wales Daily News during 1890 cited earlier suggest that Hood ─ supported by a sufficient number of the Barry board members to give a majority ─ had taken umbrage at Perks’ methods of conducting business matters, at least vis a vis themselves. What evidence is there to suggest that this was not a unanimous view among the Barry board members?

The first time that Perks attended a meeting of the Barry board, on 27 April 1887, was the result of a board decision at the preceding meeting that: “Mr Cory be authorised to offer his friend £300,000 to £400,000 [of the new prefs to be issued] at par …” Perks and John Cory had come to know one another through their shared religious and political affiliations. Both were Wesleyan Methodists. Both were active supporters of the Liberal party, and had remained “Gladstonian” Liberals following the split in the party over Home Rule for Ireland. Lewis Davis was a second Barry director who Perks had come to know before 1887 through those same shared affiliations. Lewis Davis resigned from the Barry board in October 1887 due to illness, and he died on 1 January 1888. His son F.L. Davis took over his Barry board seat, and also took over responsibility for managing the family colliery enterprise that had been established by Lewis Davis’ father. By 1890 this enterprise was producing at a rate of close to 1.1 million tons of coal per year and was the third biggest producer of steam coal in Wales, after the Ocean Coal Co., and Powell Duffryn.[151] In early 1890, F.L. Davis took action to convert the two partnership structures that comprised the enterprise into a limited liability company, and to offer shares and debentures in this new company to the public with a view to giving it a broader shareholder base and to allow for stock exchange trading in its shares, while retaining family control of the enterprise. The promotion and flotation of this new company, “D. Davis and Sons, Ltd, Ferndale Steam Collieries”, was organised for Davis and his family by Perks. Care needs to be taken re the name of this enterprise. It is Davis, not Davies. Its proprietors (see footnote 42) were not the proprietors of the Ocean Collieries enterprise.

This new company was registered on 3 May 1890 by Perks’ legal firm (Fowler, Perks, Hopkinson and Co), the agreements for the terms and conditions of the sale of the various colliery assets into the new entity having been signed-off on in late April.[152] The boom in demand for Welsh steam coal together with the improved facilities for meeting that demand created by the opening of the Barry dock and rail system had enhanced the value of the Davis family enterprise, as compared with the position three years or so earlier. Some of the 24 members of the Davis family among whom the ownership rights were distributed[153] would probably have been keen to see that enhanced value realised (or realisable) into cash. At the same time many “outsiders” to the Davis family would probably have been enthusiastic about the prospect of being able to buy into ownership of a well-established enterprise operating in an industry experiencing booming demand for its product. Under these circumstances, for outside investors optimistic about the future of the Welsh coal industry (and confident about the management of this enterprise) to buy ownership rights from those erstwhile owners worrying about another downturn in coal prices, or simply wanting “to hedge their bets”, would clearly represent a win-win situation. Thus the preconditions for a successful public flotation of the Davis firm were present.

But having the preconditions in place does not guarantee a successful float. The task that Perks took on was that of an intermediary, and to succeed he needed to structure and price the deal in such a way as to satisfy the vendors that they were receiving appropriate recompense for what they were divesting ownership of, whilst simultaneously satisfying a large enough number of subscribers that they were not being asked to pay too much for the paper being offered in the new company. As in many of the financing arrangements designed and managed by Perks, the Davis float contained a novel feature. In this case the novelty was that the capital structure of the new company contained, in addition to £450,000 in £10 ordinary shares, £225,000 in a special type of 5 per cent “debenture bonds” (of £100 each). Dividends on the ords were not to exceed 10 per cent in any year until these debentures had all been redeemed. In a year when the company’s profits were more than sufficient to pay 10 per cent on the ords, the surplus was to be used to redeem randomly selected debentures at £105 per £100 bond (on top of the holders being paid their 5 per cent p.a. interest).

For the assets transferred into the company, the vendors were to be paid a total of £630,000 in a mix of ords, debentures and cash. This would leave £45,000 from the company’s total capital (ords and debentures combined) to be “working capital”. Each of the various Davis family members was allowed an apparently wide degree of choice about the payment mix he or she would receive. Many must have been attracted by the debentures. A safe 5 per cent p.a. was a good rate of return in 1890. And here there was the prospect of a 5 per cent “bonus” as well. The Davis family members took almost all of the debenture issue as part of their vendor consideration: £210,000, leaving only £15,000 for public subscribers ─ although this was not spelt out in the public prospectus published on 3 May 1890.[154] This meant that it was not necessary to allot as many ords to the public in order to raise the cash needed for the cash element of the vendor consideration. And this in turn meant that the original owners of the enterprise were able to continue to hold 60 per cent of the ords, whilst receiving 57 per cent of their vendor consideration in the low-risk form of cash and debentures. By the time Perks arranged an application to the London stock exchange for a Special Settlement Day (SSD) for the company’s ords in March 1893, £140,000 out of the £225,000 of debentures had been redeemed through “drawings”, with payment of the five per cent “bonus”.[155]

The prospectus for the D. Davis and Sons company appears to have been very well received among the investing public. In his chapter on “Capital Formation” in the South Wales steam coal industry to 1914, R.H. Walters examined public issues of shares in “long established family concerns hitherto inaccessible to the investing public.” He stated:

The greatest flotation of this kind was that of D. Davis and Co. Ltd in 1890 whereby £179,700 was raised in £10 shares as part of the cash payment due to the partners of the firm of David Davis and Sons. These were vastly over applied for, preference being given to customers who were thought to have been the only allottees, and were rapidly dealt in at a premium.[156]

The market price of the shares seems to have moved rapidly to the band of £12 to £12.5 per £10 share and to have then remained in that band for the next three years before moving higher.[157] But the firm’s coal customers do not seem to have been the only allottees. Barker and Mewburn, the Manchester stockbroking firm, was allotted 500 of the £10 shares. This would have been in connection with Barker and Mewburn having agreed to be one of the brokers cited in the company’s prospectus, along with W.H.L. Barnett and Co., of the London stock exchange, and five “local” stockbroking firms based in Cardiff and Bristol. The fee for Perks’ services in the float process was one per cent of the £630,000 total vendor consideration, and was paid by the vendors rather than by the new company itself. Perks used this fee to subscribe successfully for 630 of the company’s shares, becoming the company’s tenth biggest shareholder according to its 23 July 1890 shareholders list.[158] Perks’ cousin S.H. Perks was one of the fortunate subscribers to receive an allotment, 300 in his case. Retired and living in Chislehurst, he is unlikely to have been a significant customer for the firm’s product. Whereas both Perks and his two brothers-in-law sold their entire holdings soon after the successful float, S.H. Perks continued to hold most (250) of his shares in the Davis company into the early 1900s.[159]

During the next twelve months Perks organised the flotation of two further South Wales colliery enterprises: “The Penrikyber Navigation Colliery Company Limited”, and “The Albion Steam Coal Company Limited.” Both of these companies were registered by Perks’ legal firm (on 29 May 1890 and 1 April 1891 respectively).[160] As with D. Davis and Sons, the prospectuses for these two companies cited Perks’ legal firm among the company’s solicitors, and cited W.H.L. Barnett and Co plus Mewburn and Barker alongside local firms in Cardiff and Bristol as brokers to the offers.[161]

The Penrikyber enterprise had been established in 1872 as an 8-member partnership. John Cory and his brother Richard were two of those eight, but their more substantial colliery interests were held through other entities, and they made no attempts at public floats of those interests in the favourable conditions of 1890/1891.[162] So it is not clear where the impetus for the Penrikyber float came from. The driving force may have been John and Richard Cory’s younger brother Thomas, a partner with them in Penrikyber, but not in their main business activities, as the press sought to make clear when Thomas Cory “suspended payment” in March 1895.[163] Thomas Cory was chairman of the ill-fated National Bank of Wales and was listed as a director in at least four company prospectuses published in the Times during the seventeen months preceding the Penrikyber prospectus (in which he was named as a director).[164] Others among the Penrikyber partners may also have been keen to sell down their interests in the enterprise, and “ambitious” regarding the terms. It seems that in the case of this float Perks found himself unable to contain pressure from such ambitions. The vendor consideration was set at £350,000, more than 55 per cent of the Davis collieries figure for an enterprise with well under 40 per cent of the output.[165] And the capital structure of the arrangement was a fairly standard mix of ordinaries and prefs, with half of the total number of each to be sold to public subscribers to raise the 50 per cent cash component of the overall vendor consideration. Interestingly, the formal agreement establishing the new Penrikyber company contained a clause that was not present in either of Perks’ other two colliery floats, namely:

If the whole of the said preference shares and ordinary shares other than those which the vendors are to be entitled to as aforesaid are not subscribed for on or before allotment the vendors will accept such preference and ordinary shares as shall not have been applied for in full satisfaction and discharge pro tanto of the balance of the purchase money …[166]

The Penrikyber float was not a success. Cash subscribers came forward for only 2,961 prefs and 1,662 ords, out of the 10,000 prefs and 7,500 ords offered. The clause quoted above was triggered and the remaining shares distributed among the vendors in terms of an agreement finalised in August 1890.[167] Neither Perks, nor any of his family members or circle took up any shares in this company.

The float of the Albion Steam Coal Company Limited, in contrast, went much better. The formula Perks was able to employ in this case was the same one that had succeeded in the David Davis and Sons float. The overall capital base of the new company consisted of £220,000 in ordinary shares of £10 each plus £100,000 in 5 per cent “debenture bonds” of £100 each. Dividends on the ords were restricted to a ceiling of 10 per cent in each year until all of the debentures had been redeemed, and all “surplus profits” above that 10 per cent ceiling were to be used to redeem randomly drawn debentures at £105 for each £100 “face value”. The prospectus offer was oversubscribed and “letters of allotment and regret” were posted out to subscribers on 18 April 1891.[168] The company’s first shareholders list, dated 24 July 1891 shows Perks holding 500 of the £10 shares, making him the tenth largest shareholder. His brother-in-law John Lees Barker has 100 and his cousin S.H. Perks 150. As was the case with David Davis and Sons, Perks and his brother-in-law appear to have sold fairly soon after the float, while S.H. Perks retained his shareholding until the end of the century.[169]

The subsequent dividend record of the Albion company indicates that the overall vendor consideration paid for the colliery enterprise sold into the company (£310,000) had been a “restrained” figure rather than an “ambitious” one. For each year 1891 to 1895, a dividend of 10 per cent was paid, and the £100,000 debenture issue was fully redeemed by the end of 1900, with payment of the £5 per £100 “bonus”. Penrikyber, in contrast, after a good initial year (10 per cent on it ords for 1890) paid no more than 6 per cent in any year from then until the boom year of 1900.[170] The partners who had sunk the Albion collieries in the 1880s and who employed Perks to manage the flotation of their enterprise in 1891 were not board members of the Barry company. But the fact that they chose Perks and agreed to the same float structure as he had used eleven months earlier for the Davis family’s enterprise suggests a perception that the Davis family had been served well by Perks’ management of their float.

It would seem reasonable therefore to conclude that F.L. Davis can be identified as one member of the Barry board who maintained good business relations with Perks during the 1890 to 1892 period ─ notwithstanding the reaction of some of the other Barry directors to Perks’ role re the Walker claims against the company. It seems likely that the same applies to John Cory, even though the Penrikyber float was not a success. Cory joined with Perks and fellow Wesleyan Methodist Thomas Owen (1840-1898) to form a new limited liability company in March 1892 to take over ownership of Owen’s Ely Paper Works in Cardiff.[171] And further into the 1890s both Cory and F.L. Davis joined a syndicate organised by Perks to inject capital into the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway.[172]

The construction of the Barry dock and rail system and its commencement of operations allowed substantially increased quantities of South Wales coal to be conveyed in a cost-efficient manner from the valleys to the holds of awaiting ships. Some 3.2 million tons of coal were loaded and shipped from Barry in its first full calendar year of operation, 1890. In 1892 the figure was 4.2 million tons.[173] As has already been noted in Section I, the Taff Vale Railway (TVR) (with financial assistance from the Bute docks) cut its charges for carrying coal immediately the Barry system opened. The Economist reported that the TVR notice was circulated on a Saturday and that on the following Monday the Barry company sent out a circular stating that “the rates in respect of this [coal] traffic to and from Barry dock will in no case be higher than the corresponding rate for like traffic to and from any dock at Cardiff or Penarth.”[174] Thus the creation of the Barry enterprise added value to the collieries served (or even merely potentially served) by the Barry’s rail and port system. Perks’ two successful colliery floats of 1890-1891 can be thought of as a means of capitalising on some of that “added value” generated by the Barry system (enhanced by the continuing buoyant demand for South Wales coal).

(R J Rimell (1923) History of the Barry Railway Company 1884-1921)

This was not the only avenue through which Perks used his skills to “unlock” some of the “external benefits” generated by the Barry company. In April 1889, Perks registered a new company of a quite different nature from that of the three colliery companies of 1890-1891. This company had a much smaller authorised share capital (£50,000, all in £10 ordinary shares). No invitation to the public was ever made to subscribe for these shares. And Perks maintained his direct interest over a much longer period. This company was titled “The Barry Estate Company, Limited”. Perks was one of its initial directors, alongside T.A. Walker, John Cory and two others.[175] The Financial Times obituary on Perks in 1934 stated: “His sole company interest at the time of his death was the chairmanship of the Barry Estate Company.”[176]

The Barry Estate Company was dissolved in the late 1950s and no records have survived via the BT 31 series at the National Archives. But some information is available from the documents regarding the 1894 Walker Estate Act, and via the records of a successor entity “Barry Estate Holdings Ltd” registered in May 1957. The Barry Estates company was a property development and management enterprise and had taken over business activities which T.A. Walker had already commenced before April 1889. In 1894 the company’s assets were described as:

20 acres of freehold land and 54 acres of leasehold land … close to the terminus of the Barry railway with a long frontage to the property of the Barry railway … [on which have been erected] 80 shops and 470 houses and other buildings … gross annual rent on average for the three years to 30 June 1893 was £8,320.[177]

The first phase of house-building appears to have occurred soon after Walker commenced work on the construction of Barry Dock, and its purpose was to provide some of the accommodation needed for those employed on the dock construction project. When Walker had worked on the construction of the Severn Tunnel, he had built 126 houses and buildings at Sudbrook for equivalent purposes, and still owned those at the time of his death.[178] Tom Clemett has written regarding this first phase at Barry: “It was known as ‘Walkers Town’, and is now High Street and the surrounding streets. It consisted of over 300 properties including shops and other business premises.”[179] According to Clemett, it was not until 1889 that the second block of land (the 54 acres) was obtained in West Barry, and Walker did this in conjunction with the syndicate that then formed the Barry Estate Company.[180] Walker held the great bulk of the shares in this company, with his syndicate-partners contributing debenture finance to meet the costs of additional building and development work. After Walker died it was his executors who held the great bulk of shares and managed the company. Perks, in the dual role of coordinator of the syndicate and legal and financial adviser to the Walker executors was probably “the key man” in the Barry Estate Company from an early stage, although it is not clear when he formally became its chairman.

By 1894 this company was a substantial enterprise with a capital base of over £100,000 (£59,860 in share capital plus £50,000 in 4½ per cent debentures[181]). The census figures for the population of Barry are 85 for 1881; 12,685 for 1891; and 38,000 for 1911.[182] Whereas upon completion of the Severn Tunnel, Walker’s houses in Sudbrook became something of a “stranded asset”, as the Barry dock approached completion the position was quite different. The houses (and associated amenities) Walker built at Barry during the early stages of the work on the dock and railway project could be expected to have their value enhanced by the dock and railway system going into full operation. Perks helped Walker (and after Walker’s death, the Walker Estate) capitalise on this by organising funds to secure additional land and carry out further building of houses and shops etc. Before Walker died, work was also started on building a large and imposing hotel in the centre of Barry. About £12,000 was spent on this project before Walker’s death, and a further £2,000 by his executors afterwards to complete “The Barry Hotel”. It was let by the Walker estate to “substantial tenants” at a rent of £750 p.a. rising to £1,500 p.a. across the 21 years of the lease. For reasons unknown, this hotel development was kept separate from the Barry Estate company.[183]

Perks had previous experience in property development projects of these types, before joining with Walker in these enterprises at Barry. Crane’s 1909 biography of Perks dates his activities in residential property in London back to the mid 1870s stating

[when] some of the large estates which are now covered with thriving metropolitan suburbs were only just beginning to be laid out for building purposes, Sir Robert … interested himself to advantage in some of the more promising schemes.[184]

One of Perks’ earliest company flotations was The Manchester Hotel Company (Limited) in June/July 1879. The purpose of this new company was to acquire and conduct “a commercial hotel in the business centre of the City of London.” The prospectus described the hotel as under construction and “almost completed.”[185] Perks did not himself take up shares in this company but his cousin John Hartley Perks (brother of S.H. Perks) became the third largest shareholder.[186] In 1889 Perks managed the public flotation of another hotel enterprise, this time in a seaside resort in Kent, and this time taking up shares himself to become the company’s fourth largest shareholder.[187] It is possible that the Barry Hotel was kept separate from the Barry Estate Company because initially there had been a plan for a public float of that hotel.

Through the Barry Hotel and the Barry Estate Company, Perks maintained a connection with Barry, and therefore with the fortunes of the Barry Dock and Railway enterprise, beyond the time of his resignation from the board of the latter company in 1890, and beyond the time of the conclusion of the arbitration process re the “Walker claims” against that company in 1892. From the records of the Barry Estate company’s successor entity, it would seem that at some stage the shareownership of the predecessor company had settled into a situation of the Walker heirs owning approximately 60 per cent, and Perks approximately 40 per cent.[188] Perks’ role in these property development ventures may have served to exacerbate the poor state of relations between Perks and the majority group on the Barry board during the 1890 to 1892 period. One of the counter-claims the Barry company made against the Walker executors appears to have been related to the costs of conveying “building materials etc.” from the GWR junction along the Barry company’s railway to Barry, during the period before the opening of the Barry railway for commercial traffic (i.e., when it was under the contractor’s control). The arbitration hearings were held “with closed doors” and the newspaper reports are sketchy. But if the Barry board were accusing Walker of not making appropriate payments for the costs of transporting inputs for his property development venture into Barry, this would no doubt have added to the tensions between Perks and the majority grouping on the Barry board.[189]

Notes and references

[114] RAIL 23/4. Forrest’s name had been listed among the promoters of the company in the 1883 and 1884 Bills (see Rimell op. cit., pp. 21-23). At the same board meeting the vacancy caused by Davies’ death on 20 July was filled by Thomas Webb, a close business associate of Davies since the 1850s, and a director of the Ocean Coal Company Ltd from its formation. (Investors Guardian, 9 April 1887, p. 284).

[115] Charles Hay Walker, Louis Philip Nott, and Thomas James Reeves. C.H. Walker was the son of T.A. Walker’s brother and partner Charles, who died in 1874. He was Walker’s chief agent on the Barry docks contract from 1884 to 1887, after which he took charge of the Buenos Aires project. He was married to one of Walker’s four daughters. Nott was also a son-in-law of Walker’s. He supervised work on the Preston docks project and on two sections of the Manchester Ship Canal. T.J. Reeves was not a family member, but a long-serving employee who by 1889 was managing the office operations of the Walker organisation.

[116] Frederick Lewis Davis (1863-1920), was the only son of Lewis Davis. He replaced his father on the Barry board in October 1887. Lord Windsor was from that point no longer the youngest member of the board.

[117] Lancashire Record Office, Preston. CBP 60/19/1. Letter dated 8 October 1886, in bundle titled “Copy Correspondence between the Contractor and the Corporation”. Later in October the Corporation expressed confidence in Garlick. But in July 1887 Garlick’s resignation was accepted. The 1889 Board of Trade Commission arrived at essentially the same conclusion as Walker had on the need for the channel dredging to be synchronised with the completion of the dock (and its opening to the Ribble). Wolfe Barry was one of the three members of that Board of Trade Commission.

[118] The Law Times, vol. 36, 1877, pp. 53-58 (“Walker and Another v. London and North Western Railway Company”).

[119] Times, 19 December 1876, p. 10 and 30 January 1877, p. 10.

[120] T.A. Walker’s brother Charles died on 30 December 1874, aged 44, one year into the three years of litigation with LNWR. His estate was sworn at “under £6,000: No Leaseholds”. He may not have had as great as a half share in the “contractor for public works” partnership with his brother. Nevertheless, this figure suggests that the assets of the Walker enterprise were at this stage extremely modest compared with their scale by the time of T.A. Walker’s death.

[121] The outline of this agreement is at pp. 236-7 of RAIL 23/2. It includes, as point 6, that Wolfe Barry be the sole arbitrator and that Walker was not to appeal or have recourse to any Court of Law regarding the result of such an arbitration.

[122] Minutes of Proceedings of I.C.E., volume C (1890), pp. 418-419 (unsigned).

[123] John Franch, op. cit., p. 316.

[124] ibid., p. 317.

[125] Minutes of Proceedings of I.C.E., volume c (1890), p. 418.

[126] For example: R.S. Joby, The Railway Builders: Lives and Works of Victorian Railway Contractors, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1983, p. 156.

[127] TNA RAIL 23/2 p. 362. Walker complains that he “and his family” had been excluded on the day.

[128] Engineering, 29 November 1889, pp. 635-6; and The Engineer, 29 November, 1889, p. 450.

[129] Railway Times, 7 September 1889, pp. 299-300. (Report of meeting held 30 August).

[130] TNA RAIL 23/2.

[131] ibid., p. 403. At the 6 December 1889 board meeting: “The Secretary was instructed to write a letter of condolence to Mrs Walker and her family …”, and at the 17 January 1890 meeting, Mrs Walker’s letter of thanks for this “was read”.

[132] ibid. The board resolved to seek the AG’s opinion on the matter.

[133] TNA RAIL 23/4 (“Directors Minute Book No. 2, 21 March 1890 ─ 7 June 1895”).

[134] The Barry company kept a collection of press-cuttings, pasted into bound volumes. Copies of these SWDN articles are in that collection: See TNA RAIL 23/34, pp. 42-43.

[135] Engineering, volume 49, 6 June 1890, p. 676.

[136] TNA RAIL 23/24, p. 43.

[137] This was reported in Engineering, volume 53, 18 March 1892, p. 348.

[138] TNA RAIL 23/4.

[139] ibid.

[140] TNA RAIL 23/34, p. 94. A second article reports the Barry directors complaining that Perks’ letter to the press in June, providing details of the executors’ claim, was “issued through the press before it was in the hands of the secretary of the company” (ibid, p. 95).

[141] Ibid, p. 197

[142] Reported at the Barry board meeting of 8 April 1892. TNA RAIL 23/4. All later references in the board minutes to the Walker arbitration concern the issue of Robinson and Downing’s “extra services”.

[143] See House of Lords Records Office, HL/PO/JO/10/9/1349.

[144] ibid.

[145] For more on the November settlement see Ian Harford op. cit., p. 147 and p. 166 (footnote 50). The existence of the settlement was not made public until the company’s half-yearly report was distributed to shareholders shortly before the 3 February 1891 meeting.

[146] Times, Wednesday 4 February 1891, p. 12.

[147] Financial Times, 4 February 1891, p. 2.

[148] R.W. Perks, op. cit., pp. 105-6.

[149] Edgar Jones (ed.), The Memoirs of Edwin Waterhouse: A Founder of Price Waterhouse, Batsford, London, p. 160. On Waterhouse, see J.R. Edwards entry on him in volume 5 (pp. 674-679) of David J. Jeremy (ed.), op. cit.

[150] Engineering, 29 November 1889, p. 636. The third edition of Walker’s 1888 book The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties 1872-1887, contains a 5 page introductory note by John Hawkshaw, written in June 1890. In this, Hawkshaw makes similar comments on the way Walker operated saying it “brought upon him an immense amount of labour over and above that which must necessarily fall to the lot of a large contractor, and it probably tended to shorten his life.”

[151] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 273. None of Powell Duffryn’s owners were members of the Barry board. The five enterprises with output above one million tons per year accounted for 35 per cent of total South Wales production in 1890. The next eight biggest (with over half a million tons each) accounted for a further 29.2 per cent (ibid., p. 271-274).

[152] TNA BT 31/31205/31383.

[153] The ownership rights were not confined to the heirs of Lewis Davis and his brother David Davis junior. Three of their five sisters had had children, and these also had inherited rights in the family enterprise. In addition to the 24 Davis family members, there were three members of the Warner family with a minority holding in the smaller of the two partnerships. One of these Warners became a director of the new company.

[154] Financial Times, 3 May 1890, p. 5 (and repeated 5 May, p. 6 and 6 May p. 6). Times, 3 may 1890, p. 8; 5 May, p. 3 and 6 May 1890, p. 13. The three Warners took ords only as their vendor consideration, which totalled £38,000.

[155] Guildhall Library: Manuscript 18,000: 33B/238. (An SSD was approved for Tuesday, 30 May 1893).

[156] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 122.

[157] Guildhall Library: MS 18,000: 33B/238. The London Stock Exchange Yearbook for 1894 cites “the latest price” as £13 (p. 668) and the following year £13½ (p. 687).

[158] TNA BT 31/31205/31383.

[159] ibid.

[160] Financial Times, 6 June 1890, p. 6 and 8 April 1891, p. 3.

[161] Times, 29 May 1890, p. 14 and 7 April 1891, p. 14.

[162] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 142 and pp. 118-119.

[163] Times, 23 March 1895, p. 2. Under the headline “Failure in Wales”, the report states: “He is brother to John and Richard Cory of Cory Bros and Co (Ltd) Cardiff. He has no connexion with that firm but is a director of …”

[164] Wingello Coal Company Ltd (Times, 13 January 1888, p. 14); Cheadle Railway Mineral and Land Co. Ltd (Times, 18 January 1888, p. 13); Buenos Aires New Tramways Co. Ltd (Times, 26 October 1888, p. 15); The Randt Coal Mining and Land Co. Ltd (Times, 8 March 1889, p. 14). After the National Bank of Wales merged with a larger bank in 1893, it was discovered that its accounts had been misrepresented for several years. A transaction from December 1890 led to Thomas Cory being sentenced to 8 months hard labour in February 1898. (See Times, 8 February 1898, p. 9.)

[165] The Stock Exchange Yearbook for 1891 cited Penrikyber’s output level at the time of the float as “nearly 400,000 tons p.a.” (p. 578).

[166] Companies House, Cardiff, file on company number 31556. The final name of the Penrikyber company, at the time it was dissolved in 1995 was “Chapman Hall Gray Limited”.

[167] ibid.

[168] Times, 4 April 1891, p. 11; 7 April 1891, p. 14; and 18 April 1891, p. 13. The company’s authorised share capital was £250,000, but the £30,000 of this that was held back from being “created” in 1891 was never in fact issued, and was eventually “extinguished” in 1901. See TNA BT 31/31242/33695.

[169] TNA BT 31/31242/33695.

[170] R.H. Walters, op. cit., p. 293; and Walter R. Skinner, The Mining Manual, 1903, p. 866.

[171] See O. Covick op. cit., pp. 20-21.

[172] ibid, p. 24-26.

[173] Ivor Thomas op. cit., p. 306. Hood told the February 1891 shareholders meeting that the directors were expecting to exceed 5 million tons per year “soon” (Times, 23 February 1891, p. 3) but that figure was not reached until 1895.

[174] Economist, 14 September 1889, pp. 1171-72, “A Welsh War on Rates.” In January 1890, the Times published a letter from G.C. Downing stating that the Barry company had not initiated a “rates-war” with the TVR but had been “obliged in self-defence to follow.” (2 January 1890, p. 9).

[175] Financial Times, 27 April 1889, p. 4. The two other initial directors were A. McNab and L.W. Williams. Lewis Williams of Cae Coed, Cardiff, was owner of the foreshore rights at Barry (Rimell, op. cit., p. 19).

[176] Financial Times, 1 December 1934, p. 6.

[177] H.L.R.O. HL/PO/JO/10/9/1457, Bill 187.

[178] ibid.

[179] Tom Clemett’s History of Barry website (www.barrywales.co.uk) viewed 26 September 2007, p. 6 of section “Town Builders and Developers.”

[180] loc. cit.

[181] HLRO HL/PO/JO/10/9/1457, Bill 187. The Walker trustees held 5,766 out of the 5,986 ordinary £10 shares (all fully paid) issued by the company, but none of the debentures. It is not clear when the company’s authorised capital was increased from its initial £50,000. In 1953 the figure was £70,000 (Times, 3 December, 1953, p. 14 has a legal notice re. a reduction from that figure by a £7,000 return of capital to shareholders).

[182] Cited at p. 344 of Trevor Boyns and Colin Baber, “The Supply of Labour, 1750-1914”, in volume 5 of Glamorgan County History (edited by Arthur H. John and Glanmor Williams).

[183] HLRO HL/PO/JO/10/9/1349, paper number 379. Evidence for regarding the Sudbrook houses as a “stranded asset” comes from the statement in the 1894 Walker Estate Bill that if the Trustees were given power to continue operating Walker’s shipyard at Sudbrook this would “then keep these houses occupied as well.” (HRLO HL/PO/JO/10/9/1457, Bill 187).

[184] Denis Crane, op. cit., p. 62.

[185] Prospectus published in Times, Wednesday 23 July 1879, p. 13. The company was registered by Fowler and Perks, on 14 June 1879 (TNA, BT 31/2536/13150). The hotel was at 117 to 121 Aldersgate Street.

[186] TNA BT 31/2536/13150. J.H. Perks held shares in the company through until 1907.

[187] The Littlestone Hotel Company Limited, registered 4 October 1889 (Financial Times, 11 October 1889, p. 4). See Owen Covick op. cit., pp. 32-33.

[188] “Barry Estate Holdings Ltd” was dissolved in 1986 but the microfiches of its filings with Companies House are still available in Cardiff (Company number 00583579). When this company was formed in 1957 its shares were distributed pro rata to shareholders in the antecedent company. The figures cited are for the “split” between T.A. Walker family members and R.W Perks family members. Holdings by “others than those” were negligible.

[189] TNA RAIL 23/24, pp. 96-97.