This article reproduced with kind permission from The Railway & Canal Historical Society.

Click the yellow journal cover image to access the full journal directly from their archive.

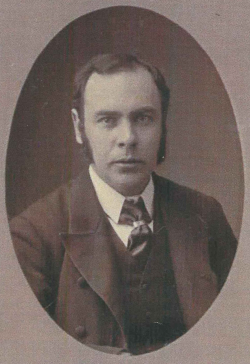

The length of time R.W. Perks was a director of the Barry Railway Company scarcely exceeded three years, and the period during which he was regularly attending board meetings was shorter still, at less than two years. But those two years were highly significant in the history of the Barry enterprise. The contribution made by Perks during that period was important in shaping the Barry business for its later highly-prosperous performance. And Perks’ role in that formative period of the Barry enterprise was important in shaping Perks’ subsequent business reputation and business career.

Section I of this paper explained how the Barry company had come to be encountering severe financial stress by the end of 1886/beginning of 1887. The company had commenced construction of its integrated dock and rail system with a narrow shareholder base dominated by a small number of colliery proprietors and coal shippers (and their business associates) who would be the principal customers for the enterprise’s services once its infrastructure had been completed and came into operation. For those of the company’s shareholders (and potential shareholders) who were not going to be customers for its coal carrying services, this meant facing a risk over and above that of whether there would be enough ongoing demand for South Wales coal to justify the building of the new facilities, and whether costs of construction could be kept within reasonable dimensions of time and money. In addition there was the risk that if completed at reasonable cost and operating at reasonable capacity, too much of the value created by the Barry port and rail system would “disappear” into low prices for the customers and not enough retained to provide satisfactory dividends for the Barry shareholders. For as long as the Barry company’s narrow shareholder base of colliery proprietors and coal-shippers were themselves willing and able to furnish whatever additional share capital was required to fund the enterprise’s construction programme, this “worry” for outsider shareholders was not a problem for the company as a whole. But once it became clear that the original core shareholders would not be able to satisfy the company’s needs for additional share capital, tension emerged. Could outsider share capital be attracted into the company on the scale required, without the terms and conditions required for this jeopardising the future internal dynamics and managerial stability of the Barry enterprise?

By the opening months of 1887, it seems to have been accepted by the Barry board that no realistic alternative was available but to attract some substantial new outsider-investors into the company. Without this it would not be possible to provide all the additional capital necessary to complete the dock and rail system on something like the original timetable.

Through Perks, these challenges to the Barry company were tackled, as was explained in Section II. Perks organised the “rescue party” of new outside contributors of capital funds. He organised the mechanisms through which this “rescue” was delivered ─ including helping David Davies secure personal loan funds to enable him to put more share capital into the company himself. At the same time, Perks smoothed the way for the Barry company’s principal contractor, T.A. Walker to press forward to a timely and high-quality completion of the construction work, undistracted by fears as to whether the company would be able to pay his bills. Having Perks as a director represented a degree of “power-sharing” on the part of the original core-shareholders in the Barry company. As well as being a condition for the “rescue”, this no doubt facilitated the delivery of that “rescue”.

Because of the successful performance of the Barry company during this “power-sharing” period, and because an upsurge in the demand for South Wales coal improved the economic fundamentals of both the Barry company and its colliery-owner/coal-shipper core shareholders, Perks had ceased to be indispensable to those original core shareholders by mid 1890. And at this same time, tensions emerged between the majority group on the Barry board and Perks regarding claims made against the company by T.A. Walker’s executors for further payments in respect of Walker’s contracts. Perks thus departed from the Barry board under less than amicable circumstances in mid-1890, and the tensions continued until the formal arbitration process over the Walker executors’ claims reached its conclusion in April 1892. This was the subject matter of Section III of the paper ─ which in addition discussed the “good” business relationships that were maintained between Perks and some of the Barry directors during this period.

Once Perks’ involvement with the Barry company’s affairs had ended, and the enterprise’s original core-shareholders were comfortable in enjoying restored full control, it was probably convenient for many of them to “paper-over” the financial stresses the company had experienced during 1886 to 1888, and to paint Perks out of any substantial role in the company’s self-image of its history. At the same time it may have become convenient for Perks to downplay the fact that his first directorship of a significant public company had been his three years on the Barry board, commenced at a youthful 37 years of age. To draw attention to that role might simply have provoked questions about the circumstances under which he had departed from it. During Perks’ subsequent business career, it was often useful to him that people knew he had organised a syndicate to help fund the highly successful Barry Railway enterprise ─ but why overload people with extraneous detail? Thus, when Perks gave evidence before the House of Lords committee on the Llanelly Harbour and Portdulias Railway Bill in May 1899, he was asked:

Q: … you have very large experience in the placing of the issues made by various railway companies in South Wales and elsewhere?

A: Yes, I have had a great deal of experience … I had a great deal to do with the letting of the stock of the Barry Railway in its early inception when it was refused in London, and my friends and I took a very large quantity of stock at par, which went to a very large premium.[190]

The level of detail about Perks’ contribution to the Barry enterprise in this evidence is about the same as that presented in Perks’ own Notes for an Autobiography, and in neither case is any mention made of Perks having been a director of the Barry company. Crane’s 1909 biography of Perks devotes only one paragraph to the Barry enterprise, is silent re. the board seat, but fairly explicit that Perks’ role was largely concerned with the successful financing of the project.[191] But on those occasions when Perks was asked to provide information about his business career subject to a tighter “word-limit” and for broader audiences, he seems to have preferred to downplay his skills as an organiser of the financing for the various public works projects he worked on, and to leave the nature of his contribution(s) to those projects somewhat ambiguous. Perks was elected to the House of Commons in July 1892. During his first two years as an MP, his entries in Dod’s Parliamentary Companion made no mention of the Barry enterprise, but from 1894 each year’s entry included the words:

was associated with the late T.A. Walker in the construction of the Barry Docks and railways, Preston Docks, Manchester Ship Canal, and the Buenos Ayres Harbour Works.[192]

When Who’s Who commenced the format we now associate with the title, this same wording was carried across into Perks’ entry, except that “interested” was substituted for “associated” ─ until 1913 when it reverted to “associated”. Thus Perks’ own account of his contribution to the Barry company during its phase of financial stress in 1887-89 was not publicly advertised. Rather, Perks seems to have held that detail back for consumption by the more financially-sophisticated, and hence better-equipped to appreciate it. For those consumers of information on public works projects who believe the question “who built it?” should always take paramountcy over the question “who found the money to build it?”, Perks seems to have been happy not to argue, but simply to assert his association with Walker. Clearly, in the absence of people with these “lower-profile” skills in the field of financial organisation, as displayed by R.W. Perks in the case of the Barry Railway, the “high-profile” builders of public works projects would not have had the opportunity to display their prowess in the way enjoyed by T.A. Walker.

Afterword

While Wolfe Barry’s formal arbitration of the Walker executors’ claims against the Barry company was still in progress, the Barry board advertised for tenders for the construction of “a lock 600 feet by 65 feet, adjoining the existing entrance and basin of Barry Dock.”[193] On 27 November 1891, this contract was let for £152,938 7s 6d to John Jackson, who had “almost” been awarded the original dock contract in 1884 (see Section I). Patricia Spencer Silver’s recent biography of Jackson describes how a dispute over “extras” emerged between Jackson and the Barry company on this contract, and how Jackson took legal action to try to prevent Wolfe Barry acting as sole and final arbitrator over the dispute.[194] Jackson won the first round of this legal battle but his injunction was over-turned on appeal. Jackson’s pursuit of his claims for extras on the lock contract did not prevent the Barry board from awarding him a further contract for £309,000 to construct additional extensions to the dock facilities commencing in January 1893.[195] Thirty years later, in 1926, control of the John Jackson enterprise passed from Jackson’s heirs to a group which included Perks’ son Robert Malcolm Mewburn Perks, born in July 1892. R.M.M. Perks became a director of Sir John Jackson Ltd under these arrangements, and then chairman of the company through the 1930s and into the late 1940s.[196] Thus a further connection between the Perks family and the building of the Barry enterprise came latterly into being.[197]

Notes and references

[190] TNA RAIL 1066/1531, Questions 986 and 988.

[191] Crane op. cit., p. 76. Neither Crane nor Notes for an Autobiography make any mention of the three colliery company flotations or of the Barry Estate enterprise, or the Barry Hotel.

[192] Dod’s Parliamentary Companion, 1894, p. 321.

[193] Times, 2 October 1891, p. 2. (Tenders were to be lodged by 14 November 1891).

[194] P. Spencer-Silver, op. cit., pp. 65-66.

[195] loc. cit.

[196] Companies House, Cardiff, file on company number 58584, Sir John Jackson Limited. Jackson’s nephew Arthur Jackson remained on the board of the company following the 1926 changes but with all three of the other board seats going to the “new” interests.

[197] Two further members of the Perks family served periods as directors of the John Jackson company during the 1930s: Norman Perks Volckman (a nephew of R.W. Perks) and Bertram Cowles Allen (who had married one of Perks’ daughters in 1908).